View the Global Employability University Ranking 2015 top 150 results

Universities’ frequent claims to prioritise the creation of work-ready graduates can come across as hollow clichés, with little material impact on what they actually deliver to students. But the National University of Singapore’s leap up a global ranking for employability, published today in Times Higher Education, suggests that its own efforts are having a significant effect.

Every year, 200 of its most entrepreneurial students are chosen to spend six months or a year abroad. Selecting from Silicon Valley, New York, Stockholm, Beijing, Shanghai or Israel, they work at a small start-up company in the day and attend classes in technology entrepreneurship in the evening. Upon their return to the NUS, they are housed in an entrepreneurial-themed campus residence and encouraged to share their experiences and to create their own businesses and products. So far, they have founded 350 companies since the programme was launched in 2001.

“Every year, employers look out for these graduates, and they are usually offered much higher salaries [than other graduates],” says Tan Eng Chye, provost and deputy president for academic affairs at the NUS. “The nice thing is many of them become mentors to junior students here and add to the ecosystem.”

While he is pleased that those selected students do so well, Tan is also keen that the NUS’ work around graduate employability is not limited to a privileged few. To that end, the university is preparing to launch a mandatory programme of workshops, coaching sessions and psychological testing for all first- and second-year students, aimed at enhancing their intrapersonal (“being self-aware and mindful”) and interpersonal (“working in a team, communicating with others and conveying ideas”) skills. Students’ academic, personal and extracurricular achievements will be captured in an e‑portfolio, which they will be able to share with prospective employers.

“Knowledge can become obsolete overnight,” Tan says. “It is important to prepare our students to be agile and adaptable, with the right mindset of lifelong learning.”

The results of the sixth annual Global Employability University Survey suggest that the NUS’ efforts are paying off: employers rate its graduates the 17th most employable in the world, up from 39th place last year.

The survey was designed and commissioned by Emerging, a French human resources consultancy, and carried out by Trendence, a German market research firm. It asks recruiters from 21 major countries for higher education to answer questions about the ideal attributes of graduates and universities, and also to select which institutions they think produce the best recruits (see methodology box at the end of this article). The upper reaches of the ranking consist of a familiar run of globally renowned Anglo-American institutions, topped by Harvard University and the universities of Cambridge and Oxford. But it is not necessary to read far before encountering names much less familiar to aficionados of global university rankings. These include the Indian Institute of Science (20th), French business school HEC Paris (25th) and private Spanish institution IE University (27th).

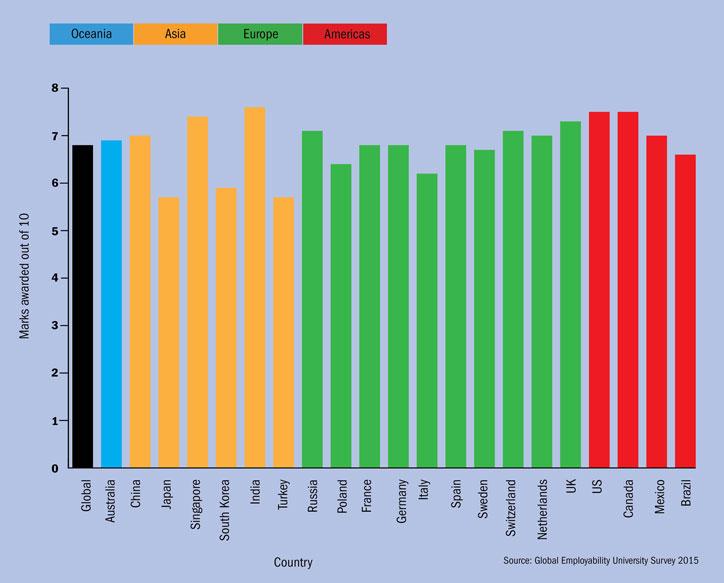

Employers’ satisfaction with higher education in their country

“As recruiters develop a better knowledge and understanding of the global higher education market, reputation plays less of a role and expertise [plays] more,” explains Laurent Dupasquier, associate director of Emerging. “The nationality of young graduates, the country in which they studied and the nationality of the company that employs them is becoming increasingly irrelevant.”

