There is a third person in my marriage. His name is Bob Dylan. My husband and I share love and commitment not only for each other but also for the sparkly spectrum of popular culture. Actually, the Pet Shop Boys got us together. But it was always Bob who created tension. This strange man of American culture seemed trapped in an endless 1970s of daggy fashion and shaggy hair. The harmonica wire framing his face looked like a dental brace that had slipped. His voice was out of tune. He stretched vowels into two time zones, and his political ambivalence and changeability were a tepid leftover from a kinder, gentler time.

While I banned Bob from the lounge stereo, every so often I would catch sonic bleeding from my husband's headphones. He was listening to Like a Rolling Stone. Again. I arrived home from work. As I put the key in the lock, I would hear "Don't think twice, it's all right" being ripped off the CD player or forwarded on the iPod. Again. I didn't mention it. Bob always seemed to be with us.

In the past couple of years - and this demonstrates how far my acceptance of WMMB (Weird Masculine Musical Behaviour) has moved since those early days of marriage - I now realise it is me, not Bob or the headphoned husband, who has the problem. Ironically, it was a film that taught me to revalue and reinterpret Bob, his music and his era. With I'm Not There - unjustly - missing out on Oscars this year, it is important to remember the earlier film that started Dylan's revival (again).

It was only a matter of time before the legendary director Martin Scorsese returned to documentaries and Dylan. His Last Waltz, featuring the final concert of The Band, had Bob as a bit-player in a masterful review of American roots music. His The Blues television series shifted our sonic landscape and reshaped and reclaimed archival footage of the early bluesmen. No Direction Home completes the journey. It is a three-hour, 29-minute documentary that is gripping, horrifying and very funny. Original interviews are featured, including Dylan's review of his own life as told to manager Jeff Rosen. Joan Baez is her usual cool and brilliant self. Forty years later, she is still angry at Bob for - either - leaving her or not sharing her politics. Passion and principles were entangled and confused. Remember it was the 1960s, man.

Scorsese and Dylan never met to make this documentary. Seemingly, they share enough history to make a conversation irrelevant. They understand New York. They understand the 1960s. They understand the blues. They share a cultural language. That dialogue has created great film-making. Both are outsiders - abrasive and difficult - who discover alternative paths though the most conventional subjects.

It is the found footage of an impossibly young - and actually handsome - Dylan from 1962 until 1966 that is the gift of the documentary. I'm Not There builds on the cultural knowledge and imagery assembled and edited by Scorsese. Surrounded by old, rude and profoundly ignorant journalists, Bob handled so much stupidity by the age of 25 that he even foreshadowed his own Buddy Holly-like exit strategy. The most cringing moment of the documentary is when an incompetent and - frankly embarrassing - British photographer asked Bob to "just suck on your glasses" for a picture. I am glad to report that Dylan did not comply. Instead, he tried to force the arm of his glasses into the photographer's mouth.

These press conferences feature dreadful journalists asking dumb questions. While we are accustomed to such patter through the endless stream of talk shows and celebrity interviews, No Direction Home is different because Dylan answers back. If he thinks the question is ridiculous, he gives a ridiculous answer. He asks for precise definitions of journalistic terms and concepts, which they cannot provide. My favourite rejoinder is his angry voice howling "you've got a lot of nerve asking me that".

When watching Dylan handle a press conference, we see the consequences of celebrity culture on the standard of debate and argument in our bland, blind age. I will give any reader of Times Higher Education £1,000 if they are interviewed on Richard and Judy and howl "you've got a lot of nerve asking me that" to Madeley after he asks xenophobic questions about "foreigners", Japanese game shows or how British soldiers are "giving democracy" to the citizens of Iraq and Afghanistan. Any statement from the Daily Mail - quoted as fact rather than diatribe - can be greeted with the same response. Dylan would be proud.

In describing his first great musical model and mentor Woody Guthrie, Dylan realised that, "you could listen to his songs and actually learn how to live". Bob holds a similar role. He is defiant, uncomfortable and avoids all categorisation. He changes his mind and views at a whim, seemingly to stop the precise pigeonholing of his music, life or views.

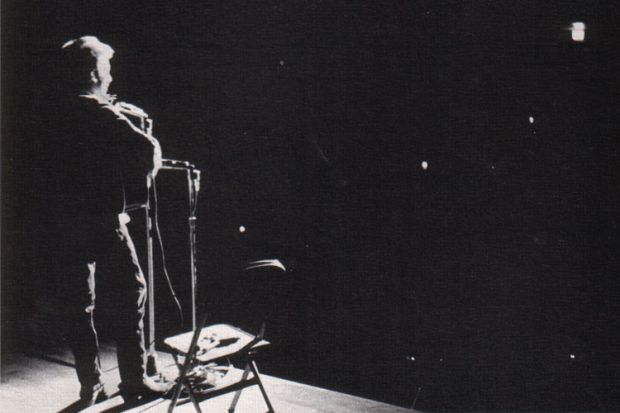

Popular culture - when fresh - is riveting and revelatory. Dylan remains an outsider who became part of popular culture and then changed popular culture. Recognising this influence, Scorsese did something clever and important when telling his story. He stopped the documentary at 1966 with the footage of the famous concert in Manchester's Free Trade Hall where a distraught folkie - semiotically electrocuted by a plugged-in Dylan - yelled "Judas". The witty reply - "I don't believe you. You're a liar" - was fully audible to the audience. He then turned to the band and spat a forthright and punchy instruction about the volume of the next song. A heart-starting snare drum erupted from the stage, commencing Like a Rolling Stone. So ends the Scorsese documentary.

We demand too much of our popular cultural icons. We want Britney Spears to remain that young virgin with an edge of knowingness in Baby One More Time. We want Amy Winehouse to be slightly druggy and disoriented, but not fully druggy with a crack pipe. We want Madonna to stay as our youthful icon getting into the groove, without the cadaver-like facade of Dorian Gray in a frock. But really, it is our expectations that are out of order.

If a writer, designer, musician or film-maker produces one sentence, motif, song or image that changes our world, then that is enough. To expect these great minds and talents to continue to produce innovation after innovation, revelation after revelation, is unrealistic. It also means that we mortgage our past and present for a cultural future that will never happen.

Bob taught me that. He also taught me that where we start is not our destiny. At his most poetic and ambiguous he confirms that, "I was born very far from where I was supposed to be born, so I'm on my way home". So are we all. To paraphrase two other volatile critics who also changed culture, we make our own history, but not of our choosing. The choice comes in selecting the soundtrack for the journey. And - in the end - Bob is a good guide: he knows the direction home.

Tara Brabazon is professor of media studies at the University of Brighton.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login