There is something quite magical about opening one of Gladstone’s own books and seeing the Grand Old Man testily declare in pencil in a margin: ‘If you want apples don’t plant potatoes’

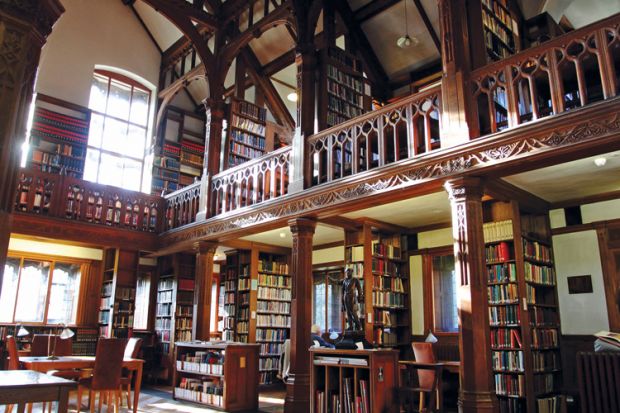

I sit in “Unorthodoxy” and write. Now and then I’ll pull a book off a shelf at random and delight at the neatly pencilled marginalia of another reader from a hundred years ago. For the true bibliophile, books are material objects of desire. Picking up a new book, or a very old one, and anticipating its content with a caress of its boards or an inhalation of its redolent scent, is the intellectual foreplay that precedes the consummation of the act of reading. My favourite desk at Gladstone’s Library in Hawarden, North Wales, is surrounded on three sides by books whose shelves are labelled “Unorthodoxy”, but readers and writers in other sections might rub shoulders with, for example, “Celibacy”.

When I first stayed overnight at this unique residential prime ministerial library, more than a decade ago, it was an austere space with shared bathrooms, a capricious heating system and lumpy mattresses that I imagined were stuffed with the discarded horsehair shirts of earlier residents. Now, though, it’s an institution that has fully embraced the needs of discriminating 21st-century travellers. The residential wing is more boutique hotel than hermit’s cell. Its rooms are warm and comfortable, with chichi Welsh slate en suites and a sleek John Lewis aesthetic, complete with a retro Roberts DAB radio in each room.

When I stay here, which I do whenever I’m working on a major piece of writing, I leave the reading rooms when they close at 10pm, and I’m intellectually exhausted and physically stiff from a 12-hour writing stint. I go up the main staircase to my room and bed, tweaking the nose of the bronze bust of Gladstone on the landing and whispering “Goodnight, and thank you” as I pass.

Because the library is residential, with meals cooked and rooms cleaned, putting the auto reply on my email leaves me free to read and write. Being surrounded by the quarter of a million volumes it now owns feels simultaneously inspiring (“All these books! I, too, can write!”) and overwhelming (“All these books! Does the world need mine?”). Gladstone’s Library is a convivial, supportive space, but if some unsuspecting unfortunate should be working at My Desk, I will petulantly choose another one and watch and wait, until the reprobate vacates Mine. I rarely move as fast as I do then; like a Brit on a package holiday putting her towel on her favourite poolside sunbed before dawn, I pounce, indecorously hurling down notebooks, pens, laptop and books as placeholders.

The irony’s far from lost on me that I am a woman who writes on feminism in a setting created for me by William Ewart Gladstone, who, in 1892, wrote to the MP Samuel Smith to reiterate his opposition to female suffrage. “I recognize the subtle and profound character of the differences between [the two sexes],” he said, “and I must again, and again, and again, deliberate before aiding in the issue of what seems an invitation by public authority to the one to renounce as far as possible its own office, in order to assume that of the other.” Yet my bedtime thanks to the Grand Old Man are genuine, and sparked by his extraordinary vision. Gladstone was prime minister no fewer than four times, but he still carved out the space and time to build up a personal library of 32,000 books, of which he read a staggering 22,000. (I blame John Logie Baird, Netflix and HBO, in pretty equal measure, for my own paltry tally that probably lies somewhere shy of 2,000.)

In the late 1880s, Gladstone erected two temporary corrugated iron buildings (the “Tin Tabernacle”, later known as St Deiniol’s Library) on the site where the library now stands, complete with study rooms, to house his books and to make them available to members of the public. He was in his eighties, but still took up his wheelbarrow and personally moved some of his extensive collection the quarter of a mile from his home, Hawarden Castle. As his daughter Mary Drew recalled, he was “often pondering how to bring together readers who had no books and books who [sic] had no readers”.

When Gladstone died in 1898, his bequest to his library was a massive £40,000 – equivalent to about £3.5 million today.

The problem so many of us face, of how best to keep and display our beloved books (for Anthony Powell was right – they do absolutely “furnish a room”), greatly exercised Gladstone in the years before his death.

In 1890, he published an essay, “On Books and the Housing of Them”. “Books are the voices of the dead,” he declared. “They are a main instrument of communion with the vast human procession of the other world. They are the allies of the thought of man…In a room well filled with them, no one has felt or can feel solitary.”

“What man who really loves his books delegates to any other human being, as long as there is breath in his body, the office of inducting them into their homes?” he wrote. The permanent library structure, and the one today’s visitors see, opened in 1902; the first residential reader stayed in 1906.

Gladstone was an altruistic bibliophile, and remains the only British prime minister to have bequeathed a library to the people. There is, of course, since Franklin Roosevelt, a long tradition of US presidential libraries, although George W. Bush will hardly be remembered as a great reader and thinker in the Gladstonian vein. Closer to home, a memorial library for Margaret Thatcher has long been mooted. She was about as enthusiastic a reader as Bush, and the attitude to public libraries of some of her Conservative successors would have made Gladstone shudder. In February 1891, he opened the St Martin-in-the-Fields Public Library (off Trafalgar Square), saying that: “On every ground I feel that in taking part in inaugurating and in commending to public notice and public interest this library, every one present is discharging a valuable and important public duty.”

It’s a sentiment that clearly resonates for the warden of Gladstone’s Library, Peter Francis. In his 18 years, he has steered the library’s remarkable evolution from tired, regimented book repository with accommodation to the vibrant place it is now. That the Eames-meets-William Morris design scheme works so well is due in no small part to the vision of Francis and his team. His firm belief that “Gladstone’s books were there to be read and to form the basis of a working library, not to be shut away” has paid off – there really is something quite magical about opening one of Gladstone’s own books and seeing the Grand Old Man testily declare in pencil in a margin: “If you want apples don’t plant potatoes.”

Francis is characteristically good-natured about the prospect of a Thatcher library (“Good luck to them – if you wanted to make money, a library’s not necessarily the way you’d choose to do it”) and is clear that he wants to maintain the founder’s vision. But if the three main areas of Gladstone’s own books – theology, literary culture, and history and politics – are still reflected in the acquisitions policy, the incredibly successful writers in residence scheme and the annual “Gladfest” and “Hearth” literature festivals represent major new departures. There are also plans, as Francis puts it, to “revivify the political” in the not too distant future, by offering residential schemes for political writers, in addition to those for novelists and poets.

For those of us exhausted by our quotidian responsibilities and who are used to having to fit in our thinking and writing around other academic duties, sometimes with detriment to both health and family life, Gladstone’s Library offers the milieu to carve out a meaningful period for reading, writing, thinking or – heaven forfend – simply unwinding. It’s an exceptional institution where seriousness and laughter, and camaraderie and solitude, have a vital place, embracing the modern world while continuing to rejoice in the unsurpassed wonders – both physical and metaphysical – of books.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login