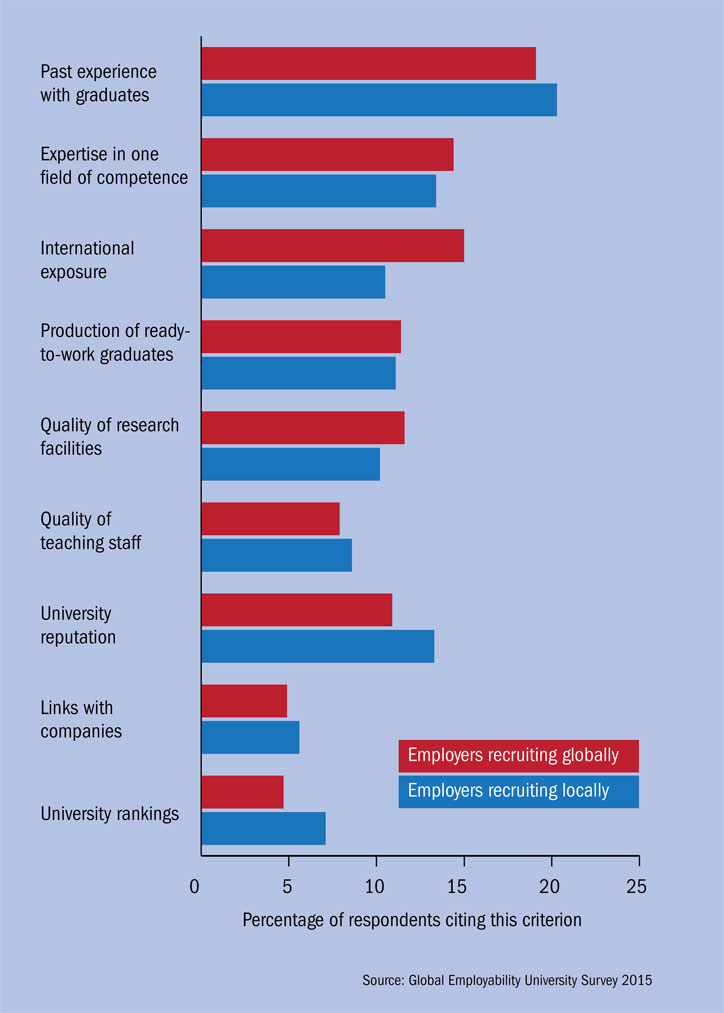

He adds that recruiters across the world generally make the same demands of universities. In every continent, the highest proportion of survey respondents (19 per cent) say that they favour universities based on past experience with their graduates. The second highest proportion (15 per cent) judge according to a university’s international exposure, and the third highest (14 per cent) look for its expertise in the field of competence they are interested in.

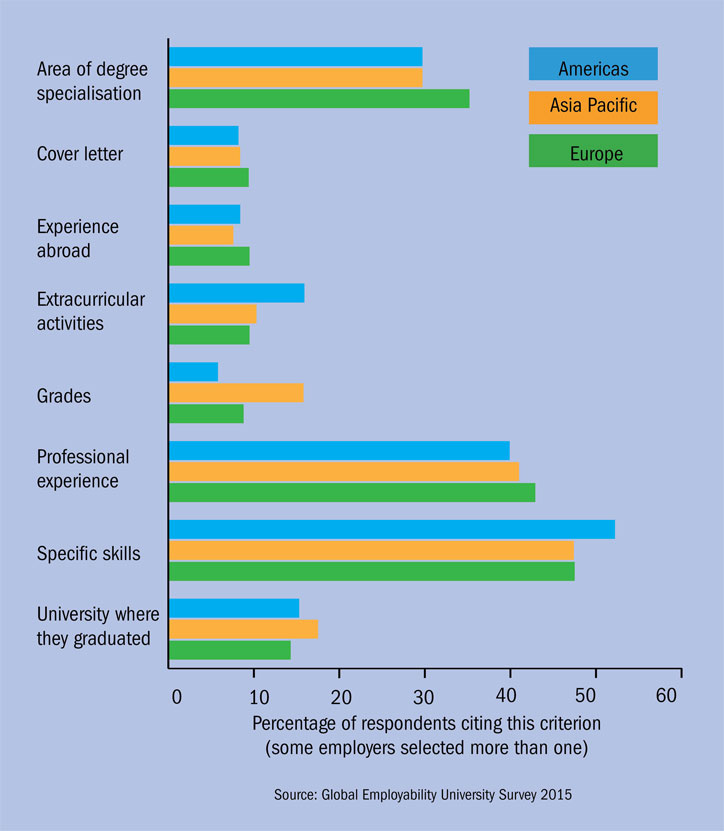

In graduates, employers also want to see the same attributes: in all continents, specific skills are the most important factor, followed by professional experience and area of degree specialisation. On average, grades come bottom of the priority list.

