UK universities are shifting attention from their traditional role of educating home students towards private and international provision, according to a survey of vice-chancellors and administrative heads.

The Quiet Revolution: How Strategic Partnerships and Alliances are Reshaping the Higher Education System, a report by PA Consulting Group, has found that 42 per cent of institutions have "substantial" arrangements with private education companies.

Mike Boxall, co-author of the report, said that while universities were not looking to "walk away from public higher education", they were concentrating their business development on international activity and private education.

"What's happening is that universities are quietly getting on with new partnerships that are allowing them to grow their non-traditional business," he said.

Almost three-quarters of respondents say that their institution has relationships with industry or commercial organisations that will transform the "direction, revenues or operations" of the university and its partners.

Eighty-eight per cent have similar alliances with overseas institutions.

Mr Boxall explained that commercial arrangements could include the type set up with firms such as INTO University Partnerships or the Cambridge Education Group, which feed international students on to undergraduate programmes following preparatory courses run by the companies.

Other institutions had struck joint research deals with firms and were designing courses together, he said.

Another option was to have companies sponsor students through university, circumventing caps on undergraduate numbers, Mr Boxall explained. For example, the auditing firm KPMG runs a programme where it funds school leavers to complete accountancy courses at Durham University and the University of Exeter.

The report also reveals that while 87 per cent of respondents in 2011 believed that private providers would pose "significant competition", this year the figure is 72 per cent.

"Private providers haven't [grown] as fast or [been] as detrimental to the...traditional players as they thought," Mr Boxall said.

Paul Woodgates, the report's other author, said that the "buying-up of failing universities" anticipated by some had not materialised.

Instead, state-funded universities were exploring what they might be able to learn from the private sector, he said. For example, 78 per cent of respondents think there will be a trend towards "no-frills" low-cost provision, a 21 percentage point increase on 2011.

The report, which is based on 95 responses, also finds that nine in 10 university leaders predict a "dramatic polarisation" of the sector between a small "super league" of research-intensive universities and a growing number of low-cost institutions.

Some respondents see the emergence of a two-tier system as an "unintended and damaging" consequence of combined government policies, the report says.

david.matthews@tsleducation.com.

Comment: how the higher education sector is collaborating with its competitors

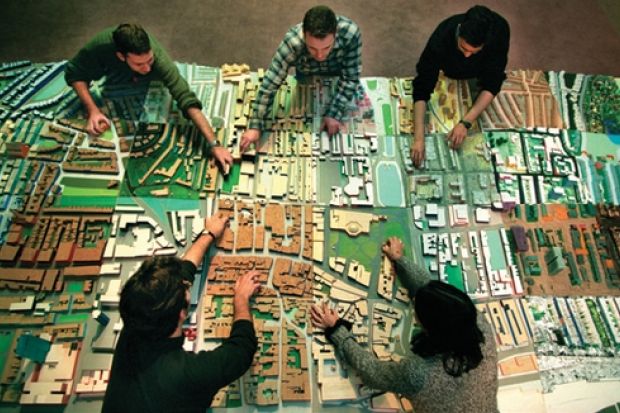

This question was first posed by Harvard professor Theodore Levitt to corporate America, to highlight how many once-dominant industries declined because their leaders failed to recognise shifts in what their markets were buying. Most higher education leaders, faced with Levitt’s question, would confidently say they are in the “university business”. By that they mean the business of institutions and communities of scholars, pushing the boundaries of knowledge and passing it on to selected students through well-defined degree programmes. Which would be fine, except that the clients and funders of 21st century universities regard themselves as being in the “learning business”. They think that they, not the universities, should have control over what, where, when and how they learn. This discord between providers and clients has led some to predict that new internet-empowered providers offering user-centred learning options will sweep away the old, universities who are unwilling to adapt. But PA Consulting Group’s latest annual survey of higher education leaders shows that, like previous predictions of the demise of universities, this scenario will almost certainly be proved wrong. In reality, the business of higher education is quietly being redrawn through alliances and partnerships between the university old guard and new learning services providers. Our survey shows that 80 per cent of higher education leaders believe multi-institutional and public-private partnerships and alliances will be a major force for reshaping the sector. All but a few institutions are already heavily engaged in at least one strategic business partnership – large scale initiatives with the potential to be game changing for both parties. Nearly half claim a polygamous array of six or more such alliances. Our survey findings revealed two factors driving this quiet revolution – the increasing difficulty for most institutions of sustaining their public higher education business (home/European Union undergraduate teaching and funded research), and the imperative to grow alternative services and markets very quickly. While a minority of institutions continues to look to publicly-funded education (including health and teaching) and research to sustain their future business, the majority (over 60 per cent) see this as a shrinking pool and are looking to secure their futures outside the publicly-regulated domain. Almost all of our respondents foresee a binary split in the higher education sector between a small super league of large, research intensive institutions who are able to secure most of the available research funding and the most academically-able students, and substantial growth in low cost, no frills providers competing at the other end of the market. The outlook for those institutions caught in the ‘squeezed middle’ of this divide is a big concern. In what some perceive as an unintended consequence of government policies, the majority of institution leaders are prioritising unregulated and international markets for their future growth. These are mainly offshore provision, private market education (such as continuing professional development and short courses) and entirely new ventures such as employer-sponsored professional development programmes. In a marked departure from the old do-it-yourself culture of universities, institutions recognise that the cheapest, quickest and safest ways to grow new business and new services are through complementary alliances with others who already have the necessary expertise, resources and market presence. The new strategic alliances are hugely diverse in their form, scope and objectives. The most common partnerships are with overseas higher education institutions, followed by tie-ups with industry or commercial organisations, government departments and agencies, other education or research providers (public and private), and business services providers. By far the strongest motivation is to meet providers’ internationalisation goals, followed by revenue growth and diversification, and new business or market development. Cost reduction and operational considerations were noticeably lower motives for strategic partnerships, perhaps reflecting the difficulties that many have encountered in shared service ventures. It is still early days for these kinds of radical partnerships, and there is an acknowledged degree of experimentation and exploration. But providers of all kinds clearly see long-term strategic alliances as defining features of the future higher education system. This may explain a paradox: each year our survey has shown a widespread expectation among sector leaders of large numbers of institutional failures and/or mergers. Yet in practice we have seen very few of either. What we are seeing instead is a ‘soft restructuring’ of the system, in which the boundaries between public and private, domestic and global organisations are pragmatically redrawn, without fanfare or the trauma of institutional failures. The sector is quietly changing the business it is in, to meet the changes in the markets it serves. Professor Levitt would be proud! Postscript: Mike Boxall and Paul Woodgates are higher education experts at PA Consulting Group.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login