The proposal - for additional immigration data exclusive of university students to be established alongside present figures - could also protect the academy from any further toughening of student-visa rules.

Edward Acton, vice-chancellor of the University of East Anglia and chair of UUK's task force on the Tier 4 student-visa system, said: "This move we're proposing would make it far easier for universities and the British Council to get the message across...that legitimate non-European Union students are most welcome."

At present, overseas students are included in net migration figures published by the Office for National Statistics. The government has pledged to reduce this count to the "tens of thousands" by 2015. But in 2010, net migration to the UK was 252,000 - the highest on record.

Of 591,000 immigrants, 238,000 arrived to study at universities, schools and colleges.

Tighter rules on student visas, a major focus for the government, were introduced in 2011. The changes are hitting UK universities just as one major competitor nation, Australia, eases its visa regime for overseas students.

Colin Riordan, vice-chancellor of the University of Essex, highlighted "substantial drops" in Indian applicants for 2012 entry at many UK universities when he spoke at the Improving the International Student Experience conference in London last week.

"The argument we've got to make is about net migration itself," he said. "Yes, we accept that the government has a commitment in this area; that there is political pressure from constituents, from voters. But there must be a recognition that students are not migrants: they come here, they study and they go home."

Referring to the record net migration figures, Professor Riordan said it was "quite difficult to see any other way the government is going to achieve its aim".

A count exclusive of international students could be "a way forward that will allow the government to achieve its aims and [us to] achieve our aim, which is to educate students and transform their futures", he added.

UUK said the focus would be on non-EU students as those from the EU are not subject to immigration controls.

Professor Acton told Times Higher Education that "public concern about immigration" needed to be balanced against the economic benefits of the UK's "stunning international competitive advantage" in the global higher education market.

"While the net migration figure is far above the government's target, there is a risk that further changes to Tier 4 would be broadcast internationally as Britain not being welcoming to international students...from outside the EU," he added.

Professor Acton said that while retaining its previous dataset, the ONS could establish "an additional line of information" for foreign student numbers, meaning that "nobody can say that the government is obscuring progress towards its target as originally defined".

The new count would not "on its own" lower net migration to the tens of thousands, he added.

But the proposal was given short shrift by the Home Office. A spokeswoman said: "We are taking action to control migration and restore public confidence, which will not be achieved by fiddling the statistics."

The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, seen as a stronger advocate for the economic benefits of international higher education, declined to comment.

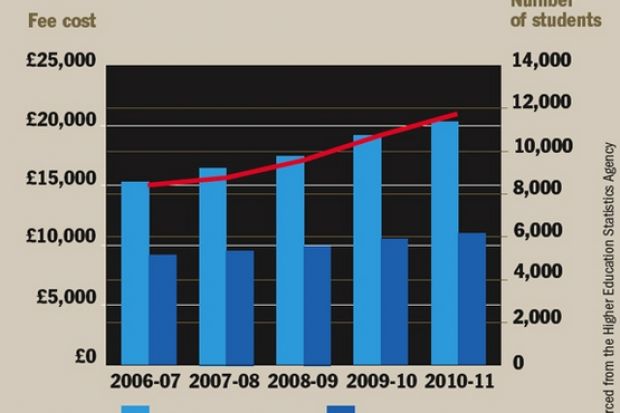

Up, up and away: overseas student numbers and fees rise

The number of international students at UK universities has risen by 35 per cent over the past five years, and has more than doubled since 2000-01, according to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

The total now stands at over 298,000. Despite this, the proportion from outside the European Union compared with domestic and EU students has remained fairly constant, rising from 10 per cent to 12 per cent in five years.

The largest group of overseas students comes from China, which has accounted for about a fifth of total numbers since 2006-07.

There has been growth in the numbers from India, up from 10 per cent of total numbers in 2006-07 to 14 per cent in 2009-10. Saudi Arabian and Nigerian student numbers have also risen significantly.

The graph below plots the upward trend in full-time undergraduate non-EU student numbers in the UK over the past five years. As the numbers have increased, so has the average fee: the University of Oxford charged the most between 2006 and 2007, with Imperial College London taking over in subsequent years.

sarah.cunnane@tsleducation.com

To exploit burgeoning markets in emerging economies, the UK must adhere to the rules of attraction

International income generated by UK higher education is expected to double by 2025 as new markets for overseas students open up, Universities UK believes.

Export earnings from universities and colleges will rise from £8.4 billion in 2010 to £16.9 billion in 2025 in real terms, according to a UUK report, Higher Education - Meeting the Challenges of the 21st Century, published on 26 January.

Most of the income will derive from tuition fees paid by overseas students and their off-campus spending, although about one-fifth will come from other activities, including research, consultancy and courses taught overseas but validated by UK institutions.

The emerging Bric knowledge economies (Brazil, Russia, India and China) are likely to be key sources of growth in overseas student numbers, alongside other "middle-income" nations.

Projections by the World Bank indicate that the "global middle class", swelled by millions from the emerging economies, will number more than 1 billion by 2030.

But the predicted growth of the UK sector's income is dependent on a "favourable policy environment", the report warns, which includes "policies to promote the attractiveness of the UK as a destination for top international students and [to] ensure the smooth flow of students into the system". In a direct warning about current immigration policy, it adds: "Imposing restrictions on student visas, for example, will severely restrict the growth of this market."

Paul O'Prey, vice-chancellor of the University of Roehampton and chair of UUK's longer-term strategy network, which compiled the report, said: "Universities are very powerful engines for economic growth and we need to be sure we keep our competitive edge in a fast-changing world. That would be put [under] serious threat if the attractiveness of the UK as a destination is threatened."

The UUK report came as a separate study by the government, Tracking International Graduate Outcomes 2011, suggested that foreign students at UK universities had better job prospects than those who stayed at home.

The report claims that 95 per cent of international students who graduated in 2008 were in full-time employment after three years, 83 per cent felt their degree was a worthwhile financial investment and 91 per cent were satisfied with their learning experience.

However, Carl Levy, reader in European politics at Goldsmiths, University of London, observed that migrants were, throughout history, more ambitious and therefore likely to earn more money than those less willing or able to travel abroad.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login