"Danger", the radical Romantic essayist William Hazlitt wrote, is a good teacher and makes apt scholars. So are disgrace, defeat, exposure to immediate scorn and laughter. There is no opportunity in such cases for self-delusion, no idling time away, no being off your guard - neither is there room for humour or caprice or prejudice."

Tom Paulin is never off his guard. He keeps his fists up and deals with Hazlitt on his own terms. The Day-Star of Liberty is not a study of liberty and literature; it is a critic combating a critic: a muscular critic writing a muscular critique of a muscular critic.

Near the beginning of this remarkable book, Paulin briefly pauses to consider his relationship with Hazlitt: "Over the five years I've been studying Hazlitt, the wish for some glimpse of the driven, fallible, human being who created such ecstatically definite prose has prompted me to consider how piety must be part of the inspiration behind the attempt to write about a neglected author." The thought comes to Paulin as he hunts for physical traces of Hazlitt - anything with the authentic tang of his subject.

But piety? Is this religious devotion, or something closer to Hazlitt's own "piety"? For Hazlitt, who trained as a Unitarian minister, divorced twice and engaged in a thwarted affair with his landlord's daughter, Sarah Walker, "piety" clearly meant something else - if anything the study of human nature and the realisation of human potential through social and political reform and adversarial journalism. But over some 400 seamless pages, Paulin withdraws from Hazlitt's loves and life and politics and focuses instead on the physical traces within the knotty prose of his essays, a physique that drives forward his reflections on Romantic poetry, politics and power.

As such, it is a tour de force. Hazlitt is constituted by his writing. This is not a new idea - Virginia Woolf remarked that Hazlitt's essays are like fragments broken off from "some larger book" - but Paulin shows how Hazlitt's works comprise a "disjointed epic autobiography - a kind of prose Prelude". Hazlitt's essays are disjecta membra; they are like the limbs and organs of a body, they thrive only in the company of their fellows; together they animate Hazlitt (and exercise Paulin). And Paulin takes the pulse of this Hazlitt. He charts the currents of symbolism that bind Hazlitt's works together. He traces the anatomy of Hazlitt's imagination, the topography of his mind.

The breath of inspiration here is gusto (a critical term relished by Hazlitt, and by Paulin on Hazlitt). Hazlitt's essays read like a perpetual affirmation of the self against some swift, ever-threatening enemy - like the twang of the bow or a knock-down punch. He writes muscular criticism for iron men. He is keen on sports and sporting metaphors, particularly boxing, but also football and racket-ball, at which he excelled.

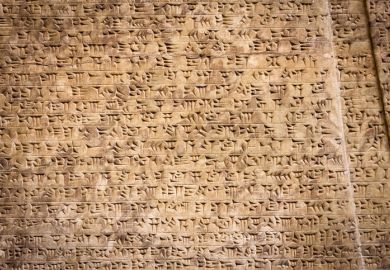

There is, it seems, a whole cult of body-building in Hazlitt. He was entranced by the Elgin Marbles: "Let anyone look at the leg of the Ilissos or River-God, which is bent under him - let him observe the swell and undulation of the calf, the intertexture of the muscles, the distinction and union of all the parts, and the effect of action everywhere impressed on the external form, as if the very marble were a flexible substance, and contained the various springs of life and motion within itself, and he will own that art and nature are here the same thing."

It is not, as Paulin notes, the nightingale or urn, nor the gothic castle or daemonic figure, but the headless, limbless body of a muscular divinity that inspires this writer: for Hazlitt, the tumble of thew and sinew across the Elgin Marbles form a "harmonious, flowing, varied prose". Like a conversation, they appeal to Hazlitt's preference for broken fragments and work-in-progress and prose, over the holistic mode of poetry. Paulin's skill is in unwinding these torn sheets of metaphor: showing how the unfinished, fractured and kinetic qualities of these marbles fall into the same patterns as Hazlitt's fascination with visual spectacles and pre-cinematic moving images, such as magic lantern shows, or with images of molten glass being blown and pancakes taking shape as symbols of writing to the moment.

Paulin also plots patterns of alliteration and assonance, and even scans some sentences. This is a brave renewal of formalist criticism as a magnificently sustained pitch of intense close reading, displaying a sharp sensitivity to fleeting effect. The rigour of Paulin's performance is uncommonly consistent and lapses only once with a becalmed interlude on structuralist bricolage. But background and context are often lean and, although Paulin is often good on the political context of revolution, current issues are dodged.

However, my biggest disagreement is with the curt treatment of Hazlitt's mad, semi-autobiographical study of sexual obsession, Liber Amoris. For Paulin, this is politically suspect stuff, parroting the language of aristocratic libertinism and articulating "a nihilistic, self-flagellating desperationI a masturbatory, taut flaccidityI an exploration of imaginative extremity which never in all its sequence of dead surprises achieves an authentic image or cadence even for a moment".

In other words, Paulin is shutting his doors against psycho-biographical criticism. Moreover the confessional mode, the idolatrous worship of Hazlitt's young paramour Sarah Walker, even the grotesque plot to test her virginity, shows Hazlitt dangerously close to an overwrought catholicism. And there are also gender issues here, of a pugilist enfeebled by coquettish flirtation. Nevertheless, Hazlitt's "Book of Love" is a howl of terrible despair and fury, as keenly felt as any of his political papers, and a pathetically courageous cry.

Paulin's Hazlitt, we begin to realise, appeals to Paulin on various fronts. He is half-Irish and therefore becomes a figure in Paulin's pantheon of vigorous, Protestant Irishmen. Moreover, he features in "a particular dissenting counter-culture". And the voice of this counter-culture is - characteristically again for Paulin - in the rugged writing that comes from the voice in the pulpit: speech and writing tied to the body, the stronger the better. Paulin too peppers his account with oral inflections, contractions and asides.

Despite these hints, immediate political implications remain dim echoes. Only in Paulin's sustained account of Hazlitt's vehement engagement with Burke do literature and politics fully overlap in the politics of expression. The echoes magnify into reverberations: "Contemplate the contradictions that tear through Burke's style, and you see the next two centuries of Irish history impatient to be born (as I write, a Sinn Fein leader is walking down the steps outside Stormont)." It is a sudden and dramatic reminder of the work of the writer and the dangers of criticism.

Nick Groom is lecturer in English, University of Exeter.

The Day-Star of Liberty: William Hazlitt's Radical Style

Author - Tom Paulin

ISBN - 0 571 17421 3

Publisher - Faber

Price - £20.00

Pages - 382

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login