It is clear, says Cary Cooper, distinguished professor of organisational psychology and health at Lancaster University Management School, that "academics are much more technologically and digitally savvy than ever before". Yet this often seems to lead to some curious compromises rather than a wholehearted embrace of the paperless future.

"We have the technology," notes Cooper, "but do I see paperless offices? I see printouts of emails everywhere. Nor do I see a move to make it all digital. Perhaps it's the insecurity, a lack of trust in technology. What if I take only a laptop to a meeting and it lets me down?"

Cooper believes that the reluctance to embrace progress is "less a generational issue than a question of how secure we feel about the technology. A paperless office requires you to be transportable, so it will make a big difference when we are sure that every workplace has proper wi-fiaccess."

In the meantime, he adds, it is common to go to a meeting and find "just one person there with no paper, doing it all online".

In 2007, Cooper co-authored with Theo Theobald a book titled Detox Your Desk: Declutter Your Life and Mind. Given that it is stressful to be surrounded by paper, he agrees that the decluttering ideal is "implicitly about moving to a more paperless environment". Yet in reality, he finds himself "printing out probably 50 per cent of my emails. I keep the most important online but have the lesser-priority ones sitting on my desk - if I kept everything online, I would never get back to the low-priority ones."

A management consultant could probably make a good case for going paperless. But although some academics are enthusiastically moving in that direction, many find themselves sabotaged by colleagues stuck in the past, or discover that paper suits them better for getting their creative juices flowing or other personal reasons. And then, of course, there are the old-time literary scholars who wax lyrical about humanist typefaces and the delights of uterine vellum. Surely no one is ever going to be able to wean them off their addiction to paper?

A straw poll of what is happening in UK universities gives a sense of the paperless revolution not quite arriving. It also throws up some surprises.

At 28, Richard Medcalf, lecturer in sport and leisure at the University of Wolverhampton, feels that he has been very influenced by the culture of the three different institutions where he has worked in his career so far. When employed in further education, he was required to embrace "the idea of accountability which comes with paper". A move to a university and the demands of "the sustainability and cost-cutting agenda" have led to a decisive shift.

"We are moving online in administration and teaching," he reports. "I haven't printed out an email or any handouts in the past year. I receive far more emails than messages in my pigeonhole."

Although online marking is still new to him and takes him longer while he is getting used to it, he acknowledges that it is "more legible and practical if you've got students abroad - and the quality of feedback is probably as good".

But although 70 or 80 per cent of his work is now electronic, Medcalf does not see himself as a "passionate advocate" of paperlessness. For research projects, he explains, "I prefer to have papers in front of me to annotate. I find it tangible and tactile. For an extended piece of writing, I still cover my desk in paper."

He had even scribbled down some notes in preparation for being interviewed by Times Higher Education.

Jonathan Savage, reader in education at Manchester Metropolitan University, wishes he had a completely paperless office, despite it having "all the hangovers of other ways of working". Although "happy to do all [his] work electronically" and convinced that electronic marking generates more detailed feedback for students, he also believes that "reading in different formats is a different experience".

"Perhaps we are less receptive to electronic texts and find it harder to follow a sustained argument. I once made a resolution to read a physical book for an hour a day and found it an enjoyable relief," he says.

Even in the mid-1990s, recalls Lee Jones, lecturer in international politics at Queen Mary, University of London, PhD students were advised to use a system of file cards to store information - a working method that now seems almost unimaginably archaic to those who have been brought up reading and annotating journal articles online. Although he still finds a blank piece of paper less daunting than a blank screen for the initial planning stages of a writing project, in every other respect he has "always tried to minimise the amount of paper I use...If you took away EndNote [the bibliography software] and Word, I don't know how I would work."

Peter Matthews, lecturer in the built environment at Heriot-Watt University, has been in post for only 18 months and believes the issue is "a generational thing - I've been paperless throughout my PhD". He finds it far quicker and easier to download journal articles to his Kindle and now does about 70 per cent of his reading in that format or on screen. He is equally happy to do all his marking online and although required to print out his students' work to create a hard-copy archive, he does not really understand why.

