Source: Getty

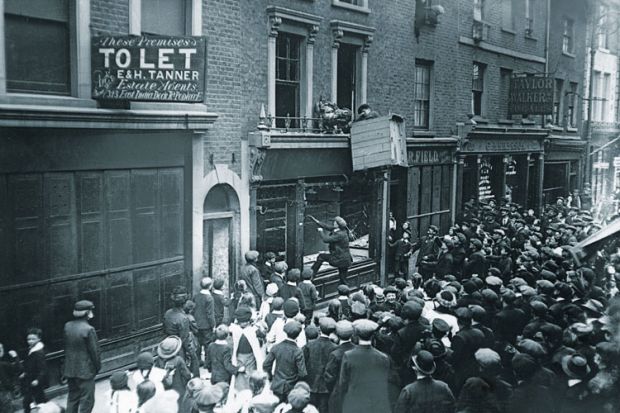

Demonised: as anxiety and fear grew into Germanophobia, German businesses, such as this one in Poplar High Street in London’s East End, were attacked. Some proprietors took steps to disguise their origins

The orientalist and Germanist Carl Hermann Ethé and his terrified wife were left under no illusion as to the possible violent consequences. They hurriedly quit Aberystwyth

Amid the flood of new books, films, television documentaries, musical performances and striking acts of public commemoration, one of the remarkable features of last year’s centenary of the First World War was the amount of attention devoted to life on the “home front”.

Taking impetus from new material discovered by thousands of private individuals and local history groups, often working in tandem with university-based public engagement projects such as the University of Leeds’ “Legacies of War”, each passing day of 2014 seemed to offer new insights into almost every conceivable aspect of the lives of millions of non-combatants in Britain’s towns, cities and rural communities.

Perhaps inevitably, we heard rather less about those local stories that cast Britons in an unfavourable light, particularly when they were about the people in their midst whose German heritage left them facing the harsh and sudden reality of being the “enemy within” in a country that they had long regarded as home.

As attention now turns to the Second World War and the 70th anniversaries of the momentous events of 1945, there is a risk that the fate of the German community in Britain between 1914 and 1918 and its contemporary relevance might be overlooked. One does not need to think much beyond recent events in France, or the growing Islamophobia in many European countries, to imagine the pressures that can build for individuals and families when innocent members of an immigrant community get caught in the crossfire of world events and become the object of suspicion, racist bigotry and hatred.

At the end of 1913, the third largest immigrant community in Britain, including, of course, members of our own Royal Family, was German or Austrian. Numbering more than 50,000, including naturalised British citizens, many were employed in engineering, manufacturing and commerce, while the majority worked in the service industries. Our “German cousins” as they were often known - bakers, butchers, hairdressers, waiters - were a well-assimilated and popular presence on many a high street.

Admiration for German science, art, music, literature and philosophy was, of course, considerable among British intellectuals, and academics from Germany were made welcome in British universities. As the son of an Austrian migrant myself, I have more than just a professional interest in what befell this group of individuals, many of whom had been drawn to this country by British traditions of liberal democracy and the opportunity to play a foundational role in the new redbrick universities established at the turn of the century in the cities of Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds and Liverpool.

Here they worked alongside numerous colleagues who themselves had spent time at elite German institutions, where they had sat at the feet of luminaries such as the chemist Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen, he of the eponymous “burner”. It was arguably also from Germany that the new civic universities imported the notion of the centrality of research together with the dissertation as the quintessential prerequisite for an academic profession. In some senses, the German higher education system provided the blueprint for the expansion of our own, and the range of influence and benefit is often overlooked to this day.

My predecessor at Leeds as holder of the chair in German language and literature was the Göttingen-educated Albert Wilhelm Schüddekopf - its first incumbent. Schüddekopf, who became chair in 1897 and a naturalised Briton in 1912, played a major role in the development of the study of modern languages in this country at university level and, as an assiduous member of the Joint Matriculation Board, in the development of languages curricula in schools. As dean of the Faculty of Arts, he helped to develop Leeds from a science college to a multidisciplinary institution under the visionary leadership of Sir Michael Sadler, Leeds’ vice-chancellor, who looked to models of overseas universities for inspiration and was an avid collector of contemporary German and European art. Immersed in the German tradition of students spending time at several universities, Schüddekopf practically invented the “year abroad”, which remains a central component of languages degrees in the UK to this day. An active researcher, he was also a cultural intermediary, making regular contributions on new writing from England to a German journal. A recent exhibition about the University of Leeds during the war inspired me to learn more about my predecessor’s story, and we would do well to remember it.

