Her publisher describes Julia Markus’ Lady Byron and her Daughters as “a startling re-evaluation of Lady Byron’s marriage and the untold story of her complex life as single mother and progressive force”. Untold? Not quite. I count at least four previous biographies devoted to Annabella Byron, another four about her daughter, and several concerning their shared circle. In fact, defences of Lady Byron have emerged periodically since Harriet Beecher Stowe published Lady Byron Vindicated in 1870.

Where Markus is most “startling” is in her condemnation of Byronists such as Malcolm Elwin, Doris Langley Moore and Joan Pierson for failing to be adequately sympathetic to Lady Byron. But a cursory survey suggests that recent scholars have documented her poet-husband’s bad behaviour in far more forensic detail than Markus. Fiona MacCarthy reports that Lady Byron found a copy of the Marquis de Sade’s Justine in her husband’s trunk; Peter Cochran says Byron fired pistols at the ceiling while his wife gave birth in the upstairs room of their Piccadilly house.

Those details – and many others – find no place in Markus’ whirlwind tour of this well-trodden path. It is symptomatic of a larger problem: vagueness. She twice refers to “the freewheeling days of the Regency”, while “the Romantic imagination allowed a poet such as Byron to break though the settled barriers of tradition in order to pierce through to nature – human and divine – in thrilling new ways”. Such generalities curdle into nothingness, such as her claim that the Brownings “created poetry in reaction to the Romantics”.

This penchant for imprecision extends effortlessly to facts: the childhood sexual abuse of Byron by his nurse “is rarely referred to”, she says, quoting Leslie Marchand. But he was writing in the 1950s; subsequent biographers talk about it constantly. Elsewhere, she says that Byron was homosexual, thus avoiding the word “ephebophile”, which is what he was. Conversely, some of Byron’s friends, including William Bankes and John Cam Hobhouse, did have homosexual proclivities, although Markus appears unaware of it. Instead she takes for granted that Medora Leigh was the offspring of Byron’s incestuous union with his half-sister, passing silently over the many arguments against it – including those that fill the pages of G. Wilson Knight’s Lord Byron’s Marriage: The Evidence of Asterisks (1957).

At times, sentimentality gets the better of Markus, bringing with it a rich harvest of falsehood: Lady Byron’s father was “a sweet ineffectual Don Quixote”; Annabella “the Lioness protecting her cub”; Byron “was, as so many of his protagonists – and so many a charming addict – a tortured soul”. This is aggravated by Markus’ desire to “do” her characters in different voices – that is, their inner voices. It doesn’t work, and lapses into nonsense when she appropriates family names such as Hen, Crow and (most outlandishly) Porpoise. When unable to use nicknames, she inserts needless qualifiers: “publisher John Murray”, “friend Charles Dickens”, “socialist Owen”. Not irritated enough? Readers must contend with modern-day Americanisms, applied as if anachronism were no obstacle to understanding: “the real estate market remained stagnant”, Annabella’s mother “acted out emotionally”, Byron “took a swing at a buddy”.

The more successful part of this book addresses the historical period in which Markus is at home – the later 19th century. This may explain why the writing becomes more fluent, but also more perfunctory, as it progresses. Although her affection for such figures as Anna Jameson and the Brownings seems to give Markus confidence, it also prompts her to lose focus; for a while they hog the limelight to the exclusion of all else. Perhaps the real problem is her subject, who she has decided is too immaculate to be other than insipid. Which alerts us to the underlying problem with Lady Byron and her Daughters as a whole: it lacks conviction.

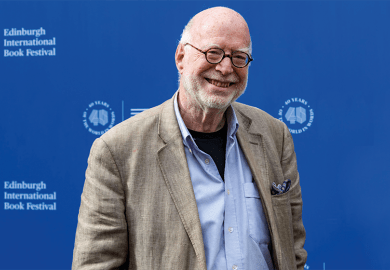

Duncan Wu is professor of English, Georgetown University. He is author, most recently, of 30 Great Myths about the Romantics (2015).

Lady Byron and Her Daughters

By Julia Markus

W. W. Norton, 384pp, £18.99

ISBN 9780393082685

Published 13 October 2015

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login