Never before has the idea of the university been so feverishly debated in England, and for good reason. The restructuring of the country's higher education sector around a student-debt-financed, fee-driven model is a fundamental recasting of the university's place and purpose in society. But this process did not begin with the government's higher education White Paper or even with the Browne Report that laid the ground for it. And neither is it confined to the UK.

The neoliberal transformation of higher education is a global phenomenon. In the Americas, Europe, Russia and its former colonies, the Middle East, Africa, South Asia and Australasia, higher education is being rebranded as a private investment and the university repurposed to generate profit and economic growth. As a consequence, academics and students are confronting very similar conditions across the world: the escalation of fees and student debt, the expansion of management and administrative systems for measuring the efficiency of services, the quest for a plethora of new types of fee-paying consumers, and the casualisation of academic labour.

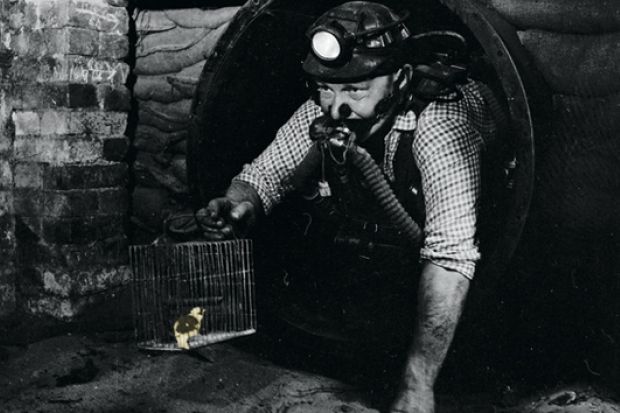

Nonetheless, England's university system - which Howard Hotson has shown to be the best publicly funded system in the world - has been privatised further and faster than anywhere else. Despite the many exposés of the flawed rationales, contradictory mechanisms and indecent haste of this process, no one has yet asked why it has happened in England. Remarkably, the story of how English universities became the canaries in the coal mine has gone largely untold.

That story begins with the Robbins Report of 1963, which is often assumed to have ushered in the golden age of the publicly funded university. The year after the Conservative government convened the Robbins commission in 1961, there were just 118,000 undergraduates (4 per cent of their age cohort) attending 31 universities. This was a considerable advance on the mere 50,000 students (1.7 per cent of their age group) who went to university in 1938, and it was made possible by the scholarships provided through the Education Act of 1944 as well as a trickle of new campuses at Nottingham, Southampton, Hull, Exeter, Leicester and Keele. Nonetheless, by 1963, fewer than one in 100 working-class children made it to university. The 8 per cent of young people who were privately educated accounted for just under 40 per cent of university places.

The Robbins Report concluded that universities should become more socially democratic places and that they should double their student numbers in 20 years. It was a commitment welcomed by the new Labour government of Harold Wilson in 1964, which immediately introduced a system of universal grants. With Tony Crosland as minister of education and science, the universities were to be engines of social mobility and equality of opportunity. By 1970, the higher education sector had already reached Robbins' target, with 219,000 undergraduates (9 per cent of the age cohort). The size of the direct grant that went to universities, through the entirely autonomous University Grants Committee, was proportional to the numbers of students they admitted.

But despite Crosland's commitment to equality of opportunity through education, infamously articulated in his pledge to destroy "every fucking grammar school", he left private schools untouched and created a new binary system of higher education. The new polytechnics, with their primary focus on teaching the "practical" and not the "liberal" arts, were designed to have less prestige than universities. In 1970, they boasted a student population that nearly matched those of the universities.

With this new Keynesian model of higher education, the promise of social mobility lay dormant. Between 1971 and 1987, the percentage of young people in higher education remained essentially flat, at around 14 per cent, with the numbers evenly divided between universities and polytechnics, and higher education as a whole remained the domain of the privileged.

In the post-Robbins era, higher education became vulnerable to the assaults of Thatcherism on two fronts. First, the failure to make higher education more socially democratic was used by Margaret Thatcher and her two reforming ministers for education, Keith Joseph and Kenneth Baker, as the basis of a populist critique that public funds were being used disproportionately to support middle-class students and their equally privileged teachers. The nebulous rhetoric of "fairness" and "access" used to justify the current restructuring of higher education is rooted in this critique. Second, the highly centralised nature of the funding system made the sector susceptible to state-driven reforms designed to make universities more productive and less privileged places. This led to the creation of a "market" - a series of simulated competitive environments for the distribution of research funds, postgraduate students and undergraduates - engineered by the state.

The attack on universities as the bastions of privilege began to bite with the budget cuts introduced by Geoffrey Howe in 1981. From the vantage point of last year's Comprehensive Spending Review, the Howe cuts seem decidedly undraconian: higher education took a general 11 per cent hit. However, the cuts were distributed unevenly by the University Grants Committee, so many campuses experienced the rounds of department closures, early retirements and freezes on appointments that were then exceptional but are now routine.

Worse still, Howe's budget broke the post-Robbins compact that funding would rise or fall in relation to the size of the undergraduate population. Thereafter the pattern was to squeeze more out of universities for less. As funding fell and the number of university teachers remained static, student numbers rose during the late 1980s and the unit cost of undergraduate education was dramatically reduced. In 1980, for every university teacher there were nine students. By 1990, that had risen to 13 and by 2000 to 17.

