The Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) has always had an image problem: observers (both supportive and critical) have paid a great deal of attention to the way members look, sometimes to the exclusion of their campaigns. Media coverage of the first WLM conference at Ruskin College, Oxford in February 1970 typecast participants through their dress: “a struggling crowd of long hair and maxi coats… the usual mud-coloured student crowd… communist girls in clothes out of Dr Zhivago” (The Spectator); “young, violent, radical, and very attractive with their long hair and maxi coats” (The Observer).

These stereotypes, or that of the braless, dungaree-clad, un-made-up feminist, constructed WLM members as a group apart from normal female experience. In 1971, one WLM group was contacted by an older woman who was sympathetic but “afraid she would embarrass us because she didn’t have any trousers” (Shrew, 3/3).

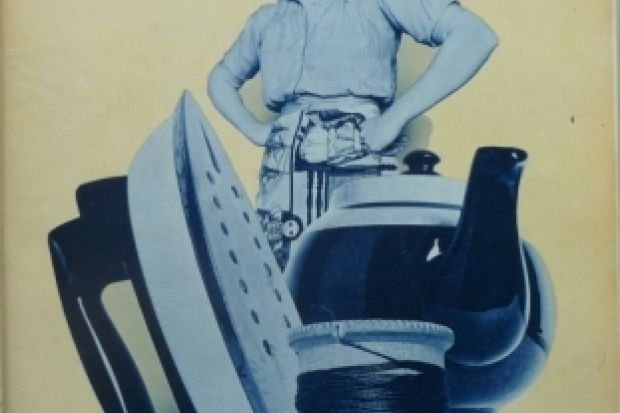

My research project on the politics of appearance explored how 1970s feminists actually presented themselves when image was so hotly contested. I investigated feminist magazines and newsletters such as Spare Rib, Shrew and Red Rag, and found they were full of discussions about fashion and women’s body images. Some were hostile to the fashion trade as a whole – “A treadmill described as a merry-go-round” (Shrew, 3/2) – but others examined fashion as a source of legitimate self-expression and pleasure. Spare Rib published patterns for DIY knitwear, clothes and furnishings, and thoughtful articles on the philosophy of fashion by the researcher and writer Elizabeth Wilson.

The feminists I interviewed revealed that in the 1970s they had experienced fashion as both oppression and self-expression. For some, involvement in women’s liberation was accompanied by a rejection of conventional fashion, such as the writer Michelene Wandor, who went from wearing miniskirts to a period when she had nothing but trousers in her wardrobe. Others tried different approaches: after a period when she was often mistaken for a man, Amanda Sebestyen, the freelance journalist and editor, started wearing flowery 1940s dresses – but with unfeminine shoes. Feminists involved in Gay Liberation enjoyed playing with gender stereotypes: Wilson passed on a Biba dress to a male friend, while Sue O’Sullivan, editor of Spare Rib from 1979 to 1984, used to go out “femmed-up” in a skirt, make-up and veiled hat.

The interviewees’ interest in dress and appearance, and their awareness of its power, has not been reflected in the historical record. Sebestyen has stated that the 1970s “were not a very visual time”, although surviving images of feminist events from the Miss World protest to Reclaim the Night marches show a keen sense of visual effect. There seems to have been some typecasting, perhaps drawing on iconic images such as the later Greenham Common protests. The historian Sally Alexander noted that a male companion from the 1970s remembered her wearing dungarees, although she never did. Cultural ambivalence towards dress may also be partly to blame, with fashion often characterised as not serious or political.

In fact, clothes can be both, as can be seen from the interviews, images and artefacts in the exhibition Ms Understood: Women’s Liberation in 1970s Britain, now at the Women’s Library, including jumpers and tapestries with Marxist and feminist logos made by Wandor for her friends. Jumpers and T-shirts with logos, and second-hand or ambivalent garments, had meaning not only through their appearance, but also through their distance from the conventional clothing required for many jobs.

It was shocking in 1971 to see a woman in culottes at the office; that it is not now is a result of feminists’ battles against discriminatory dress codes. Their insistence on being assessed on ability rather than appearance may sound dated, but the media’s obsession with looks, as was shown by the focus on Hillary Clinton’s wardrobe during the US elections, means it is still vital.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login