Christianity was not entirely overlooked in the Easter schedule. Bettany Hughes set out to discover if there was any point to forgiveness (What's the Point of Forgiveness?, BBC One, Friday 22 April, 9am). She spread a map on her car bonnet and wondered where to begin.

Christ's words on the cross seemed a good place to start. "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do." Didn't they? Such a plea, however generous, does not fit the story of Adam and Eve. They were punished because they had learned the difference between good and evil.

Forgiveness was foreign to the ancient world. You didn't love your enemies, you chopped them up. A panel in the British Museum, celebrating the victories of Assyrian King Sennacherib, provided a graphic instance of antiquity's preference for carnage over compassion. Jesus would change all that.

"Would he have recognised his ideals in the early Church?" asked Bettany. "That's an excellent question," said the Reverend Dr Grant Bayliss, by which he meant "No, he wouldn't." The history of Christianity is the distance the Church has travelled from the teachings of its founder.

Dr Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, talked about the difficulty of forgiveness. If it comes too easily, "it's as if the suffering doesn't really matter." It did for Cheryl McGuinness. Her husband Tom was the co-pilot of the first plane to be flown into the Twin Towers on 9/11.

Cheryl stood at Ground Zero where the work of reconstruction continues. She talked with great dignity about the men who had destroyed her life and crushed her children's hearts. She didn't want revenge. She rejected hatred. She made flesh the archbishop's words that forgiveness is a recreation, a reshaping of ourselves and those who have done us harm. A new beginning.

Just how hard it is to start again after a tragedy was one of the themes of Chris Chibnall's United (BBC Two, Sunday 24 April, 9pm). On 6 February 1958, a plane carrying a young Manchester United team failed to take off from a slush-covered runway in Munich. It crashed through a fence and a wing was ripped off as it struck a house. Twenty-three of the 44 people on board died, including eight members of the Busby Babes.

The action centred around Bobby Charlton, played by Jack O'Connell. He asked the big question: "Why wasn't I killed?" There was no answer. Time and chance happen to us all. Charlton's guilt was compounded by witnessing the goalkeeper, Harry Gregg, returning to pull survivors from the wreckage. "I couldn't have done that," he said. The one thing he could do for his teammates, play football, he nearly gave up. But he didn't. And every time he scored a goal, there was a roar in heaven.

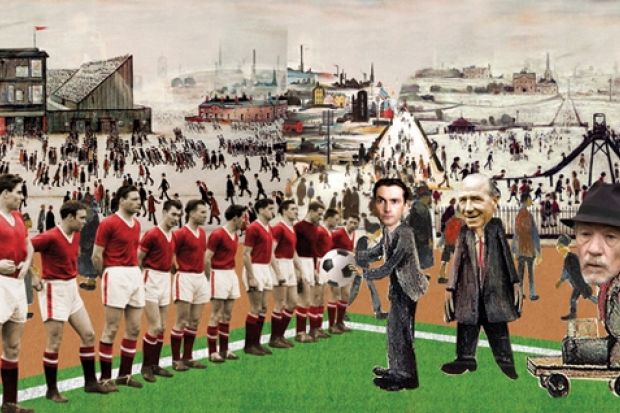

The photography, like the performances, was riveting. The period detail, from the Brylcreemed hair to boys reliving a cup final in a back alley, was precise. But there was poetry too. Several times the players were lined up in a tunnel, waiting to be called on to the pitch. "Cherish every kick, lads," said Jimmy Murphy, United's inspirational assistant manager, "it goes so quick." There was a clatter of boots as they ran out into the light, taking off at last.

A new documentary series, Perspectives (ITV One, Sunday 24 April, 10.15pm), kicked off with a portrait of L.S. Lowry. Sir Ian McKellen, who presented, wasn't quite able to suppress his thespian tendencies, at one point dressing like the painter and peering over a wall in a manner likely to get himself arrested. But his commentary was acute. Just as Beckett made us think about waiting, so Lowry makes us think about crowds. And there are no shadows in his paintings. This is true and not true.

A darker Lowry emerges with the works discovered after his death. They show a girl dressed variously as a puppet, a ballet dancer and a doll. The costumes were solid geometry, encasing her and emphasising her breasts and buttocks. If there is such a thing as Futurist pornography, this is it. The violence in the paintings is shocking. In one, the girl's head has been severed from her body. Where do these images come from? They seem so different from the stick figures swarming out of factories.

Perhaps these later works are a distillation of themes that can be found in the earlier ones. Certainly there is a strong sexual element in Lowry's painting. One shows a lighthouse rising out of the sea. But he could portray desire only in the abstract. Bodies are bent, misshapen, useless. And there is also violence. A Fight (1935) is an obvious example. Both come together in the sadism of these final pictures. Lowry is not the innocent, he is the primitive. After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login