Would you kill the fat man? David Edmonds says he would. For all their moralising, or perhaps because of it, philosophers are a politically incorrect bunch.

Here and there are flashes of the insight that made Edmonds’ Wittgenstein’s Poker (co-authored with John Eidinow) briefly light up the philosophical firmament – to the extent to which (to my irritation) I was obliged to have a book retitled to include the Austrian philosopher’s name.

Wittgenstein makes only a guest appearance here, prefaced by the over-enthusiastic assessment that his genius, beguiling prose and mesmerising charisma “combined to make him the most influential philosopher in the Anglo-American world”. (With such status, one wonders why he ever felt the necessity to resort to waving pokers to make his points.)

This time, though, the idea is that people can be taught about ethics without them realising it. Hence, the book is presented as a whole series of (at first) exciting and intriguing trolley scenarios, bracketed by colourful but essentially irrelevant biographical details of various academics. Alas, by the final chapters, the novelty has faded and the device becomes rather fatiguing.

Edmonds does a fair job of introducing the central planks of philosophical ethics: the false promise of Kant’s imperatives; the inescapable gravitational pull of utilitarianism; the recent resurrection of Aristotle’s zombie theory of virtue ethics. Not that he puts it quite like that – indeed, virtue ethics is offered as a brilliant rediscovery of an idea that had been otherwise almost entirely abandoned, “at least in Oxford”.

In fact, this book is built on a particular conceit, which is that Oxbridge philosophers invented most of the ethical debate. Trolley dilemmas, after all, were conjured unexpectedly into being by Philippa Foot, with the help of Wittgenstein’s then acolyte and later biographer, Elizabeth Anscombe (arguing with whom was like “having your skin ripped off”, says Edmonds). Iris Murdoch was present, too – “the gifted have a tendency to cluster”, says Edmonds – and “when a young Tony Kenny arrived in town”, the scene was set for, well, a trolley accident. Yet the core idea of weighing up imaginary outcomes to test our ethical intuitions is as old as anything in philosophy.

That’s why, when Foot introduced the first trolley dilemma, in a short article in the Oxford Review in 1967, as part of an ongoing debate about abortion rights, it was soberly headed “The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect”.

The doctrine of double effect is the “big idea” in this book, and supposedly explains at least some of the contradictions that can be seen in our responses to ethical dilemmas. In a nutshell, it is the notion that you can split the consequences of your actions into two kinds – those you necessarily intend, and those that just happen anyway. As many an internet wag has put it, the doctrine looks rather like an excuse to do anything you like: the “doctrine of everyday life”. Nonetheless, Edmonds’ argument is that in the trolley dilemma, the saving takes place first, and the dire consequences may or may not follow, whereas say, with transplants, the method requires the unpleasant first, and the good things follow after – “we do not intend to kill the single man…but we do intend to kill the single patient whose organs will save five lives”.

But there’s more than this hanging on the resolution of the dilemma. “The trolley problems may indicate that human morality is innate – and that, for example, the doctrine of double effect, first expounded nearly a millennium ago by Saint Thomas Aquinas, is hardwired into us,” argues Edmonds. In this vein, excursions into Chomskyan grammars and neuroscience follow.

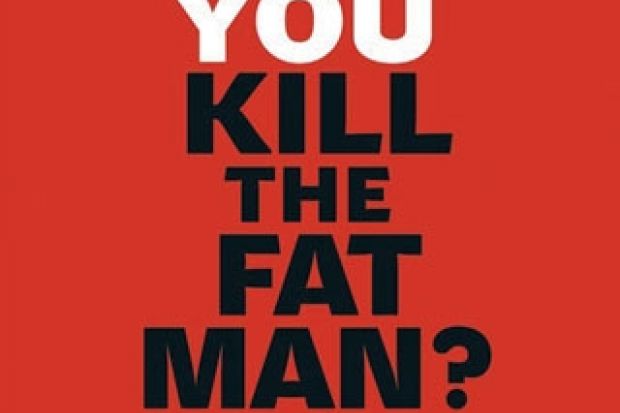

Would You Kill the Fat Man? The Trolley Problem and What Your Answer Tells Us about Right and Wrong

By David Edmonds

Princeton University Press, 240pp, £13.95

ISBN 9780691154022 and 9781400848386 (e-book)

Published 23 October 2013

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login