The shift of employers’ focus away from academic qualifications is a trend that has emerged in recent years. Earlier this year, professional services firm Ernst & Young (EY) announced that it would remove degree classification from the entry criteria for its hiring programmes, having found no evidence that success at university is correlated with subsequent success in obtaining professional qualifications. Maggie Stilwell, EY’s managing partner for talent in the UK and Ireland, says that the firm’s new “strengths-based” selection process will focus instead on identifying future potential.

“Some of our best candidates will be those who are able to demonstrate their intellectual capacity alongside strengths such as relationship-building, flexibility and pride in their work,” she says.

The university from which a candidate graduated is only the fourth most important piece of information for employers. However, almost a quarter (24 per cent) of survey respondents say that they employ exclusively graduates from a specific group of universities, while 31 per cent of companies report having a preferred list of institutions from which they typically recruit.

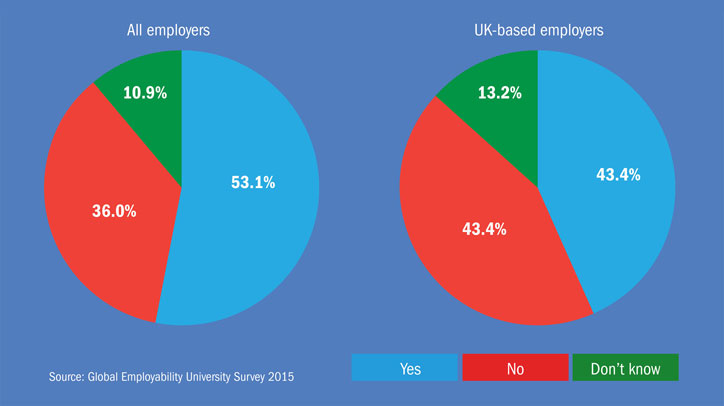

Employers believe that it is important for universities to develop close relationships with them. The majority of respondents (53 per cent) agree with the statement that “only universities able to establish links with companies can promote the employability of their graduates”. David Docherty, chief executive of the UK’s National Centre for Universities and Business, says that higher education institutions have now “woken up” to what he sees as their obligation to help students prepare for careers, and that they accept that work experience “does actually have an impact on what people broadly call employability”. However, he argues, universities still need to be more “sophisticated” and “contemporary” when designing degrees and must move beyond sandwich courses and traditional placements.

Employers’ criteria for selecting graduates

“The irony is that there are more placements being offered by universities than students taking them. Students want a different kind of work experience,” Docherty says. “What we need to do is increase the opportunities for small and mid-sized companies to engage with students. The small company round the corner might be the one that gives [students] the best opportunities.”

Anna Vignoles, professor of education at the University of Cambridge, believes that universities could do more to close the gap between employer demand and graduate supply by using graduate earnings to identify subject areas where more degree courses are needed.

“If students prefer subjects that are not in strong demand in the labour market, you can have a mismatch between what students want to study and what firms need,” she says. “I am not suggesting that employers dictate what students study at university. I am merely saying that with better knowledge about the demand for graduate skills in the labour market, both students and universities can make more informed decisions. Clearly, better communication between employers and universities may also help.”

One institution that has established strong ties with industry and ensures that its staff and students understand which research areas are of interest to businesses is France’s Mines ParisTech. Specialising in engineering, science and mathematics, it is ranked 22nd in the Global Employability University Survey ranking, having climbed 20 places since last year. Its students have to spend at least 560 hours doing internships during their three years of study. They must also carry out class projects in which each student has a role, as they would in a working environment. In addition, they receive individual coaching to help them to decide which jobs to pursue, make applications and prepare for interviews.

