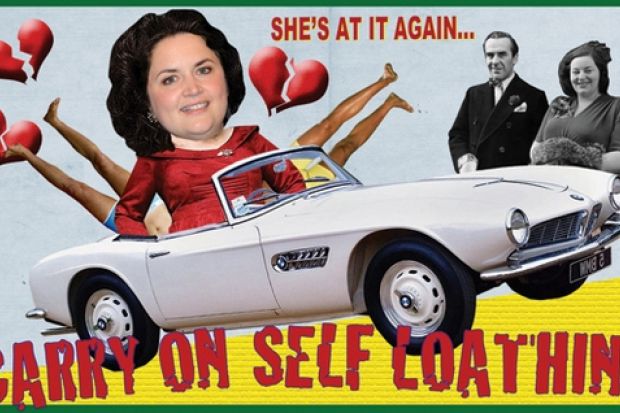

Hattie Jacques was the original Big Beautiful Woman. If the term had been around when she was alive, her self-loathing may have been a little less. There were glimpses of it in Stephen Russell's finely crafted drama Hattie (BBC Four, Wednesday 19 January, 9pm). "I need six months' notice to squeeze my behind in there," she said, referring to the back seat of a sports car.

It belonged to John Schofield, who had been sent to collect her from a charity function. Ten years younger than Hattie, Barbara Windsor described him as "stunning, a gorgeous bit of crumpet". She forgot to add that he was also a complete bastard.

"Why do you put yourself down?" he asked. "Anyone can see you are lovely." "I've got a nice face," Hattie retorted. Indeed she had. Bill Kerr, one of her co-stars in Hancock's Half Hour, compared her to Ava Gardner. But that is not what Hattie meant. People talked about her face so they wouldn't have to mention her figure. "I hate being the size I am with all my heart and soul," she once confessed.

Schofield, whose malignant charm was deftly captured by Aidan Turner, exploited Hattie's insecurities. "Are you chasing me?" she asked. "No, I am hunting you." Excitement blinded her to the menace of that remark. Could it be that she was attractive after all? Desirable even? Her husband, John Le Mesurier, had barely any sense of his own appetites, never mind those of his wife. You couldn't miss Hattie, but you could be in the same room as John and not notice that he was there. It takes great skill for an actor to play someone who is always on the verge of disappearing, but Robert Bathurst excelled at the task.

The first night Schofield took Hattie home, he followed her up the steps and pinned her to the front door with a kiss. The next time we saw him, he was in the garden playing with her children. Did he really want her? Who knows? It's hard to tell when a used-car dealer is being sincere. Either way, Hattie stooped to folly.

Vigorous sexual congress was conveyed by the rocking of a caravan on the set of Carry On Cabby. Hattie was turning out to be quite a hottie. As for Schofield, he was "unstoppable". "I can't give him up," she confided to a friend. He had the power to make her forget work, marriage and children. Ruth Jones movingly conveyed a woman whose heart was in one place but whose hormones were in another.

Hattie's dilemma was brilliantly anticipated in an early scene that saw her dangling from a broken winch as she rehearsed for a pantomime. Not quite on the ground nor quite in the air, she circled slowly in the spotlight in an empty theatre. She was playing the part of a fairy, Antedota, but there was no antidote for her fever. It may have been "a lovely way to burn" for Schofield and Hattie, but it was Le Mesurier who got torched.

Banished to the attic room, he was kept awake by a crashing symphony of sex. He and she had never made such music. There was one particularly poignant scene where the cuckolded husband tiptoed into his sons' bedroom to find one of them awake, scared by the noise mummy was making.

It was a cruel coincidence but also convenient that husband and lover were both called John, which, incidentally, was also the first name of Profumo, whose affair with Christine Keeler, the girlfriend of a Russian diplomat, was referenced in the film. Hattie had her attention drawn to the scandal by Esma Cannon, the actress who played a dotty little old lady in four Carry On films. Marcia Warren gave a wonderful cameo as Esma, shrewd enough to see where her friend's amour fou was headed. "Profumo's having an interesting life," she cackled. "Dirty bugger." She looked up from the paper and stared knowingly at Hattie. "You British never forgive people who like a lot of sex."

Le Mesurier forgave her though. He was prepared to be named as the adulterous party so that Hattie would have the public's sympathy instead of their opprobrium. What seemed like Le Mesurier's air of vague presence turned out to be a truly ethereal quality. Love indeed. He departed from the court with Joan Malin, whom Hattie had practically forced upon him as a way of alleviating her guilt. The look she gave them as they left suggested that she might have made a mistake. She had. Three years later Schofield dumped her. But not before giving her the odd black eye.

Schofield was the sullen working-class man, an urban Mellors for a showbiz Lady Chatterley. But Hattie wasn't really about angry young men, it was about how hating yourself damages those who love you.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login