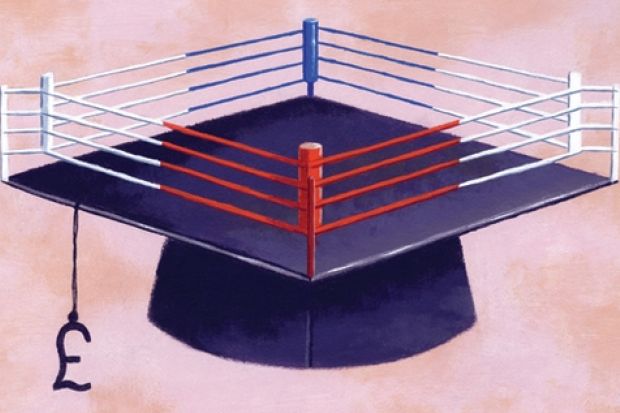

The University of Cambridge will charge undergraduate tuition fees of £9,000 a year, and the University of Oxford appears set to follow suit. Just as Rolls-Royce charges high prices almost by design, so our elite universities were always destined to do so.

More worrying is that every other university may do so, too. Les Ebdon, vice-chancellor of the University of Bedfordshire, thinks all institutions will charge £9,000 within two years, and Sir Peter Scott, former vice-chancellor of Kingston University and currently professor of higher education studies at the Institute of Education, concurs.

Scott argued in these pages in December 2010 that universities "need the money" and that the difference between (say) £7,000 and £9,000 is too small to change student behaviour, given that they will not pay the money up front.

It doesn't have to be this way. The contact hours for many arts and humanities students are - to outsiders - surprisingly short. Furthermore, universities offer huge economies of scale compared with schools, since lectures can contain hundreds of people. In addition, many classes are given by postgraduates or other relatively low-paid ad hoc staff.

It is not clear why university fees have to be higher per hour of tuition than those of good private schools. If we take St Paul's Girls' School - which offers students 40 periods per week in their first year and charges £5,434 a term - as a benchmark, then a typical degree should cost £4,350 a year; if we use Bradford Grammar School as a yardstick, the fee should be £2,600. If the government gets the system right, most undergraduates will pay fees at levels like these. BPP University College is charging £3,225 a year for its degree in business studies, so it can be done.

We know how to get prices down: introduce competition and allow new entrants. This has worked in (almost) every sector of the economy. The coalition has allowed new entry, and students should welcome BPP's emphasis on price. But these entrants are likely to be too small to affect the sector's overall dynamics: rather like free schools, they will introduce competition only at the margins, and most incumbents will be able to ignore them.

Universities appear to compete for students, but in reality the Higher Education Funding Council for England divides potential students across the sector via quotas. So a university will get its students almost irrespective of what it charges and how unpopular it is.

There is talk of reducing the guarantee to 90 per cent of the quota, but what firm would seek efficiencies with enthusiasm if guaranteed 90 per cent of its market share? None.

The government's thinking will lead to almost all universities charging £9,000 for almost all courses. That is bad for students and bad for taxpayers, since between a quarter and a half of graduates will not repay their debts to the government.

The only form of competition that will work for students and taxpayers is one that allows existing players to expand dramatically if they are successful - and holds out the prospect of bankruptcy for those that aren't. That is the discipline under which every firm in a free market operates. This is perfectly compatible with good education, as the private school system proves.

In introducing competition, the government cannot simply allow popular universities to expand, since students are subsidised via the contingent loan system and overall expansion is therefore costly. Instead, it needs to force institutions to compete for the right to offer places. From Student Loans Company data, the coalition already knows the income profile of students at different universities studying different courses. It can predict the likely losses from different graduates.

The losses from Oxford and Cambridge graduates are likely to be low, even with fees of £9,000 plus maintenance grants, because they generally go on to well-paid careers. The government can be more relaxed about high fees there than among students whose pre-university qualifications, university of choice and subject do not predict Oxbridge graduate salaries. Here the state needs to be more aggressive in playing institutions against each other and new entrants to force fees down.

A formal auction mechanism, with no guaranteed quota, is most likely to persuade universities to offer fees that work for students and state. Those that bid too high will simply not be allowed to offer places. That will concentrate minds.

Not all universities can offer degrees for £4,650, and certainly not in every subject. Pay rates at top research universities are higher than at top private schools. Lawyers, economists and the like are expensive. But many universities could offer good degrees for less than £6,000. Competition will force them to do so, and the government must introduce it, for the sake of students and taxpayers alike.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login