Modern codex editions of classic works of literature generally come in two sorts. There is the variorum edition, which is directed towards academics and aims to establish an authoritative text, collating it with extant textual variants, including pre-publication materials such as manuscript drafts and proof copies. Then there are the "student" editions, which print a single text with a minimum of textual apparatus, and focus on providing contextualising materials to explicate the nuances of contemporary references that are assumed to be alien to the modern reader.

Unusually, Nicholas Frankel's new edition of Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray makes claims to both these territories, advertising the newness of its textual scholarship and its annotation. But can Harvard University Press' relatively expensive edition of Wilde's popular novel (£25.95) deliver on the promise that it is "annotated" and "uncensored", thereby justifying its position in an already overcrowded market? And what, for that matter, does it mean to be "uncensored"?

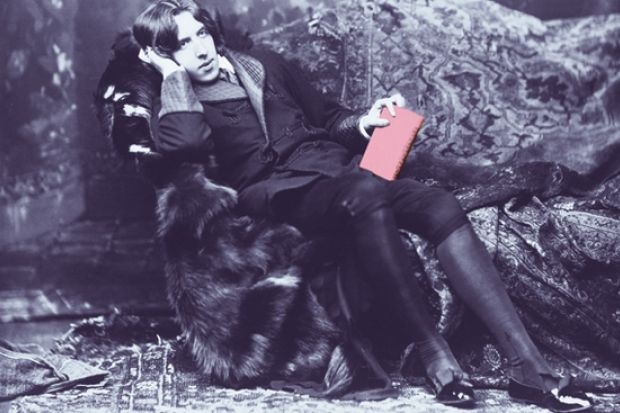

To begin with the annotation: like other volumes in this series, the Harvard Dorian Gray assigns contextual material a high priority, placing it in a column parallel to the main text. The principles that inform its selection are also distinctive. There are more than 60 colour illustrations, including photographs and drawings of individuals and objects (such as a Clodion statuette and a hansom cab) mentioned in, or loosely connected with, Wilde's novel, as well as reproductions of contemporary street scenes, illustrations from early 20th-century editions of the book and the publicity poster for the 1945 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film adaptation.

The narrative material gives us notes on "chocolate", "pianos" and "Samuel Morse" as well as more familiar literary topics, such as Charpentier's 1884 edition of Théophile Gautier's Emaux and Camees. With these choices, Frankel, associate professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University, sidesteps many of the vexed theoretical questions about annotation, such as who the average 19th-century reader might have been and how one reconstructs her horizon of expectations, in favour of encouraging a diverse range of engagements with Wilde's novel, not all of which are straightforwardly historicist.

His attitude towards textual issues is equally unorthodox. "Uncensored" is a loaded term, implying that the Dorian Gray with which we are familiar is inauthentic. Most current editions print the 1891 book version of Wilde's story; a few prefer the shorter text that appeared in the July 1890 edition of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine on the grounds that the revisions Wilde made to his story for book publication were unduly influenced by the hostile (some have argued homophobic) reception of the periodical version.

Suspicious of the authority of both these published texts, Frankel presents an even earlier Dorian Gray, one based on the typescript used to prepare the Lippincott text. As Frankel acknowledges, the typescript's existence has long been known to specialists; moreover, the differences between it and the Lippincott version are recorded in the textual apparatus in Joseph Bristow's 2005 Oxford University Press edition.

The originality of Frankel's volume thus lies not in the newness of its textual evidence, but in his treatment of the typescript.

Unlike all previous editors he uses it as the basis of his copy-text because it represents "a more scandalous and daring" Dorian Gray - a version of the story before it was "bowdlerised" by the Lippincott editor James Stoddart in an attempt to make Wilde's piece "acceptable" for a family magazine.

However, revealing that "scandalous and daring" Dorian Gray is not straightforward. The typescript is a complex document, marked up by several hands - including those of Wilde, Stoddart and an unknown third person. Frankel finds it important that Wilde had no further access to the typescript he had revised after it had been passed to his editor, and was therefore never consulted about later changes that found their way into the Lippincott text.

The aim of the Harvard edition is to preserve Wilde's emendations to the typescript while stripping away what Frankel terms the "purging" changes (the "vast majority" of which centre "on sexual matters") marked up by other hands. This "purged" material is recorded in a series of textual notes.

Frankel views some of the changes marked on the typescript as authoritative because they derived from Wilde, while others represent corruptions and are therefore to be disregarded. Proceeding in this way, Frankel aims to reconstruct that version of Dorian Gray which, in his view, Wilde would have published had he not been subjected to the censoring hand of an over-cautious periodical editor.

The conjectural nature of textual reconstructions of this kind - the creation of an "eclectic" text - means they will often be contentious, and Frankel's editorial practice, while undoubtedly giving us a new Dorian Gray, invites comment.

First there is the process of reconstruction and the problems (which to his credit Frankel acknowledges) of securely identifying the origins of all the changes marked on the typescript. It is particularly difficult to attribute to any one agent deletions indicated simply by words scored through, as well as alterations to punctuation. In the latter case, when Frankel cannot with certainty attribute changes to "Stoddart or his associates", he incorporates them into his text "as if they were Wilde's own".

Some editors will object; some readers might have preferred a facsimile of the typescript so they could judge these complexities for themselves.

A second question concerns the status of Frankel's text. Why should this Dorian Gray, a version of the story that no member of the 19th-century reading public ever had access to, lay claim to our attention? Is a "more scandalous and daring" work necessarily a better one, artistically speaking?

There is, after all, room for debate about the value of being explicit rather than being allusive; and there may be different views, too, about the significance which Frankel attributes to the spelling of "sphynxes" rather than "sphinxes", or "Sibyl" rather than "Sybil". At issue is not just the authority of local editorial interventions, but their meaning and value.

Few 19th-century authors had the freedom to publish exactly what they wished, and manuscript evidence from other parts of Wilde's oeuvre reveals that Stoddart was not the only editor to alter Wilde's prose. James Knowles, founder of the literary magazine The Nineteenth Century, cut lengthy passages from the essays "The decay of lying: a dialogue" (1889) and "The true function and value of criticism" (1890) without Wilde's full consent.

Although objecting to Knowles that it was "really painful...to have one's work touched", Wilde conceded that it was part of an editor's job to edit, to "consider space, to preserve a balance of contents" and that this inevitably involved exercising what Wilde termed "literary judgement".

Frankel might point out that the difference between the Knowles and Stoddart cases is that the former's deletions were guided by pragmatic and artistic concerns (needing to shorten Wilde's pieces, Knowles cut passages he found boring), while those of the latter were overtly political. Moreover, when his essays were later published in books, Wilde was able to restore excised material.

Against this, it could be claimed that for both editors commercial interests were uppermost; and in so far as he, too, wished to find a market for his writing, Wilde was not only in no position to object to such editing, but being "always in need of money" (as he confessed in 1890), he had no real interest in so doing.

The editorial principles guiding Frankel's edition rehabilitate a rather romanticised portrait of writerly integrity, that of the lone artist struggling against a philistine and coercive publishing industry. By contrast, book historians, viewing literature as an inherently social product, emphasise that the publication process in some sense makes all literary works collaborative endeavours. Distinctions between creative or censoring collaborations are often moot if not meaningless.

In this respect, the main value of Harvard's handsomely produced edition is that it enables the general reader to participate in this debate - although it remains to be seen whether they will be won over by the Dorian Gray with which they are presented.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login