Someone at Penguin has developed a clever series of small books offering lively accounts of Britain’s rulers since Athelstan. They are neat little hardbacks, one monarch per volume, nicely bound in uniform white, with widely spaced type, well illustrated with colour plates and furnished with references, further reading and an index. Half-sized dust jackets carry the colour and variety to the bookshelf.

Unless the idea for the entire series was Jane Ridley’s, I presume that she wrote this one on Queen Victoria to commission. She has made a good fist of it: her book is a rattling good read. If the other volumes are as well done as hers, the entire series from Wessex to Windsor will be a winner.

Victoria had a very long reign (1837-1901). She left behind a surfeit of data, including volumes of her own (edited) letters, houses, monuments, costumes, jewellery and objects, and a colossal cultural legacy. The intervening century (and a bit) since her death has allowed both the landmarks to become more visible and the writing of a number of biographies. Ridley has mined them all and acknowledges her debts at the outset. She pays especial tribute to the perspicacity of Lytton Strachey, whose 1921 book, Queen Victoria, she describes as a masterpiece.

Strachey is a hard act to follow, but Ridley manages it with a brisk kind of modesty, charting the major episodes of Victoria’s life from circumscribed childhood to long widowhood without flagging, allowing each its proper space. It is a personal history of growth and change, given often in Victoria’s own words, interwoven with the politics of the day. So while Victoria is the focus, the changing context of her era is there, too. The only disappointment is the book’s abrupt ending: Victoria dies and that’s that. There is no summing up.

Victoria’s dynastic inheritance from her disreputable old uncles had already been moderated by Queen Adelaide. But Victoria’s court represented a significant change, especially after her marriage to Albert and the arrival of their many children. Ridley deals well with Victoria’s struggle to reconcile queenhood with wifeliness while Albert lived. Even in the depths of her 40-year grief after his unexpected death in 1861, and despite close liaisons with a succession of male commoners – politicians and servants – Victoria kept her grip on power.

Perhaps the most telling moment is Victoria’s behaviour at her accession. On 24 May 1837 she turned 18, depriving her widowed mother the Duchess of Kent and her henchman Sir John Conroy of the regency they had hoped for. She had been cosseted and watched all her childhood, dominated, manipulated and coerced by her mother and Conroy, never for a moment left alone.

William IV died during the night of 20 June; early that morning, the teenaged Victoria chose to meet the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chamberlain on her own. When Lord Melbourne, the prime minister, arrived at Kensington Palace she met him alone, and she held her first Privy Council alone, too. As soon as Victoria had the power to do so, Conroy was banished and her mother was expelled from her presence. The word used to describe Victoria by a contemporary diarist was “resolute”. She remained so for the rest of her life.

Ruth Richardson is visiting research fellow, Centre for Life-Writing Research, King’s College London.

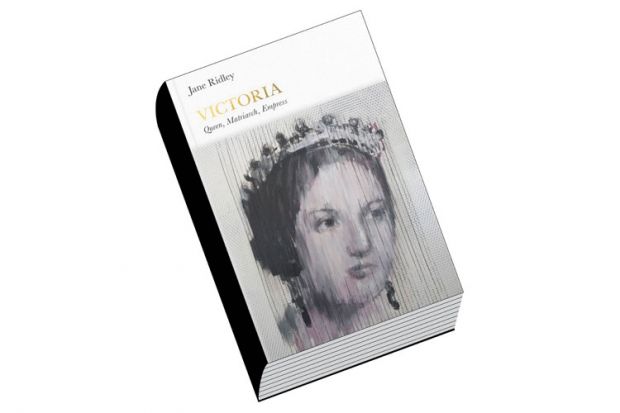

Victoria: Queen, Matriarch, Empress

By Jane Ridley

Penguin, 160pp, £10.99

ISBN 9780141977188 and 7195 (e-book)

Published 30 April 2015

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Send her victorious

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login