Valentine Cunningham searches life and art for the real William Shakespeare.

Who is Shakespeare? For his own time, for now? Old questions, but still the current ones. The biographer Park Honan and the critic Harold Bloom prove the continuing life of these issues. As approachers to the Shakespeare meanings they could not be more different, but all the time their distinctive efforts keep converging on similar problems of knowing who exactly is Shakespeare the man and what is Shakespeare the work for and about? The sheer confusion and ambiguities of the records are emblems of the richness of the difficulty hereabouts as well as being what entices investigation.

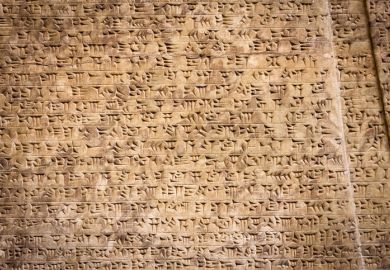

Who was Shakespeare? William Shakeshafte works for the drama-enthusiastic Catholic Hoghton family up in Lancashire. Willelmus Shaxpere is licensed by Worcester consistory court to marry Anna Whateley of Temple Grafton. William Shagspeare marries Anne "hathwey" of Stratford. Shaxberd's Measure for Measure is performed on St Stephen's Night, December 26 1604. Disgruntled Robert Greene decries an upstart stealer of other men's lines by the name of Shakescene. Gray's Inn students joke at their Christmas revels about a Shagbag who is taking London over. Egregious Will Kempe, history's unfunniest comic, calls all his enemies Shakerags. Shakerags, Shakeshafte, Shagbag, Shaxberd, Shaxpere, Shagspere, Shakescene: is Shakespeare all of these? Some of these? Who on earth is he?

One answer, it seems, is Hand D, what Honan describes as the fast-running, breathless script surviving anonymously on three folio pages of The Booke of Sir Thomas More : Quick Hand D, the Cool Hand Luke of Elizabethan palaeography, his identity fleeting words on a page, fluently set down, unrestrained, economic. The fluency should not surprise us. Hand D is one who dithers "over names, abbreviations, and other incidentals" - which seems apt as well.

Honan's glosses on Hand D - that shedding of sharp light on scripted anonymity - have an appeal and authority that are characteristic of Shakespeare: A Life . And this is undoubtedly the best assemblage so far of the historical bits and interpretative bobs that we must think of as "Shakespeare" the man: that thing of shreds and patches, the Shakespeherian rag-bag. Shakerags.

At one point in his most thorough and convincing, as well as extremely attractively written, piece of intense biographical bricolage, Honan enthuses about Falstaff as "the only being through whom the Poet of the Sonnets might speak the truth": he "symbolises nothing exactly because he expresses so many meanings". Being nothing exactly but expressing so many meanings: it is a rich idea, decidedly close to the (post) modernist notion of the text as a dense multivalent emptiness, a potent space waiting to be filled with the meanings of multiplied readers. It is also, of course, a formula for the biographical quest, for the enterprise Honan is deft in pursuing, the making of a whole Shakespeare out of the bittiness of all the available Shakerags. In yet another sense, it should remind us of the late Iris Murdoch's exalted vision of the great novelist (in which category she included Shakespeare as primus inter pares ), the man who, nothing himself, allows others to be through him. Which is where High Bardolater Harold Bloom comes in.

Bloom's strident Bard-idolising would baulk at the idea that any Shakespeare character might "symbolise nothing exactly" - for Bloom, Shakespeare's people come "rammed" with pretty exact meanings - but his great theme is still the utterly rich potentials of meaning packed into the characters of Shakespeare for all future comers. Shakespeare, Bloom contends, is for ever and ever Our Contemporary. Shakespeare has given all of us all of our humanity. Shakespeare invented us, our sense of our selves, our notions of the possibilities for personality, gave us selfhood.

Shakespeare, Bloom claims, inaugurated personality "as we have come to recognise it". The western idea of "character, of the self as a moral agent" comes from many sources - Greek, Jewish, Christian, Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Sophocles, the Bible, St Augustine, Kant - but "Personality, in our sense, is a Shakespeare invention, and is not only Shakespeare's greatest originality but also the authentic cause of his perpetual pervasiveness. Insofar as we ourselves value, and deplore, our own personalities, we are the heirs of Falstaff and of Hamlet, and of all the other persons through Shakespeare's theater of what might be called the colors of the spirit." Shakespeare's great gift to us is our sense of what inwardness is. And Bloom is greatly incited by Hegel's idea that Shakespeare's people are "free artists of themselves" (and so teach us how to be free self-makers likewise). So, we cannot "conceive of ourselves without" Shakespeare. This is his awesomeness.

