The decision to virtually eliminate public funding for university teaching in England appears to imply that the benefits of studying for a degree are almost entirely private.

But a campaign calling for recognition of the public value of higher study is gathering momentum, with academics from across the globe challenging the fundamental shift in university funding.

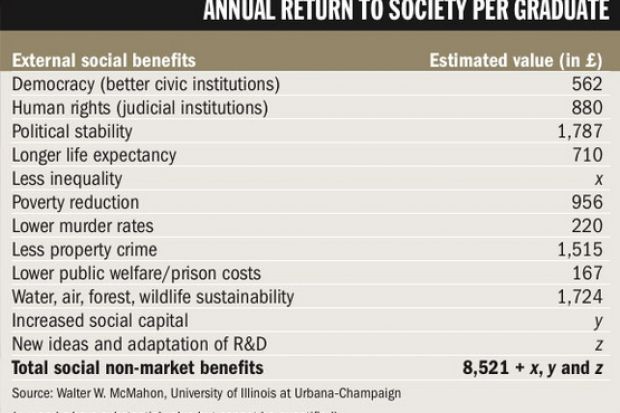

At the Universities and their Regional Impacts: Making a Difference to the Economy and Society conference in Edinburgh last week, Walter W. McMahon, a US economist who has put a monetary value on the wider social benefits of higher education (see table below), warned the UK against the "worrisome" move.

Professor McMahon, author of Higher Learning, Greater Good: The Private and Social Benefits of Higher Education (2009), has studied the "private non-market benefits" for individuals of having degrees, including better personal health and improved cognitive development in their children, alongside the "social non-market benefits", such as lower spending on prisons and greater political stability.

The professor emeritus of economics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign said that while there are benefits to increased private contributions to university education, the wider social benefits of higher study mean that the state should continue to invest in teaching.

Under current proposals for the future funding of higher education in England, all public support would be removed from courses in arts, humanities and social science disciplines, to be replaced by higher student-tuition fees.

Teaching funding would be cut by as much as 80 per cent.

"You need to be very much on guard," Professor McMahon said. "There's a danger. The social benefits of higher education are considerable. The individual or family does not have the incentive to invest to benefit future generations. Society has to do some investing."

Meanwhile, a group of academics including Gurminder Bhambra, director of the Social Theory Centre at the University of Warwick, and John Holmwood, professor of sociology at the University of Nottingham, has launched the Campaign for the Public University.

It is urging academics to write to the vice-chancellors of Russell Group institutions in protest at their silence over the cuts.

"We have organised the campaign because we are shocked that the privatisation of higher education and its subordination to the market is being introduced without proper discussion and debate of the likely consequences for public life," the organisers write.

In a similar vein, Roger Brown, professor of higher education policy at Liverpool Hope University, was set to argue at a conference on 24 November that a healthy higher education system requires a balance between public and private sources of funding.

He was expected to warn that the government's proposals would leave British universities with the same level of public funding as Chile.

"It is well established in the literature that higher education provides a range of public and private benefits, and that these are both economic and social in character," he was due to say at the University and College Union and National Union of Students event in London, Universities in the 21st Century.

Public benefits include increased tax revenues, greater productivity, reduced crime rates, increased charitable giving and social cohesion.

"Recognition of the need for a balance between public and private benefits and costs is obviously missing from the Browne Review," Professor Brown was due to say.

"On this and on so many other matters, the committee shows an extraordinary degree of illiteracy. The two vice-chancellors involved (David Eastwood of the University of Birmingham and Julia King of Aston University) should be ashamed to be associated with such a document."

Professor McMahon said that cutting back public support for higher education tended to lead to the "vocationalisation" of degree courses, with increased reliance on "nose to the grindstone, job-oriented courses".

He argued that in the face of public funding cuts in the US and UK, "the best defence is offence. We need to sell the product."

On the question of how far privatisation should go, he said that between 54 and 69 per cent of the benefits of higher education qualifications in the UK were private, both market and non-market, so individual contributions should reflect that.

rebecca.attwood@tsleducation.com

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login