Marina Warner's compelling new study of fairy tales, From the Beast to the Blonde, is a major retelling of the myths and theories of folklore scholarship, women's studies, and popular culture. Her thesis is that a narrator of fairy tales such as Mother Goose is not simply a convention of oral transmission but a figure that encodes important social truths about storytellers, particularly female storytellers, and their concerns. Warner is not content, however, just to blur the line between texts and contexts: she gives such a dazzlingly erudite reading of the figure of the tale-teller that Mother Goose may never be the same again: her goose is thoroughly cooked.

In the first half of the book, Warner examines the status of fairy tale and its tellers; in the second half she considers a handful of specific tales, Cinderella, The Sleeping Beauty, Bluebeard, Beauty and the Beast, Donkeyskin, The Little Mermaid, which are all concerned with women's roles and rivalries.

Warner is not merely a feminist critic of fairy tale. She does not simply expose fairy tales as myths of patriarchal oppression or phallic Freudian sexuality, and moreover she rejects the definitions of folklore as either an archetypal language or a diffuse process of transmogrification. She proposes a rather different form of fairy-tale analysis: a genealogy of the fairy tale. Warner argues that fairy tales are secret histories: they are records of female utterance and texts of matrilineal storytelling, they disclose a "doubled aspect of femaleness" -- which is "the record of female experience in certain tales, and . . . the ascription of a female point of view, through the protagonist or the narrating voice". The often grotesque figure of the storyteller is also part of this tradition, but in a different way: it is a demonisation of the monstrous power of the female imagination. Fairy tales and their tellers therefore describe gender relations, and in the ritual of transmission they constitute those relations within a domestic sphere. In doing so, they promote a sense of social identity. Yet fairy tales are highly ambivalent social documents; like old wives' tales they mix proverbial wisdom and dangerous folly.

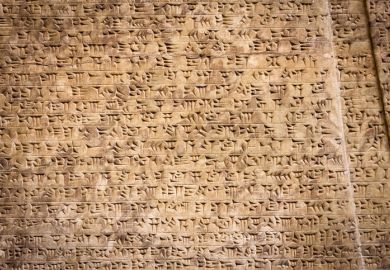

Warner focuses on the moment when male writers disseminate women's stories, and she describes the process by which the female teller is written into the tale, stressing the importance of female sources for male collectors such as the Brothers Grimm and Elias Lonnrot (compiler of the Kalevala). Oral storytelling relies on the management of social space, and especially on the delineation of female space in places of restriction and boredom: places of repetitive domestic work and limited pedagogic opportunity. Of course these spaces are also secret channels for the transmission of tales and are chthonic sites of domestic power, folkloric wisdom, and oracular soothsaying as well. As Warner puts it: "Women's power in fairy tale is very marked, for good and evil, and much of it is verbal: riddling, casting spells, conjuring, hearing animals' speech and talking back to them, turning words into deeds according to the elementary laws of magic, sometimes to comic effect. Women in fairy tale align themselves with the Odyssean party of wily speechmakers, with the Orphic mode of entrancement, with the Aesopian slave tradition of fabulism."

This is most spectacularly demonstrated by Warner's treatment of Mother Goose: an old goose, very hard to pluck, but marvelously formed beneath her feathers -- and very tasty to boot. Warner serves up Mother Goose as an historical dish flavoured with the sybil, Saint Anne (mother of Mary), the Queen of Sheba, and the proverbial old crone. The mixing of classical, biblical, mystical, and domestic ingredients in her readings produces an intriguing and engaging new Mother Goose.

Saint Anne takes on a symbolic sybilline role as the prototypical "Nanny" and walks upon Sheba's crooked foot, which is variously considered as a hairy leg, a monstrous and webbed (goose) foot, and a storyteller's splayed foot deformed at the spinning wheel. Warner reads these episodes very subtly; she resists the temptation to see an archetypal significance in the repetition of elements but proposes that they are drastically reworked and retold tales that continually construct a new set of tale-teller identities.

Warner typically offers a rapid survey of different versions of a tale, before settling us down to an account of its historical development and finishing up with a reading of a particularly rich version. Along the way she offers remarkable little disquisitions on such subjects as hair and beards and their associations of barbarism, exoticism, and sexual appetite; on the implications in Cinderella of the death of a parent and the ensuing attempts by the family's womenfolk to exercise their influence through the medium of tale-telling; and on the etymology of the "gossip", who began life as a friend invited to the christening of a child and developed on the one hand into a god-parent and on the other into an idle chatterer. It is a narrative which unravels narratives, in effect post-modern antiquarianism. "Pretences, ruses, riddles are the stuff of fiction, and in fairy tales they often become pivotal in the plot" -- they are indeed pivotal in Warner's own account. What is sauce for thegoose is sauce for the gander. The emphasis on tale-tellers calls into question Warner's own status as teller of fairy tales (albeit in an academic context), and her own employment of fairy-tale motifs such as riddles, strange lore, secret histories, and arcane insights suggests that the zest and ingenuity of her interpretation is a prime example of the traditional female wit of a fairy-tale heroine. Not only does Warner display a barely suppressed pleasure in joining the tradition of telling tales -- her account is highly absorbing, extremely energetic, and very entertaining -- but her erudition and wit brings to the book "a slightly sinister atmosphere, the authentic recipe of frivolity, dreaminess, blitheness and sadism that we now recognise as the essential tone of fairy tale".

These might be the aesthetics of a new antiquarianism; Marina Warner is reinventing the fairytale for a post-modern academy.

Nick Groom is a lecturer in English literature, University of Exeter.

From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers

Author - Marina Warner

ISBN - 0 7011 3530 1

Publisher - Chatto and Windus

Price - £20.00

Pages - 458pp

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login