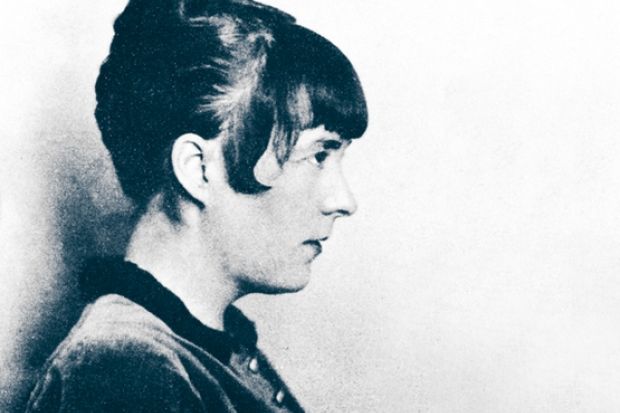

For a long time it seemed that Modernism was dead, an ogre slain by the many-headed hydra of Post-Modernism. When, in the early 1990s, I tried to get my PhD thesis on the Imagist poets published, one editor at a major press said that the proposal was well presented, but that there was not much interest in Imagist poets such as H.D. (born Hilda Doolittle) or Ezra Pound. In an effort to encourage an enthusiastic but naive young researcher, the editor sought to find something more positive to say. "We would be more interested in a book on the Post-Modernist image," she offered - so could I reshape the proposal along those lines?

I never did reshape the proposal, but these days I suspect that many humanities publishers would give short shrift to the idea of a book on the Post-Modernist image, while a new account of the first Modernist movement in English poetry would be eagerly considered. Introductions to Modernism are now de rigueur for publishers, and research monographs with "Modernism" in the title continue to proliferate.

Since 1998, four organisations have sprung up to promote the study of Modernism worldwide: the Modernist Studies Association, based in the US; the European Network for Avant-Garde and Modernism Studies; the Australian Modernist Studies Network; and the British Association for Modernist Studies (BAMS), which was formally constituted in 2010.

The establishment of the BAMS builds on pre-existing networks such as the London Modernism Seminar, the Northern Modernism Seminar and the Scottish Network of Modernist Studies. The BAMS works with such regionally based groups to foster Modernism scholarship across the country. The Scottish Network and the BAMS recently held a successful conference exploring the legacy of Virginia Woolf's claim that "on or about December 1910 human character changed". For many researchers working in humanities departments, the cry is now: Post-Modernism is dead, long live Modernism!

How have we got to the point where a movement in culture and the arts from more than a century ago that was once lambasted as monolithic, reactionary and outdated is now the subject of so much interest?

The aesthetic of Modernism that emerged in the latter half of the 19th century is part of a cultural history that can now be studied in a more detached fashion. Undergraduates used to joke that an English literature syllabus ran from Beowulf to Virginia Woolf. Woolf was seen as a more or less contemporary author, and to venture past the year of her death (1941) to consider later writing was faintly scandalous. But Modernism now feels properly historical rather than nearly contemporary: most of its major artistic figures died several decades ago.

Paradoxically, however, Modernist culture is deeply familiar to us: we live with the consequences of the major changes in technology (motor cars, telephones, television), urban life (skyscrapers) and politics (feminism, the idea of revolution) that were ushered in with Modernism and modernity.

Moreover, the commitment to stylistic innovation pioneered by Modernists continues to influence contemporary artistic practitioners. We are still within a culture of Modernism - a recent anthology of work by contemporary poets for the independent publisher Salt was subtitled "New Modernist Poems". Anish Kapoor's monumental sculpture owes more than a little to those of Constantin Brancusi. Although for some, Modernism ended with the start of the Second World War, our sense of what constitutes late Modernism now seems to get later and later.

Regardless of such questions, the expansion of what counts as Modernism has provoked a reawakening of interest in writers and artists unjustly jettisoned in the Post-Modernist craze of the 1980s. Then, exponents of Post-Modernism tended to caricature Modernism severely, and Jean-Francois Lyotard's critique of "grand narratives" was (mistakenly) interpreted as an attack on anything that could be labelled "Modernist", from art to social theory.

Modernism was a monument that needed to be exploded to open up a brave new world of difference and diversity. Although by no means a card-carrying Post-Modernist, John Carey popularised this view in his book The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880-1939, which offered an overly simplistic picture of Modernists as snobbish bigots.

From the mid-1990s, and starting with Peter Nicholls' Modernisms: A Literary Guide, much critical work has sought to redress such views by pointing to the many diverse forms of Modernisms that appeared in the early part of the 20th century and beyond. "Make it New" was Ezra Pound's slogan for Modernism, and many of the current generation of Modernist scholars follow this lead, revising completely the field of what constitutes Modernism.

The recent Oxford Handbook of Modernisms, for example, contains accounts of queer Modernism, travel writing and the writers of the Harlem Renaissance. In this volume, the geography of Modernism is expanded to include chapters on India, Africa, the Caribbean and China. Some exciting work is being done on colonial and global Modernisms, exploring how individual national cultures revise Anglo-European Modernist forms. There has also been renewed interest in Djuna Barnes, Katherine Mansfield, Dorothy Richardson and other innovative female writers. Mansfield and Richardson now have very active scholarly organisations devoted to their work. Such an expanded canon means that it is rather difficult to fit the socialist-feminist Richardson or the gay Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes (a communist sympathiser to boot) into Carey's line-up of reactionary Modernists.

If what gets studied as Modernism has diversified, so too have the ways in which Modernism is analysed. Modernism was, of course, interdisciplinary long before the term became voguish, so it is not surprising to find exciting studies that work across the arts of Modernism.

Several important books have addressed the historical synergy between cinema and Modernism. The study of relevant periodicals has also flourished, exploring the numerous "little magazines" in which much Modernist art and literature was first published, bolstered by the work of the Modernist Journals Project in the US and the Modernist Magazines Project in the UK, which have pioneered digital editions of important magazines such as The New Age and Rhythm. The recently established journal Modernist Cultures also publishes much interdisciplinary work.

Outside the academy, museums and galleries are also revisiting Modernism. Modernism: Designing a New World 1914-1939, a 2006 exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, explored the impact of the movement on design and everyday life, from clothing to kitchens. In 2009, a major Tate Modern retrospective commemorated the centenary of Futurism, the first of many avant-garde isms that characterised the wider movement of Modernism. And a major exhibition on Vorticism, The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World, is currently running at Tate Britain until 4 September.

Modernist studies is a vibrant and exciting area of study, and many new postgraduates are being drawn to the field. The future is likely to mean more interdisciplinary work, increased attention to the transnational and post-colonial aspects of Modernism, and more discussion of the material culture of Modernism. Seeking to revive the radical energy and experimentation that drove earlier forms of Modernism is no bad thing in a contemporary cultural environment that often seems overly attached to the safe and the familiar. Debate will continue around the use of terms such as avant-garde, modern and Modernist to describe past as well as current works of art. And it is not inconceivable to imagine a time when the talk is once again of Post-Modernism, but the Modernism that it might supplant will this time be more accurately represented and considered. At the moment, however, the more likely picture is one in which diverse Modernisms continue to inform our cultural and artistic futures.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login