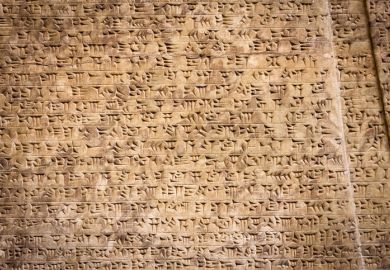

The Greeks and Greek Love will be read by many people, and I predict a riot. For the past 25 years, studies of Greek sex have been dominated by the unholy partnership of the bald Michel Foucault and the pigeon-chested Kenneth Dover. They drew up a model of male sexuality, based largely on the philosophical and rhetorical tradition, that emphasised that ancient sexual behaviour was not defined by sexual object but by power relations. The dominant male partner took pleasure - with long courtship and many restrictions and provisos - and the passive partner reciprocated with respect at best. In this history, "homosexuality", in the sense of the medical and psychological definition of a person according to whom he has sex with, is a 19th-century invention. As the US theorist David Halperin puts it, there have been only 100 years of homosexuality.

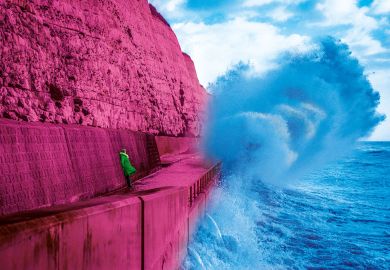

James Davidson sets out to offer a radical reappraisal of this constructivist model, which he calls "sodomania" - an obsession with penetration and power. In its place, he emphasises loving partnerships of men, founded on the flash of passionate desire of an older man for a younger man, which he calls, rather wonderfully, "homobesottedness". He sees the bonded pairing of men as a pervasive model not just in social life but also in the imaginative worlds of myth, literature and art. At the centre of this book is an image of the greatest hero of the Greeks, Achilles, binding the wound of his dearest companion Patroclus: two strong men, significantly on their own, locked in an act of care and affection.

There are long sections in this long book of real brilliance, and it is written throughout with flair and passion. I finished it exhausted but keen to discuss many readings and claims with the author and other pals. Davidson is clearly right to look carefully at how different cities constructed different models of male sexuality, and used other cities to define themselves. He is extremely sharp at separating mere sexual activity from the cultural discourse of "Greek love": he knows that finding evidence of a quickie behind the gym does not challenge the power of social expectation. His emphasis on the potential for caring and bonding in male relations is a necessary nuancing rather than a radical challenge to our understanding of the lack of reciprocity expected in sexual pleasure in Greek culture. It is smart to underline the importance of the question, "For what reason did sex take place?", rather than "How was it done?" His critique of Dover is especially piquant: he brings out the sheer oddity of Dover's thoughts on sexuality with a cunning that will enrage Dover's supporters and amuse his enemies.

But it is a pity that the radical and sensible in this book may be swamped by shrill criticisms of the perverse, the silly and the over the top. "You think I am getting carried away?" Davidson writes paradigmatically. "I don't." Many will. That disarming remark, for example, is made apropos of the claim that the white of the bandages with which Achilles wraps Patroclus should remind us of the white of ejaculated sperm. There will inevitably be howls of surprise at the claim that Alcman's first Partheneion may be a song for an institutionalised lesbian marriage; or that Orestes and Pylades are an exemplary gay couple. The very selective bibliography will annoy people who are annoyed by such things.

But for me the biggest worries are at the grandest scale of argumentation. It will not do to look at Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad without also recognising that the word that Davidson translates as love - "philotes" - is the term used for the bonds between Achilles and all the other Greeks: it implies mutual ties of reciprocal duty, and Homer is concerned with the relations of power, aggression and social need rather than with a gay couple. To make Heracles the exemplar of "gay myth" represses his rapacious encounters with women - 100 in one night; and to make Heracles's relation to Iolaus his central story begs too many questions. Davidson's spunky search for the "homosexual couple" in ancient Greece challenges many contemporary academic orthodoxies, but there are too many blinkers and special pleadings on the way.

The Greeks and Greek Love: A Radical Reappraisal of Homosexuality in Ancient Greece

By James Davidson

Weidenfeld and Nicholson

656pp

£30.00

ISBN 97802978199974

Published 29 November 2007

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login