As Brian Ladd's introduction tells us, autophobia is "an obscure psychiatric diagnosis of 'fear of oneself'". Ladd justifies his use of the term to indicate fear or hatred of cars on the basis that cars are so ubiquitous that to hate them is "tantamount to fear of being human in the automobile age".

The opening chapter, on the attitudes of early motorists (including Mr Toad of The Wind in the Willows), considers their battle with ramblers for dominance of the countryside, citing examples from the UK, Germany and the US.

He goes on to examine the extension of automobility beyond the upper and middle classes and the impact of cars on the design and experience of our cities, a theme developed in the following chapter on "freeway revolts" and transport policies of the 1960s and 1970s. The concluding chapter reviews developments since the 1970s, most notably environmental objections.

No intended readership is specified for the book, and the omission implies aspirations to universality: perhaps Autophobia was conceived as the Fast Food Nation of car commentary? Certainly the writing is pitched at a general readership, with its loose, repetitive cadence, colloquial diction, scant use of references and lack of bibliography.

Autophobia contributes to scholarship an account, thematic as much as chronological, of "the triumph of the automobile through the eyes of those who hated or resisted it". But there are some drawbacks, in addition to the lack of apparatus noted above, that call into question the book's suitability for students.

First, while comparisons between automotive practice in the UK, the US and, for example, Germany are welcome, no rationale is provided for Autophobia's geographical coverage. So when Ladd tells us in his introduction that cars have killed 30 million people in the 20th century and 1.2 million each year since, we are left guessing whether this is a global figure, and what the method of data collection was, because no reference is provided.

And when all of the images used to illustrate the first chapter are from the British magazine Punch, even though the discussion extends across several nations, the reader is perplexed rather than reassured by Ladd's assertion that "this chapter, far more than the others, draws on a body of solid historical scholarship".

The existing literature on cars extends from urgent critiques such as Ralph Nader's Unsafe at any Speed: The Designed-in Dangers of the American Automobile, through considerations of the significance of the car in specifically American cultural history, such as James Flink's The Automobile Age, to anthropological accounts of the significance of the car within other cultures (for example, Car Cultures, edited by Daniel Miller) and feminist analyses that have revealed both the masculinist nature of car culture and the car's importance in assisting women with competing roles both inside and outside the family home (including Virginia Scharff's Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the Motor Age).

A recent anthology to which I contributed, Autopia, edited by Peter Wollen and Joe Kerr, has demonstrated something of this variety of approaches to understanding cars in the early 21st century.

Autophobia, then, is more usefully seen as a timely account rather than an original intervention. The science of climate change is becoming more prominent within popular culture and media channels and the ecological imperative to alter our daily lives accordingly has directly challenged our car usage, our mobility and our very freedom, in theory if not yet actually.

Ladd's account of the objections of automotive detractors clearly demonstrates that current concerns have precedents extending back continuously to the car's introduction. In this sense, he competently performs the role of the historian in helping us to understand the present through understanding the past.

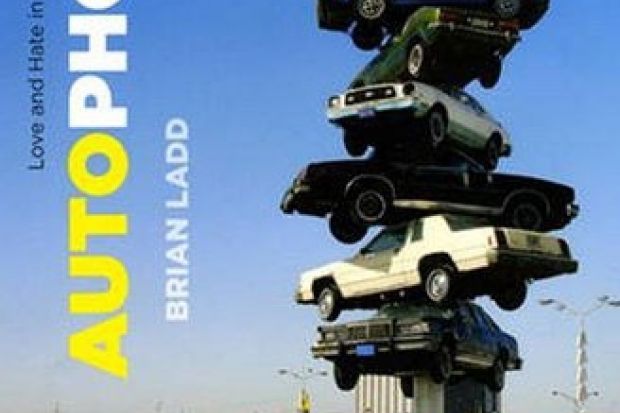

Autophobia: Love and Hate in the Automotive Age

By Brian Ladd. University of Chicago Press. 204pp, £11.50. ISBN 9780226467412. Published 1 November 2008

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login