Only a few years ago, a high-flying female diplomat (later to be the UK’s ambassador to the Vatican), during an early secondment to the home Civil Service, was automatically assumed by a roomful of male officials to be a mere secretary, clearly present at the meeting only to hand out their documentation.

Such experiences have been all too common as women have slowly fought their way up the ranks. In the home Civil Service, women have been eligible to apply for the senior grades since the 1920s, although only a few have reached (nearly) the very top. In the more complex world of diplomacy, for the reasons analysed in this illuminating book, the obstacles have been more serious: until 1946 women were excluded from diplomatic appointments altogether, until 1973 they had to resign if they married, and even the increase in recruitment and promotion since the 1990s has produced practically no female appointees either to major ambassadorships or to the top management of “the Office” itself.

Helen McCarthy, an authority on the social context of UK foreign policy, focuses here on the very heart of the diplomatic machinery, the top echelons of the Foreign Office (from 1968, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office), and the laborious overcoming of their resistance to reform.

The debate became active after the First World War, which had seen the increased employment of women in clerical and other subordinate jobs. As to their suitability for diplomatic appointments, the basic arguments on both sides remained constant for two decades. The Foreign Office’s traditionalists argued that female ambassadors would be ineffective or even unacceptable in many societies; that women would be unable to withstand the rigours of some foreign climates or to manage consular tasks such as controlling drunken sailors; and even, as the respected guru Harold Nicolson put it, that women’s characteristic qualities of intuition and sympathy for others could become positive liabilities in the tough world of diplomacy. In response, as time went by, the increasingly weighty pro-reform lobby was able to argue that certain distinguished women (such as Gertrude Bell and Freya Stark) had shown their diplomatic mettle in two world wars, or in senior positions with the League of Nations or the International Labour Organisation; that some countries, including the Soviet Union and the US, sent female diplomats abroad as early as the 1920s; and that society’s attitude to women (especially to the growing numbers of highly trained ones) had changed fairly radically since 1914.

This was the background to the Foreign Office’s change of view after 1945, and to the ensuing trickle of female appointees, some of whose experiences McCarthy engagingly and illuminatingly recounts. She describes the well-known case of the experienced and outstandingly talented Pauline Neville-Jones, who was told towards the end of a brilliant career that she could not be ambassador to France as she wished, but “only” to Germany (at which she resigned, becoming a banker and then a life peer and government minister). As McCarthy emphasises, Neville-Jones’ supporters denounced the FCO’s decision as gender-based discrimination, but other factors must be considered. Ambassadorial appointees very often have already served in a junior capacity in the post in question, acquiring a stock of local knowledge and a potentially precious network. When McCarthy says that Neville-Jones had served in Bonn, she makes this sound like a reason why the ambassadorship, from this diplomat’s point of view, “had to be Paris” – though Neville-Jones had never served there, whereas her rival Michael Jay (like most British ambassadors to France) had.

Shortage of space prevents McCarthy from going into full detail on many aspects of her wide-ranging subject. Readers interested in tracing individual careers will sometimes be confused by the discriminatory convention that women, unlike men, are expected to change their surnames on marriage, and the fact that McCarthy, tending to give only the married names, obscures, for instance, that “Juliet Campbell” or “Catherine Hughes” spent most or even (for the latter) all of their diplomatic careers as “Collings” and “Pestell” respectively. Overall, this pioneering study gives a penetrating, readable and most welcome introduction to a neglected set of issues, and will be gratefully received by a wide readership, including future researchers to explore these important issues further.

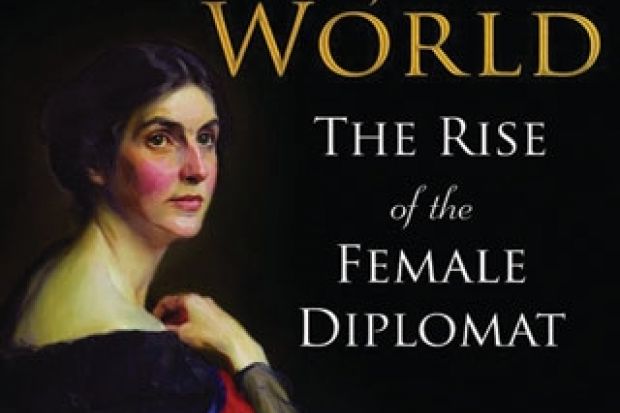

Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat

By Helen McCarthy

Bloomsbury, 416pp, £25.00 and £21.99

ISBN 9781408840054 and 0047 (e-book)

Published 22 May 2014

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login