With the outbreak of war, the anxieties and fear that had accompanied the growing Anglo-German antagonism of the previous decade – with its “spy fever”, invasion novels and scare stories of the heinous anti-British acts of an alleged German fifth column – quickly transmuted into full-blown Germanophobia. To win over neutral countries, silence dissenting voices, rally the troops and drum up volunteers for Lord Kitchener’s citizen army until conscription was introduced in 1916, the enemy and all those associated with it had to be demonised. Enter the War Propaganda Bureau, ably abetted by big-name writers such as H. G. Wells and Rudyard Kipling (“There are only two divisions in the world today – human beings and Germans”), and nationalist newspapers such as Lord Northcliffe’s Daily Mail, and The Evening News. Most egregious was the rabidly jingoistic mass circulation weekly John Bull, which contrasted quintessentially English qualities of decency, stiff-upper-lip manliness and fair play with the innate savagery of the cowardly, sly and barbaric “Germhuns” and “Austrihuns”.

Anyone living in Britain who was German, of German descent, with connections to Germany and Austria, possessing a remotely German-sounding name or, most bizarrely, with a German breed of pet dog immediately fell under suspicion. New legislation progressively curbed the civil rights of non-naturalised Germans: their clubs and newspapers were shut down, their movements and contacts restricted. They were excluded from social and professional associations, their business assets were sequestered, and large numbers were repatriated or interned in huge camps where they suffered many privations, for example at Knockaloe on the Isle of Man.

Major events in the war played into this discourse, of course, and frequently sparked civic unrest, as valuable work by historians such as Panikos Panayi, professor of European history at De Montfort University, has shown. The wilfully violent German advance through neutral Belgium, for example, brought up to 250,000 refugees to Britain with tales of very real atrocities. Exaggeration and urban myth did the rest. Then a daring early morning bombardment in December 1914 by a German naval battle group left scenes of utter carnage in the genteel Yorkshire seaside resorts of Scarborough and Whitby, and the strategic port of Hartlepool. The assault came as ordinary folk were at breakfast or going about their daily business, and there was profound shock and widespread outrage at this first loss of civilian life on home soil. Zeppelin bombing raids also terrorised urban populations and shook the nation to its core. The illegal treatment of English prisoners of war and the deployment of poison gas by the Germans during the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915 demonstrated beyond doubt Germany’s “cynical and barbarous disregard of the well-known usages of civilized war”, in the words of the commander-in-chief of the British Army.

When, on 7 May 1915, a German submarine torpedoed the passenger liner the Lusitania off the coast of Ireland with the loss of 1,198 lives, it seemed that civilisation as a whole was under threat from a murderous foe that would evidently stop at nothing. In England, vicious large-scale anti-German riots erupted in the Lusitania’s home port of Liverpool and quickly spread, such that troops were required to quell the pogrom atmosphere and restore order. On 15 May, The Manchester Guardian adduced as “evidence of the terror created by the riots” the pathetic queues of desperate Germans voluntarily reporting for internment and grasping at “a chance of reaching safety”. Even naturalised Britons could not feel safe. The very same day, John Bull railed: “You cannot naturalise an unnatural beast – a human abortion – a hellish freak. But you can exterminate it!”

Perhaps the most pernicious manifestation of hostility was the treatment of Germans in public life, as suspicion, xenophobia and resentment frequently morphed into rumour, vicious slander and the wilful destruction of individual livelihoods. As the pioneering work of Christopher T. Husbands, emeritus reader in sociology at the London School of Economics, has shown, many academics became victims of the prevailing anti-German sentiment, with a significant number prevented from returning to their positions or compelled to relinquish them. One such was the internationally renowned orientalist and Germanist Carl Hermann Ethé. A refugee from Prussian authoritarianism, Ethé had served the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth with great distinction for four decades. As papers recently made available online reveal, when he returned home from his annual working holiday on the Rhine in October 1914, his house was besieged by an angry mob of 2,000-3,000 locals whose hostility towards all Germans in their midst had been whipped up by town councillors at a public meeting. On her own at the time in their home, his terrified wife was left under no illusion as to the violent consequences for herself and her husband if they did not leave within 24 hours. The couple hurriedly quit the town that very evening, never to return, leaving behind all their possessions, including the precious books and papers of the college’s one scholar of truly international repute. Other eminent professors, such as Karl Wichmann (Birmingham) and Julius Freund (Sheffield), were removed from office after the coercion of civic authorities. A similar but arguably more tragic case is that of Schüddekopf, who became the victim of a malicious local whispering campaign.

The trouble started in the autumn of 1914. Shortly before hostilities commenced, Schüddekopf’s son, a Leeds-born graduate of the University of Cambridge (where he was a member of the Officer Training Corps), had been invited to apply for a commission as a second lieutenant in the Leeds Rifles. Perturbed by the thought that he might be pitted against his German relations, Schüddekopf senior quietly asked his son’s sympathetic commanding officer to post him anywhere but the Western Front. The officer initially saw nothing untoward in the request. With its combination of Low German and High German double consonants, the name of Schüddekopf is a very unusual one, such that the various Schüddekopfs recorded in databases of German war dead suggest that Schüddekopf senior’s fear was a very real one, not least as many came from his native Göttingen area.