Yet Matthews finds he cannot prevent the paper piling up in his office, with a largely digital life sometimes leading to a neglect of the more physical kind of filing. While some of the detritus consists of material that has to be printed out, such as boarding passes, most of the rest has been sent to him by other people.

"There's a generational divide," he concludes, "which leads to paper processes continuing."

Rather paradoxically, it is an academic expert on the history of the book who turns out to take the most uncompromising line, utterly rejecting the "sentimental and unhelpful attachment to paper" common among literary scholars in favour of a totally paperless life.

"Ever since I was a student, I have found paper the most awkward possible medium," recalls Gabriel Egan, who has just taken up a post as professor of Shakespeare studies at De Montfort University. "Hard-copy books are never in the right place. But now I can have 3,500 titles - including everything I have written and read since I was an undergraduate - with me in one place at all times.

"I am completely paperless now and finally got rid of all my books seven years ago. When I do get a book, I usually destroy it by scanning it in. I just tear the covers off, slice away the glued binding with a guillotine and put the pages into a hopper, so the complete text is turned into a single PDF. It only takes about five minutes or so."

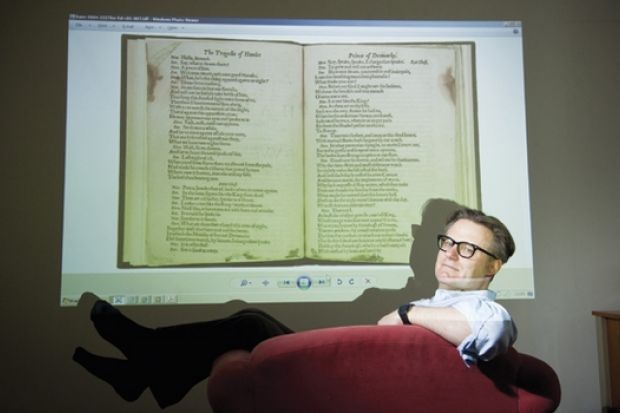

While the arguments for reading in fully searchable digital formats are familiar, Egan's particular solution is not. Both at home and at work, he uses a cheap data projector to display text on a plain painted wall 10ft-15ft away, which he claims allows his middle-aged eyes "to read for up to 12 hours without strain or any ill effects". He does not even need a desk, but lies back on a sofa with his feet up. An ergonomic keyboard held on his lap with his arms relaxed is all he needs for typing.

Since he works on early printing and even topics such as stop-press corrections in Shakespeare, Egan does have occasion to go to rare book libraries and has personally handled six of the seven surviving first editions of Hamlet. Yet he stresses that the only thrill he got from this was purely intellectually and "nothing to do with a sentimental and unhelpful attachment to paper. I strongly dislike the fetishism of the book some scholars go in for, which I see as immature and harmful to the research."

But is there no contradiction between a deep interest in printing and the almost savage contempt with which he treats any new books that happen to come his way?

Not at all, argues Egan. "I am interested in the latest literary technology. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the book was new and had important effects, so I look at how it altered and enhanced thinking. I'm not interested in the long period after that, when the technology of books was not essentially changing." Now that we are witnessing another major technological shift, it deserves to be examined and embraced without nostalgia or sentimentality, he says.

Although personally delighted to receive and return student essays electronically, Egan has observed "a friction between camps and reluctance to break away from paper, especially in English departments". It was this that led his former employer, Loughborough University, to introduce a requirement for "dual submission" of an essay in paper and digital format, accompanied by a promise that the two texts were exactly the same. Many students were "furious" that they had to print out and come in to the university to deliver material that was then often read online, he says.

But can even such a passionate advocate of the paperless house and office really manage without books altogether?

"I've got a few books lying around at home for reading in bed," Egan admits. "That's the last bastion."

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login