Actually, it soon turns out to be Bloom's real case that we are the heirs of only a small core list of characters. Rosalind, Shylock, Iago, Lear, Macbeth, Cleopatra and, above all, Falstaff and Hamlet; these are the ones "truly endless to meditation". Even so, it seems to me that this argument for the force of Shakespeare's plays as consisting of the force of his characters - Bloom's repeated insistence that the tradition of responding to Shakespeare as the provider of stories of selfhood, visions of the person, of the character (ie the tradition of Christian moralist Dr Johnson and of A. C. Bradley, the closet reader of Shakespeare, notoriously treating the plays as if they were Victorian novels), the High Romantic and post-Romantic tradition of Coleridge and Goethe, of Hegel, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche (and Freud), of those readers who found in Shakespeare's people mirrors, and models and allegories of the self, their own and other people's - that this argument is not just vigorously put but is really impressive.

It is impressive despite the constant sneering and sniping at new-historicists and cultural materialists and all the other ideologues who are, Bloom thinks, demeaning the main selfhood issues in Shakespeare. (And, to be sure, there are still critics who do not believe in selves or persons or the human - an "elitist secular heresy" this, Bloom thinks with some cogency, though there are not as many unbelievers, I fancy, as Bloom's nightmares tell him.) It is impressive above all because of Bloom's constant personal testimony, his laying bare of his affective and intellectual self in his many stories - boasts even - of how he has been utterly moved by Shakespeare's people, in his own reading, at performances, in reading other people's readings. He keeps recalling Ralph Richardson's Falstaff, memorably witnessed when he was in his teens. He has long had a "passion" for Rosalind. He shudders at Malvolio's self-deception - "Can we hear this, or read this, without to some degree becoming Malvolio?" "It is we who are Hamlet".

And of course Bloom is right about the "infinite reverberations" of Hamlet, the way Hamlet generated a sense of self for centuries of poets and other readers, for a whole culture, in fact. The same, however, cannot be said of his favourite Falstaff, nor of his desired Rosalind and Cleopatra. The world has been greatly fond of Fat Jack, but how many of us want to be him? Bloom's adolescent-type pash for Rosalind and his notes about Cleopatra's realisations of her love in the absence through death of Antony, read more as personal affections, neuroses, fears of Harold Bloom than of anything approaching the "universal".

Far more convincing is Bloom's constant interest in the Shakespearian sense of negativity in the human lot - the melancholy of Hamlet, the anguish of Lear, the constant approach in the great tragedies to the Gnostic kenoma , emptying, vastation, "Nothing", the heart of darkness at the core of the inwardness of Hamlet, Lear, Othello, Shylock. And in this area of magnificent despairing nothing could, I think, be more moving than Bloom's notings of the dread and pain he feels with Dr Johnson at the cosmic negations of Lear , his kept-up sympathy with Shakespeare's strong line in elegiacs, the pervasive sense in the writing of the immanence of death. This is an old critic's approach to the Shakespearian purpose, of course, but all the more compelling for its personal feltness.

All of which receptivity is most dependent, one has to observe, on the kind of researches Honan pursues, and which Bloom tends to huff and puff against. No need, he keeps telling us, to be interested in Shakespeare's religion or his politics, no need to go rooting for historical and biographical causations. But at the same time he plunders such researches - and generally rather old ones - with opportunistic abandon. The traumatising death of Hamnett; Shakespeare's possible death after a drinking bout at Stratford with Jonson and Drayton (rightly dismissed by Honan, but useful to Bloom's picture of a very unretiring retired poet); the case for the Ur- Hamlet being by Shakespeare not Kyd (not entertained by Honan, and not necessary, either, to Bloom's argument about Hamlet's centrality): in all such asseverations, Bloom needs the buttresses that biographers and historians provide him. And it is clear that Bloom - or at least his six research assistants - not only might read Honan for their profit, but need to.

In fact, none of us will be able from now on to make do without Honan. He really has given us the latest word on Shakespeare's life - utterly knowledgeable, scrupulous in weighing the evidence, canny in conclusion. Stratford politics; the entrepreneurial endeavours of the glove-making father; the nature and impact of the grammar-schoolboy's grammatic training; the dense recusant web of Shakespeare's Roman Catholic relatives, teachers, associates; his married life; his actor-manager, playwright, theatre-owner existence; day-to-day realities in the world of London theatre production, practice, attendance; the parallel doings of Marlowe and Kyd and Greene and their like; the vastly influential force of plague on city, country, theatre-going (nice to learn plague-carrying fleas disliked the smell of the nuts people chomped at the play); Shakespeare's bisexuality, his dealings with Southampton, his properties, his money affairs, his will, what happened to his children: they are all here, and richly, lucidly arrayed as never before. For my money Honan makes as good an introduction to Shakespeare's life and times and work, and as good an advert for scholarly biography, as anyone could wish. He does, I think, make a bit too much of the grammar-school heritage, and he does, naturally have to resort to the usual maybes and perhapses that stud all Shakespeare lives; but for astute biography and biographical criticism (read with joy those pages about Bottom's wall and the saga of Stratford's recalcitrant wall-repairers), Honan is your only man. Not as awesomely boisterous as loud Harold; but so much the better for that.

Valentine Cunningham is professor of English, University of Oxford.

Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human

Author - Harold Bloom

ISBN - 1 84115 047 9

Publisher - Fourth Estate

Price - £25.00

Pages - 745

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login