Twisted versions of the story began to circulate, however, and with concerns about the impact on discipline in the officers’ mess, the professor’s integrity and loyalty to the Crown were called into question. When the academic’s wife was overheard in public questioning the veracity of one of the most exaggerated of the Belgian atrocity stories this, too, was held against him. As the general climate of hostility to Germans peaked with the Lusitania riots and as a manifestation of the pressure he was under, Schüddekopf put his name alongside those of four other professorial colleagues who “in view of events” declared in an eye-catching letter to the editor of The Times on 14 May 1915 “unswerving loyalty to the country of our adoption, to which we feel bound not only by gratitude, family ties, and our solemn oath of allegiance, but also by a deep sympathy born of common work and intimate knowledge of the nation’s life and character”. Possibly in a deliberate attempt to publicly discredit him (and thereby the estimated 8,000 naturalised Germans still at liberty), a few weeks later the Unionist MP for York raised the issue of Schüddekopf’s son in the House of Commons and suggested in a parliamentary question to Sir John Simon, the home secretary, that the father and son be interned.

By June 1916, the feeling towards Schüddekopf had been ‘growing stronger for some time past in Leeds and district’ and ‘now reached the point of explosion’

But as arguably the foremost educationalist in the Empire and no stranger to the corridors of power, Sadler was strongly supportive of his beleaguered colleague. With the German “sack” of the medieval library of the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium in August 1914, Sadler went on public record as differentiating between the “downright barbarians, the brood of ruthless war” and “those human Germans, the lovers of learning and science, whom we have respected and shall continue to respect”. He now had the opportunity to be as good as his word and visited Simon to intercede on his colleague’s behalf and to avoid his internment. Schüddekopf, by now suffering from insomnia and nervous exhaustion, received a less severe banning order from the home secretary that restricted his contacts, particularly with any members of the armed forces, and movements under the Defence of the Realm Act. The home secretary explicitly stated that it “implied nothing to his discredit” and compassionately endorsed the suggestion that he withdraw on an extended leave of absence to the spa town of Harrogate, which promised respite and the distractions of a renowned musical scene.

News of the university’s generous decision to honour Schüddekopf three-quarters of his salary brought municipal outrage that the taxpayer should be subsidising an enemy alien. A major stand-off between the university and Leeds City Council rumbled on through the latter half of 1915 until the summer of 1916. A campaign was led by the chairman of the council’s finance committee demanding Schüddekopf’s removal. Regarding himself as his “own Chancellor of the Exchequer”, alderman Charles Wilson had played a central role in raising the “Leeds Pals” regiment with which he maintained a close association. Deploying rumour and innuendo to which Schüddekopf was never given the right of reply, he pushed through a decision to withhold the council’s grant of £5,650 to the university, equivalent to 12 per cent of its total annual income. This was a significantly larger sum than the grant paid by Manchester and Liverpool councils to their universities. Angered by this flagrant attempt to exert pressure by undermining the daily business of the institution, and regarding it as a shameless intervention in the autonomous governance of the university, Sadler, with the full backing of the university, held out for almost a year.

By the middle of June 1916, however, Sadler noted that the feeling towards his colleague had been “growing stronger for some time past in Leeds and district” and “now reached the point of explosion”. The “explosion” probably came two weeks later when news filtered home of the catastrophic death toll at the Somme; among the tens of thousands who died on the first day of the battle on 1 July were 750 of the 900 men of the “Leeds Pals”, leaving barely a home in the city unaffected. The university realised reluctantly that its position on Schüddekopf had become untenable and sought his resignation. Before he could resign, however, the stress of the affair finally took its toll: Schüddekopf died exhausted and broken-hearted after a short illness aged only 54.

In the words of his doctor, the war had killed him “as surely as any bullet has killed the soldiers in the trenches”. The senate of the university passed a resolution expressing its sympathy “deepened by the knowledge of the distress and mental strain which the war had brought on one who had striven for mutual understanding between Germany and Great Britain and whose most cherished hopes were shattered by a catastrophe which, in so far as in him lay, he had endeavoured to avoid”.

By the end of the war, the British German population had more than halved. Those who had remained in the country had been compelled to endure four years of hostility and real hardship, including various forms of persecution. As with the German names of thousands of streets, pubs and public buildings up and down the land, many changed their own to avoid unwanted attention. Even the Royal Family felt obliged to follow suit, with George von Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, also known as King George V, famously becoming the first Windsor in 1917.

The final document in the university’s bulging personnel file on Albert Wilhelm Schüddekopf is a brief letter written by his son in March 1917 giving notice of returning some office keys that he had found in his father’s possessions. In pencil, a third party has noted that the family’s surname had been changed to Shuttleworth.