Where does our world end and the other begin? Britannia Obscura explores an alternative Britain, coursed by canals, imprinted with energy circuits, overflown in airspace. This is meta-geography, seeping outside the Ordnance Survey’s remit, occupying cultural spaces as much as physical ones. In her sublime chapter on caves and caving, for instance, Joanne Parker describes subterranean worlds yet to be discovered, even now, in the 21st century. She relishes the fact that, on our overpopulated archipelago, “it is still just possible to trepidatiously label regions ‘Unknown’. Here be dragons.”

And here be a real Middle Earth explored by Hobbit-like enthusiasts, opening up vast spaces to their first echoes of human voices. Fell Beck’s underground cataract, discovered only in the 19th century, is twice the height of Niagara Falls; a new abyss, Titan, found in 1999, could comfortably house the London Eye. Serpentine passages wind for miles beneath our feet, lakes and rivers never to see the sun, in “a world of green, where the waters are as clear as crystal”.

Meanwhile, up above, are somewhat murkier circuits: the man-made canals that “intravenously” connect derelict nodes of industrial activity. They too seem to elude the modern world, evoking a slower, analogue age. It took 36 hours to travel by canal from Birmingham to London; 137 miles of trudgery for a canalside-trotting horse; 166 locks to pass through. But such a steady pace was invaluable to Josiah Wedgwood, since it delivered his chinaware free of cracks and chips.

Canals were rivals to the roads and railways. Indeed, rail companies would buy up the waterways and cannibalise them; my homeward rail route through Southampton runs directly over a misbegotten canal scheme. Now they have been reclaimed, dug free of mud and weed to become new routes of recreation in a post-industrial world, in the same way that post-Beeching branch lines were reclaimed by walkers and cyclists. “Our rapidly shrinking island seems suddenly to grow again,” says Parker. In the process, we are allowed a new connection with the natural world, a “hidden country…within a kingfisher’s swoop of our office blocks”.

Britannia Obscura especially excels with the prehistoric and the presumptive. Dolmens, menhirs and barrows still invoke mystery, as they did for William Blake, who saw them as agents of “eternal despair”. Parker shows how these sites have shifted in meaning. In the 18th century, the Lincolnshire doctor William Stukeley believed Avebury and Stonehenge to be connected by a snake-like trail, a symbol of immortality on a par with Ancient Egypt. Now some archaeologists see them as little more than sophisticated sundials. Parker wittily describes stone circles as trade fairs for axe-makers, the Olympias of their day.

She enters yet more mystical territory in her chapter on ley lines, “discovered” by businessman Alfred Watkins in the 1920s, when he lined up ancient monuments, medieval churches and geographical features on maps with the aid of glass-headed pins and rulers. Watkins confirmed his conclusions by travelling these “old straight tracks” (echoed in the title of his 1925 book), believing that he had identified ancient routes of passage and trade. In an interwar era of mass trespass on Kinder Scout – and almost as a delayed reaction against 18th-century enclosures – Watkins’ theories gained popularity.

By the 1970s, New Agers were dowsing with bent coathangers in their hands to prove that leys were manifestations of energy circuits embedded in the land. Some suggested that they were the same lines that migratory birds followed (in fact, birds, like whales, do detect electromagnetic paths in the Earth’s surface that aid their ability to travel vast distances). Others believed they led to Atlantis. As a boy, I loved the idea of these invisible evocations of Narnia-like otherness. Even now, standing on Dartmoor’s Brent Tor, a great volcanic plug topped with a stone church, it is easy to look out to the distant horizon and imagine the energy surging beneath one’s feet, sparking and spluttering all the way to the North Sea. Britannia Obscura’s alternative topographies, ancient and modern, speak to our yearning for meaning and pattern. Parker reconnects these fascinating networks and lays them bare – ready for us to impose new mythologies on them in turn.

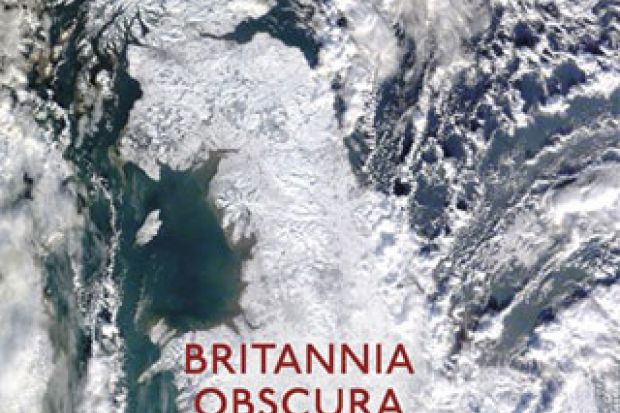

Britannia Obscura: Mapping Hidden Britain

By Joanne Parker

Jonathan Cape, 224pp, £16.99

ISBN 9780224102025

Published November 2014

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login