Jérôme Adnot, academic dean at Mines ParisTech, adds that half the institution’s annual E60 million (£44 million) research budget comes from contracts with industry. “When students do projects in the lab, they are aware of the present research and development at companies. It means they do not only speak correctly in interviews but they can also integrate relatively easily. Typically, before leaving the school, [each student] receives six [job] offers, and half [of the students] sign their first work contract.”

Mines ParisTech is one of several French institutions to have improved their standings in this year’s ranking. École Normale Supérieure jumps four places to 13th, Engineering school CentraleSupélec (formerly the École Centrale Paris) rises 14 places to 35th and EMLYON (formerly the École de Management de Lyon) is 64th, rising eight places. France has five institutions in the top 50 of the 150-institution ranking – more than any other nation apart from the US and the UK.

Dupasquier says that French institutions appear to punch above their weight in part because of their relatively low scores in other interNational University league tables, which have methodologies that tend to disadvantage specialist institutions. However, he also credits the close links that France’s highly competitive grandes écoles have forged with employers.

Employers’ preferred criterion for selecting which universities to recruit from

Canada is another country that appears to be making strides in employability. It has four universities in the top 50, all of which have risen since last year. Its highest climber is the University of British Columbia, which jumps 16 places to 39th.

According to Dupasquier, part of the reason for Canada’s ascent is a relative downward trend in the US. The University of Arizona, the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Virginia have all fallen out of the top 150 this year, and many other mid-level US institutions have lost ground. Brown University, for instance, plummets this year from 34th to joint 68th, while Northwestern University falls 30 places to 89th. Dupasquier hypothesises that this is a result of the globalisation of education, which means that recruiters and students now place less emphasis on the nationality of a university. In addition, the high cost of tuition in the US may deter highly talented international students.

“If a student wants to go to Harvard, they’ll think it’s extremely expensive, but they’ll definitely pay the money because it’s an investment. The Harvard brand is so strong. But if you want to go to, say, the University of Southern California, it’s not a bad university at all, but it will cost a huge amount of money and not in any way provide a guarantee of a job,” he says.

The highest ranked Canadian institution, the University of Toronto, breaks into the top 10 this year after climbing 14 places since 2012. Cheryl Regehr, vice-president and provost of Toronto, says that the traditional sandwich courses that Toronto offers in disciplines such as engineering result in 70 per cent of participants receiving a job offer during their 12-month placement. But the university also has a range of courses that focus on career readiness. For example, its Faculty of Arts and Science runs a two-day event for undergraduates and recent graduates at which most of the speakers and guests are alumni, and many of them employers: the aim is to help students improve their professional development and build networks with firms. Last year, the same faculty also launched a scheme allowing students to job-shadow alumni mentors in their preferred field.

“What we understood from employers is that skills help students get the initial job, but creativity, critical thinking, analysis and a broad knowledge base contribute to a successful career,” Regehr says. “We want to help students get a sense of how they can take what they learn in the classroom around things like critical thinking and apply it to various settings.”

However, she adds that it is important that universities that score well on graduate employability avoid complacency.

“Great universities are always seeking to do things better,” she says. “Research wants to find better answers to world problems. Our teaching needs to always remain innovative. So the way in which we connect our students with the city, the country and the world, in order to make them great contributors, has to keep adapting as well.”

Decidedly domestic preferences

While there is a general consensus among global recruiters about which criteria are the most important when recruiting graduates, one country bucks the trend: Japan.

According to the findings of the Global Employability University Survey, just 6 per cent of US employers and 9 per cent of European ones rate a graduate’s grades at university as among the most important factor, compared with 16 per cent of those in the whole Asia-Pacific region and 22 per cent in Japan.

Globally, between 71 per cent and 81 per cent of recruiters believe that higher education is a globalised market, but only half of Japanese managers agree. And while most recruiters are generally satisfied with the higher education provision in their country (giving it an average score of 6.8 out of 10), Japanese employers are significantly more critical (giving it an average of 5.7).

Futao Huang, a professor at the Research Institute for Higher Education at Japan’s Hiroshima University, notes that because Japan’s higher education system concentrates funding on a small number of elite universities, students have to work hard to win admission to a top institution but then tend to coast once they get in.

“[In contrast to] the US and some other Western countries, once undergraduate students are accepted…[they] can obtain academic credits and degrees much more easily, without worrying about their grades,” he says.

