A senior research fellow at the State Archive of the Russian Federation and a widely published expert on the Soviet Union, Oleg Khlevniuk rightly claims that it is now feasible “to write a genuinely new biography” of Joseph Stalin, “insofar as newly accessible archival material has forced changes in our understanding of both the man and his era”.

We learn that Stalin became a workaholic, a hands-on leader who even on vacation would receive 50 letters and reports each day, many requiring written responses. In Moscow or at his dacha, he routinely held meetings long into the night; in fact, over a 30-year period, some 3,000 people visited his Kremlin office. But what deep passions drove this enigmatic character, devoid as he was of a loving companion in the last 20 years of his life, and what really made him tick?

Although Khlevniuk’s answer to that question, and the theme of his book, is that Stalin relentlessly strove for power, surely we need to go further if we want to understand his behaviour. It was not simply a matter of power for its own sake, for we can interpret the sources to show that Marxism-Leninism provided the red line that ran through the man’s entire adult life. That ideology provided the key to his understanding of the world, although it also led him to make atrocious errors. Perhaps the most tragic of these was his conviction that faithful economic appeasement of Hitler in 1939-41 had made a Nazi invasion needless, and thus unthinkable, even as his best spies relentlessly reported otherwise. At the same time, Stalin was almost alone in recognising the social and political ramifications of the Second World War, and in deducing that Hitler, without knowing it, was playing a revolutionary role in annihilating Europe’s ruling elite, thereby preparing the ground for Soviet-style socialism. Along with a keen sense of what was possible in global politics, Stalin’s mission was to make communism work in the USSR, regardless of the costs, and then to spread its liberating gospel to Europe and beyond.

The author organises the book with a prologue to each chapter that singles out an episode in Stalin’s last days in March 1953, along with reflections on various matters in his life, after which we get a political narrative of the major periods in the dictatorship. There is little social history, surprisingly few details about the dictator’s intimate life, and it is curious that we meet his immediate family, and briefly, only in the prologue to the final chapter.

The two-track storyline occasionally sends mixed messages, such as on Stalin’s role in the horrendous famine of 1932-33. In one prologue early in the book, we read that the government used starvation as a means of “punishing” the countryside, and that Moscow rejected “all opportunities to relieve the situation”. Here, Stalin’s decisions sound unequivocal and indicate that he intended mass murder, whereas much later in another chapter we learn that the dictator agreed, albeit too late, to a reduction in grain quotas in 1933. Even then, he blamed the enforcers and administrators for being weak-willed, because he would never admit that there were flaws in his big plans.

Khlevniuk elides a number of issues, such as Lenin’s decision to abolish freedom of the press within days of taking power, and also to establish the secret police before the end of 1917, and then to shut down the constituent assembly in January 1918. The Soviet dictatorship is here presented as if it were Stalin’s invention, when in fact the Bolsheviks established the system and got it running before he became the unchallengeable boss.

Elsewhere, Khlevniuk passes over problems that have plagued historians for decades. To mention one example among many, the text leaves us wondering why the Soviet boss apparently became anti-Semitic during the Second World War. Although the Red Army liberated the death camps, on Stalin’s orders the regime posthumously converted the murdered Jews into “ordinary Soviet citizens”. So in the decades that followed there would be no place for the Holocaust in the history of the Great Patriotic War anywhere in Eastern Europe, but why not?

Questions inevitably linger about a figure as complicated as Stalin, and historians will welcome this remarkably informative book, just as all readers must applaud the author’s courageous and conscientious efforts to uphold the highest standards of historical scholarship.

Robert Gellately is professor of history, Florida State University, and author, most recently, of Stalin’s Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War (2013).

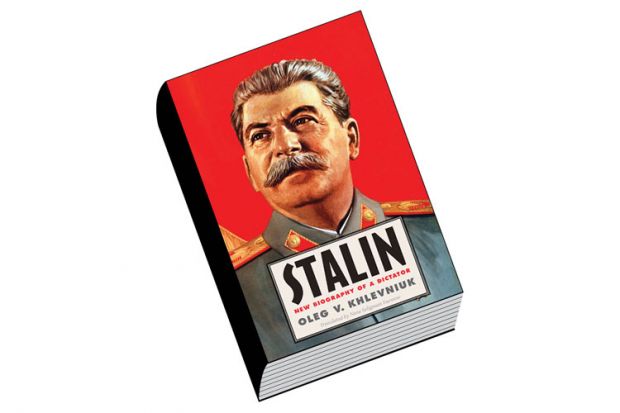

Stalin: New Biography of a Dictator

By Oleg V. Khlevniuk

Yale University Press, 408pp, £25.00

ISBN 9780300163889

Published 19 May 2015

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login