This book is a true banquet, a lavish succession of courses making up a real blowout of facts and references, some spicy, some less so, all served up with delicious side dishes and copious drafts of heady intellectual wine. A few readers may find the whole meal a little more filling than they might have wished, but it is certainly a major scholarly feast.

However, in spite of its title, this book is not really a history - even an intellectual history - of cannibalism. I doubt whether there could be such a thing, unless we elide the distinction between the teller of a tale and the tale told, as, indeed, one of the enthusiastic blurbs on the book appears to do. It insists that this "wonderful study treats the cannibal as a scholarly creature who animates theoretical texts", thereby conjuring up the image of a happy Polynesian or shipwrecked sailor munching on a nice bit of thigh while reading Michel Foucault or producing a video for Jacques Derrida.

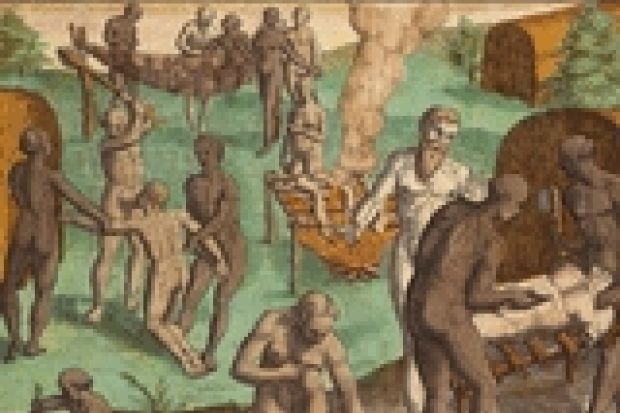

Rather, An Intellectual History of Cannibalism (translated by Alistair Ian Blyth) is a study of what philosophers and political theorists made of the facts, or stories, of cannibalism that were brought to Europe in the early modern period by more or less truthful travellers.

The figure of the cannibal entered the European imagination with the voyages of exploration made in the 16th to 18th centuries, and engaged thinkers from Michel de Montaigne and Samuel von Pufendorf through Thomas Hobbes to John Locke, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and a host of minor writers.

The cannibal attracted these thinkers' attention because of the pressure he put on various ideas about God and humanity. For example, Catalin Avramescu shows us how in the early modern period, the cannibal posed a threat to the doctrine of the resurrection of the body.

After all, it is one thing to imagine God and his angels scraping together the molecules of my dead body if they are simply scattered around the Earth, but quite another to suppose that even He could apportion the same molecule between someone to whom it once belonged and the consumer of whom it becomes a part. Unseemly squabbling on the Day of Judgment? Not a pleasant prospect.

More seriously, the phenomenon also put pressure on the doctrine of Natural Law, inscribed in all men's hearts as a set of innate moral-guidance rules, revealed by an inner "candle of the Lord" that infallibly delineates right and wrong. Blindness to what the candle showed could only be a consequence of a sin such as pride.

The happy cannibal posed a problem for this equally happy Protestantism, since his candle seemed to be quite shockingly dim or altogether extinguished. If you cannot see that eating each other is wrong, what hope is there for more refined moral manners?

But cannibalism also raised knotty problems about necessity and rights. Suppose I can only get by if I eat you, as in a shipwreck scenario. Does my necessity give me the right to do so? Or are we in a state of nature in which everyone has a right to anything, so that in effect the notion of a "right" is in abeyance and might rules instead?

If we find cannibalism disgusting, then how much of this is because we tend to know where our next meal is coming from? Is it, after all, a question of taste?

The great British legal case testing these questions was Regina v Dudley and Stephens in 1884. Cast adrift on a lifeboat 1,000 miles from land and close to death, sailors Thomas Dudley and Edward Stephens killed their cabin boy, Richard Parker, and with their shipmate Edmund Brooks survived on Parker's remains until they were rescued four days later, by which time all four would otherwise have probably perished.

Dudley and Stephens were brought to trial on their return to England, and the judges wrestled with Hugo Grotius and Pufendorf, Lord Bacon and Lord Hales, the concept of necessity, the right to self-preservation and other weighty considerations, before eventually pronouncing a verdict of guilty and imposing the death penalty. It was, however, commuted to six months' imprisonment.

Avramescu does not give us a detailed reaction to such cases. His method is eclectic, moving rapidly from one plate on the buffet to another, but he does reflect on why cannibalism has substantially vanished from the philosophical menu.

Partly, from the 18th century onwards, people became more sceptical of lurid travellers' tales about the grotesque horrors of native lands. Partly, theologians lost interest in the resurrection of the body. And partly, philosophers decided that "state of nature" political models were either useless, or if they served any purpose were little beholden to empirical fact.

But moral monsters still fascinate us. It is perhaps just chance that British and American propaganda never succeeded in tarring Adolf Hitler with the brush of being a cannibal. But I found it surprising that Hannibal Lecter and Jeffrey Dahmer, the Milwaukee serial killer, did not make it into this book's index.

An Intellectual History of Cannibalism

By Catalin Avramescu

Princeton University Press 360pp, £20.95

ISBN 97806911330

Published 19 May 2009

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login