Source: Scott Grummett

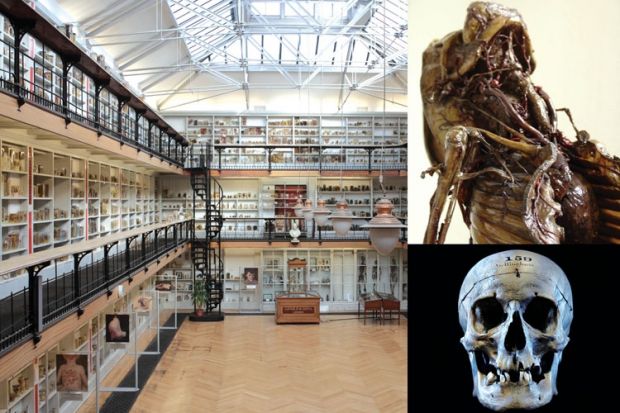

Pathologically minded: the ‘Shellac child’ (top right) and the skull of assassin John Bellingham (bottom right): just two of 5,000 specimens held by the museum

One of the UK’s most unusual museums is hosting a series of public lectures exploring everything from the country’s first female serial killer, Victorian cemeteries and the history of gin to the bacteria responsible for bad breath.

Now part of Queen Mary, University of London, the Barts Pathology Museum was opened by the Prince of Wales in 1879 and offered essential training to generations of medical students (it started with a collection of bladder stones and slowly built up from there).

The museum is located in a striking Grade II-listed open plan space on three mezzanine levels. Among its 5,000 specimens are: the skull of John Bellingham, the only successful assassin of a British prime minister (Spencer Perceval in 1812); a tight-lacer’s liver, revealing the deformities caused by a lifetime of wearing corsets; a tubercular rat; and a cabinet of objects found in people’s orifices.

The museum gradually lost its rationale with the increasing prevalence of drug-based treatments and the use of virtual reality in teaching. Both its infrastructure and pathology pots were deteriorating rapidly when funding was secured two years ago to renovate a fascinating collection that otherwise would have disappeared without trace.

Carla Valentine, a qualified anatomical pathology technician who used to work in a mortuary, was appointed assistant technical curator and tasked with repairing, conserving and cataloguing all 5,000 specimens and rearranging them “in a way that keeps the Human Tissue Authority happy, as well as students and allied health professionals”.

Once this process is complete, it may be possible to offer daily access to the museum.

In the meantime, Ms Valentine began to see the potential of the venue as a place to hold lectures on slightly macabre themes, usually with some sort of link to the collection itself. Although she claims that “no one finds it spooky or ghoulish, visitors’ journeys of wonderment begin when they walk into this vast unexpected space. It’s like falling down a rabbit hole, which makes a very good start to a lecture.”

There is also room for a bar, sometimes with suitably themed drinks: for example, Black Dahlia cocktails were served at a talk on the notorious Black Dahlia murder case in 1940s Los Angeles.

A new series of Wednesday lectures begins on 25 September with Sarah Tobias looking at “Death and Mourning in Victorian England”. On 23 October, Ms Valentine will open up the second floor of the museum for the first time and describe her experience of “refleshing the bones” – reconstructing the lives of people whose body parts are now specimens.

Take the case of Leonard Mark, for example. “He was one of the museum’s illustrators,” explains Ms Valentine, “but suffered from acromegaly [a malfunction of the pituitary gland that can lead to disfigurement], so parts of his body are on display. He spent so much of his life working here and ended up in the pots for evermore.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login