Source: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

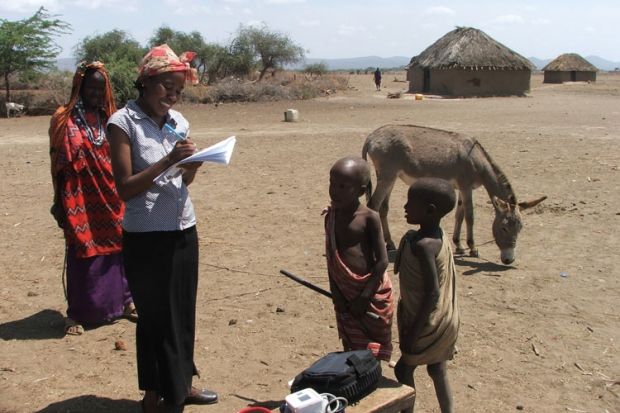

On the ground: gathering data in the field is essential to a firm statistical basis for research

The gilded snake, rat, mosquito and bedbug displayed on the balconies around the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s elegant art deco building in Bloomsbury may make a striking architectural feature, but they also give a rather one-sided picture of what the school is about today.

There is still a Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, which has many joint clinical appointments with the nearby Hospital for Tropical Diseases. Mosquito larvae are kept in the basement and fed on Heinz breakfast food. Brave volunteers come and offer their arms so that the mosquitoes can drink blood, as they prefer, direct from bodies. Yet the two other faculties, of Epidemiology and Population Health, and Public Health and Policy, focus much of their efforts on the UK and Europe, rather than the tropics. Major areas covered, says vice-director (and professor of health economics and policy) Anne Mills, include “cancer epidemiology”, “obesity and exercise”, “sexual health”, drug abuse, gender violence and the specific health issues of “hard-to-reach populations”.

Professor Mills started her career as a health economist at the Ministry of Health in Malawi in 1973 but moved to the LSHTM six years later. She still devotes a day a week to research, currently including a project on expanding coverage in health services in South Africa and Tanzania. She recently organised a conference called Health Economics: Coming of Age to celebrate the school’s “central role in the development of the discipline” and to reflect on the challenges that lie ahead.

“Health economics has been growing rapidly since the 1970s,” she says, “after it was recognised that health is a very significant sector in the economy, and so something natural for economists to study. We have the largest group of health economists in the world – around 30-40 academic staff – working on issues of health in lower- and middle-income countries [LMICs]. They look at how best to finance health services; the relative performance of public and private providers; how you expand access to health services; and different financing sources such as user fees, insurance and general taxation.”

Although they do little direct consultancy for governments, Professor Mills believes that their research is a crucial resource for LMICs, where there is often “enormous scope to implement interventions that are very cost-effective”.

A number of factors contribute to the LSHTM’s success in these areas. One, in Professor Mills’ view, is “well-consolidated partnerships in those countries and over 100 staff based overseas on a long-term basis, embedded in local universities, research institutions and public health foundations”.

Equally important is a deep commitment to multidisciplinary research. This often enables the school to bring together a core team of a health economist, an anthropologist or sociologist, a clinician, an epidemiologist and a statistician who can examine the acceptability as well as the cost-effectiveness of healthcare interventions.

Health economists working in LMICs also face a number of specific challenges. One is often a lack of good information systems and government statistics, so research has to include much basic data-gathering out in the field. Professor Mills also notes that “much funding comes from those interested in direct policy implications, so it has been much harder to do the more methodological and theoretical research. In the UK, it has been easier to build health economics as a discipline, but you can’t easily transfer the lessons, because of the structure of the economy, the extent of poverty, the level of government capacity and so on.”

The past decade has been a good time for medical research, with increasing funds coming into the school from the research councils, the European Union, the Gates Foundation, ring-fenced NHS and international development budgets and other sources. Since the LSHTM is a postgraduate, highly research-intensive institution, where teaching activity accounts for only about 15 per cent of academics’ time, Professor Mills is acutely aware of the need to “retain research income in what will at some point become a more adverse environment” and cautiously supports the idea that they should be “more active in consultancy work, commissioned research, some of the more commercial activities such as an insecticide-testing service”.

But for the moment, the financial base remains solid and the school continues to maintain its place at the centre of debates about health economics and public health more widely.

In numbers

15% - Amount of academics’ time spent teaching at the LSHTM

matthew.reisz@tsleducation.com

Campus news

Newcastle University

The first doctors trained at a UK university’s overseas campus are set to graduate this week. A cohort of 20 medical students at Newcastle University’s medical school in Johor, Malaysia, will take part in a graduation ceremony on 28 June. In 2011, the institution became what it claimed was the first UK university to establish a medical campus overseas – Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia (NUMed). The graduates will be eligible for provisional registration with the UK’s General Medical Council and the Malaysian Medical Council.

University of Sheffield

Taxation in the UK has become increasingly regressive since the financial crisis, a report reveals. The Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute, based at the University of Sheffield, found that the contribution to total revenue of progressive taxes such as income and capital gains tax fell from 58 per cent in 2007-08 to 54 per cent in 2012-13. The contribution of regressive taxes such as VAT rose from 25 to 28 per cent of the total over the same period.

University of Oxford

Academics and school teachers from Papua New Guinea spent two weeks at a UK university as part of a project to improve teaching in the country. The intensive course, run by the University of Oxford’s department of education, focused on maths, science and English literacy. The group visited local schools and discussed the issues facing teachers in Papua New Guinea during the course.

Plymouth University

All eyes may be on the Brazilian cities hosting Fifa World Cup matches this summer, but a footballing contest of a very different kind is taking place in another part of the country. Students from Plymouth University are taking a five-strong team of footballing robots to the city of João Pessoa for RoboCup 2014, which begins on 21 July. The team will battle it out against others from the US, Japan, China and Europe.

University of Leicester

Academics hope a website hosting a vast range of resources on the writer Evelyn Waugh will encourage the public to contribute to a project to publish his complete works. The researchers, from the University of Leicester’s School of English, would like members of the public to send them any lost pieces of writing of Waugh’s they are aware of, to help identify the writers of letters sent to him, and to put them in touch with people he refers to in his writing.

University of East Anglia

Would you consider bringing your dog into university so that it could interact with students on campus? The University of East Anglia has piloted a Pets as Therapy (PAT) Club, inviting students – particularly those with a disability, or chronic or mental health problems – to interact with animals, with the aim of enhancing their general well-being. More than 300 people attended the PAT session, which featured seven dogs, and the university is hoping that staff members will consider bringing their own pets to campus to do similar work.

King’s College London

Drilling to remove tooth decay could be consigned to history as the result of a technique devised by university researchers. In a painless process created by a spin-off company at King’s College London, minerals are “pushed” inside a damaged tooth using a small electrical current, which allows it to heal by itself. Reminova, based in Perth, Scotland, believes it could create an alternative to the dental fillings received by some 2.3 billion people worldwide each year.

Birkbeck, University of London

A 71-year-old grandmother now studying visual arts has been honoured for her commitment to lifelong learning. Radha Virahsawmy, a former housing benefit officer, is in her second year at Birkbeck, University of London, which runs courses near her home in Leyton, East London. Ms Virahsawmy, who moved from Mauritius to the UK in 1967, was awarded a regional award for Adult Learners’ Week, which ran from 14 to 20 June.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login