Meanwhile, academic salaries remained essentially stagnant in real terms between 1981 and 2000. The new post-1981 funding regime was designed to end the privileged conditions of university teachers and students alike. Joseph abolished the universal minimum grant in 1985 and three years later it came as no surprise that the abolition of tenure was added, almost as a footnote, to the Education Reform Act of 1988. That same act ended the fabled autonomy of higher education as the University Grants Committee was replaced by the ministerially appointed Universities Funding Council (the predecessor to the Higher Education Funding Council for England) which included "experts" from outside the sector chiefly from the world of business. The writing was on the wall.

Just as the Education Act of 1988 inaugurated a far larger role for the state in primary and secondary education, so it manufactured new markets for the distribution of resources for which universities would have to compete. While the research assessment exercise (1986) and the newly created research councils (1992) compelled universities and their staff to compete for research income and rankings, the teaching quality assessment (1993) measured and ranked the quality of teaching so that students could make more informed choices as consumers of these services. These state-sponsored forms of competition and auditing created a binary market in higher education: one for institutions competing for research income, the other for students as consumers.

Whether competition for resources or for higher rankings has improved the quality of research or teaching at UK universities is debatable. It has, however, created a new academic culture in which those who worked and studied at universities have largely internalised the new market rationalities. Over the past generation, a new breed of entrepreneurial academics has emerged whose career advancement and understanding of their job is structured around state-imposed metrics of value, recognition and reward.

I was one of them. I began my doctoral work in 1987 and got my first job in 1991 as this new culture was being embedded. Impatient with my older colleagues' nostalgia for a pre-Thatcher golden age of the university (which was always white and male), I welcomed the new flexibility in the job market, the opportunity to rethink what and how we taught, as well as the apparent transparency of the competition for research funds and postgraduates that did not appear loaded in favour of the "golden triangle" of the universities of London, Oxford and Cambridge. I talked the talk and was rapidly promoted.

We all know the type - the young, smartly dressed professors who publish more than they should and measure the importance of their work by citation indexes and media invitations. This new breed collects postgraduates with little regard for their dismal futures within the academy and has an uncanny knack of winning research grants that rely upon an army of casualised research assistants and replacement lecturers on short-term contracts.

This is a caricature to be sure, but it is one that speaks to a culture of advancement that is now so naturalised that the term "entrepreneurial" has actually become a term of academic praise. In this sense, few of us are not complicit in the system that has allowed A.C. Grayling and his fellow mercenaries to trade their reputations for cash through an exclusive, private college.

Is it any wonder then that, despite the continuing protests, the majority of students and their teachers are resigned to the privatisation of higher education in England? Many, it seems, have accepted the logic that the public funding for higher education was only possible when the system educated only a privileged elite. It is as if the public value of higher education somehow mysteriously evaporates when it is more democratically available. Instead of making funding for a socially democratic university an issue of social justice and civil rights, most university administrators and teachers - beguiled by the promise to restore funding and salary levels despite dwindling levels of public investment - did not protest against the introduction of fees in 1997 or their extension in 2004. Academic salaries did indeed rise after 2000 but, by 2009, funding per student had recovered only to its 1992 level. From here, it was but a small step to the Browne Report's recommendation that student fees and loans should not just supplement public funds but, in some subjects, entirely replace them.

Absurdly, we are now expected to believe that if universities are to finally achieve Crosland's promise of providing equality of educational opportunity and social mobility, it must come at the personal expense of the students who benefit. This view of education as a personal investment, a hedge on future status and income, is only new in relation to universities. The private model of education has a long history in the primary and secondary sectors. During the 1950s and 1960s, many in the Labour Party argued that achieving equality of educational opportunity required not just ending the 11-plus and selective grammar schools but abolishing private schools as well. The privately educated Crosland oversaw the creation of the Public Schools Commission in 1965 to honour the Labour Party's 1964 manifesto commitment to figure out "the best way of integrating the public schools into the state system of education".

Happily for Wilson's government, which was ambivalent on the issue, the Commission's report in 1968 was a muddle. Although calls for abolition continued at Labour Party conferences throughout the 1970s, the last manifesto commitment came in 1983.

In contrast, private schools, rebranded as the "independent sector", found strong advocates in Thatcher and Joseph. As shadow education secretary from 1969, as well as minister for education between 1970 and 1974, Thatcher wanted to expand access to private schools, a policy her government pursued. While the relative size of the independent sector had been in decline since 1964, it began to rise again steadily from a nadir in 1979 when it represented less than 6 per cent of school children and 8 per cent of schools. By 2006, those figures had climbed to 7.5 per cent and more than 9 per cent - and this was despite average fees escalating in real terms from just below £8,000 to £20,000 between 1981 and 2006. Clearly, a growing number of parents were not only able to pay for their child's education but believed that doing so represented an investment in their future income and status. The view of education as a private investment, as insurance for a brighter and better future, began with independent schools.

Preventing the headlong rush to a new idea of the consumer-orientated and profit-centred university requires more than outrage, protest or even the publication of alternative White Papers, necessary as all of them are. We must first try to understand how we arrived at the point where a redirection of public funds to support sub-prime loans for student-debt-financing of higher education seemed natural and inevitable. It is no longer sufficient to nostalgically invoke a better idea of the university, of a golden age of public funding, without understanding how it became so vulnerable to a critique that has eventually eviscerated it.

While the words "access" and "fairness" are abused by ministers, these terms speak to a continuing belief among the electorate that universities are powerful engines of social mobility. It is this idea we must appeal to if publicly funded university education, which enriches not only the lives of individuals but our collective life as a society, is to be a civil right for all.

Higher education participation rates over time

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login