This is particularly true, he adds, of private universities. These account for more than 70 per cent of the total students and universities in the country, and some of them are already struggling to recruit students as Japan’s population of young people declines.

Another factor, Huang says, is the relatively weak links and poor communication between Japanese universities and employers.

“In a major sense, teaching and learning activities, including curriculum development and assessment…in most Japanese universities are not responsive and relevant to demands from society, and especially from industry,” he says. “In recent years, more and more Japanese companies have made efforts to enhance their international competitiveness by building factories abroad and exporting their products, but they have increasingly realised that a majority of Japanese universities are not able to produce [the skills they need].”

However, Huang points out, the Japanese government has recognised that greater foreign influence could help to redress these failings. In 2012, it launched a national initiative aimed at overcoming the younger generation’s “inward tendency”, with a new funding stream for universities that embrace internationalisation.

Professional finish not required

The Global Employability University Survey highlights “the British paradox”, according to Laurent Dupasquier, associate director of French HR firm Emerging, which designed the survey. UK universities do exceptionally well in the table despite being less focused than overseas rivals on giving their students professional experience – a factor that recruiters consistently cite as one of the most important.

This may partly be explained by the preferences of UK employers. Globally, the majority (53 per cent) of recruiters say that only universities able to establish links with companies can promote employability; in the UK, however, an equal proportion (43 per cent) of employers agree and disagree with that proposition.

Despite this, when recruiters in the UK are asked which criteria they base their university selection on, the most popular response is links with companies, followed by expertise in one field of competence and the production of ready-to-work graduates.

UK employers are still among the most satisfied with their nation’s higher education system (giving it 7.3 out of 10, compared with a global average of 6.8), and the UK has nine universities in the top 50, second only to the US, which has 15. But several UK institutions have dipped in this year’s ranking. While the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford are still in the top three, both have topped the list in previous years. Several London institutions have also slipped: University College London falls 16 places to 30th, for instance, while King’s College London declines eight places to 43rd.

Rob Fryer, head of student recruitment at professional services firm Deloitte, says that UK universities could be doing more to ensure that their students are employable. “Universities are very good at the technical training, but they’re not necessarily training students to apply that within a professional environment,” he says.

Asked which attributes he values in graduates, he says that, like Ernst & Young, Deloitte has moved away from examining “past achievement as a yardstick about what people can do in the future, and started to think about things like resilience, innovation and goal orientation”.

The best institutions he comes across, he says, are those that allow companies to run sessions with their students on how the technical skills they have learned could be applied in the business world.

Employers’ views on whether industry links are a prerequisite for promoting student employability

Global Employability University Ranking: top 10

| Rank | Institution | Country | Score |

| 1 | Harvard University | United States | 662 |

| 2 | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom | 633 |

| 3 | University of Oxford | United Kingdom | 609 |

| 4 | California Institute of Technology (Caltech) | United States | 597 |

| 5 | Yale University | United States | 575 |

| 6 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) | United States | 571 |

| 7 | Stanford University | United States | 552 |

| 8 | Columbia University | United States | 531 |

| 9 | Princeton University | United States | 509 |

| 10 | University of Toronto | Canada | 483 |

View the Global Employability University Ranking 2015 top 150 results

Methodology

The online survey was completed between April and August 2015 by 2,287 recruiters from 21 countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the UK and the US. The countries were chosen on the basis that they are the main global players in higher education, accounting for more than 80 per cent of students worldwide, and have at least one internationally recognised university.

The ranking was created from the combined votes from two “panels”. For one panel, respondents from across the 21 countries were asked to indicate which institutions from a list of their local universities produced the most employable graduates. Companies could cast between three and 15 votes depending on how many of their country’s institutions were entered into the survey; Swiss recruiters, for instance, had just 11 universities to choose from, while US companies had 92. Companies that recruit internationally were also asked to vote for up to 10 universities in the world that, in their experience, produce the most employable graduates.

The second panel consisted of 2,400 managing directors of internationally recruiting companies (or subsidiaries) with more than 1,000 employees. Each cast a maximum of 10 votes for local or global universities. The ranking is based on the total number of votes each institution received.

Companies were also asked a series of questions about the characteristics they value in universities and graduates.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Working classes

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login