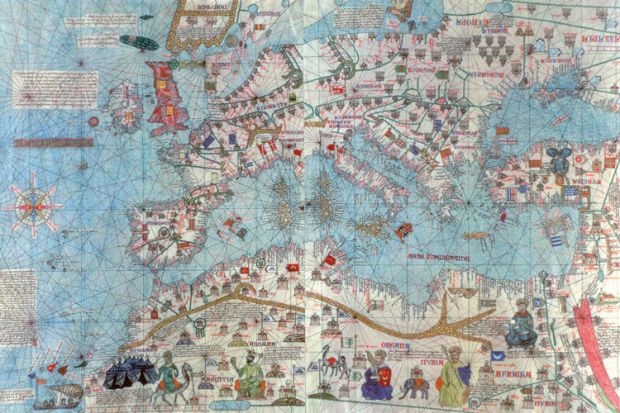

Source: Getty/Alamy

‘The notion of leisure travel is completely alien to the medieval world. People didn’t go to other places for vacations.’ Travel was always hazardous, physically and mentally

What can the travels of pilgrims, soldiers and merchants in the Middle Ages teach students about the conflict-ridden and interconnected world in which they live today?

Plenty, according to historians such as Michele Clouse and Jeffrey Bowman. They are among a growing number of medieval and early modern historians who make extensive use of travellers’ tales in their undergraduate courses - not only to engage students, but also to make them think about how cultures and belief systems collide.

For Clouse, who teaches at Ohio University, a large public institution, the tales complement the political and military chronology of her world history survey course, a breakneck semester-long dash from early humankind to the mid-18th century. “That’s five continents and roughly 5,000 years of history in 15 weeks,” she says, a little wearily.

“I want students to come away with a sense of how modern events are embedded in history,” she adds. “The parts of the world I’m talking about include China, India, most of Africa and the Middle East - regions that are in the headlines every day. The students need to think about how people whose beliefs and practices were very different from their own encountered other cultures.”

Travellers’ tales are ideal, says Clouse, because they are personal stories and are “not bogged down with the interpretations of historians”. Students can empathise with the traveller. “From their own experiences, they know that travel is challenging. You come to a foreign country: you don’t know the laws, you don’t know the rules, you may offend people, you have to deal with issues of cultural diversity. Students become more aware of their own biases by seeing the biases of others.”

All medieval travellers had a bias - or at least a travel agenda - according to Bowman, who teaches a first-year course, Crusaders, Pilgrims, Merchants and Conquistadors: Medieval Travelers and Their Tales, at Kenyon College, a private, liberal arts institution in Ohio. Whether the goal was conquest, trade or spiritual growth, the journey shaped the narrative.

Of course, unlike today, “the notion of leisure travel is completely alien to the medieval world”, says Bowman. “People didn’t go to other places for vacations.” Travel was always hazardous, physically and mentally. Ships sank in winter storms in the Mediterranean. Bandits robbed pilgrims and merchants. Travellers were away from their homes and families for months or years on end.

According to Bowman, the medieval and modern worlds of travel come closest together on the business trip. Like modern business travellers, who spend most of their time in airports, hotels and meeting rooms, merchants’ observations were limited by what they saw.

Mediterranean cities with major trading networks maintained the medieval equivalent of business hotel chains. In Istanbul or Alexandria, the merchant stayed and set up shop at the funduq (Arabic) or fondaco (Italian), a combination hotel and warehouse. “It was rather like staying at the Airport Marriott,” says Bowman. “At the funduq, the merchant would, for better or worse, be somewhat insulated from the temptations of the city.”

Merchants’ letters focused mostly on routine business matters - from the costs of shipping and commodity prices to battles with grasping toll collectors. “They judged the success of a trip by whether they made it home and made a profit,” Bowman explains. “They were on the road to make a living - not to write a travel guide.”

The accounts of religious pilgrims, Christian and Muslim, are richer with descriptions of places, peoples and cultures. Most recounted their physical and spiritual journeys, with some advice on planning and routes. The top three destinations for Christian pilgrims were Jerusalem, Rome and Santiago de Compostela in Northwest Spain, where the apostle St James is said to be buried. For French pilgrims, a 12th-century guide to Santiago was the medieval equivalent of today’s Rough Guides and featured descriptions of roads, river crossings and shrines to visit, along with caustic comments on the ethnic groups living along the route (see page 4).

In 1325, Ibn Battuta, a Muslim cleric and legal scholar, set out from Tangier (on the north coast of present-day Morocco) for the hajj to Mecca. He ended up travelling for most of his life. He traversed the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Persia, spent 12 years in the Indian subcontinent and travelled to Southeast Asia and China before returning to North Africa. In 1351, he was back on the road, across the Sahara to Mali. Finally, he sat down in Fez with another Muslim scholar to record 30 years of travel experiences.

“He wound up travelling around 75,000 miles, most of it by camel,” says Clouse. “The whole idea of riding around on a camel for 30 years is amazing to the students because the only camel most have seen is on the internet. They haven’t even seen camels in a zoo.”

As a Muslim, Ibn Battuta was required to undertake the hajj only once in his life. “He sets out for Mecca, but he doesn’t go straight there and he doesn’t come straight home,” says Bowman. “He’s nominally a pilgrim, but there are other motives for his travel. Maybe curiosity, maybe anthropology, maybe market research. He spends a lot of time talking about markets.”

“He’s a religious man,” says Clouse, “but religion is just one component. It doesn’t define him as a person. Students connect with him because he’s human. He gets robbed a couple of times and faces other dangers. He has dalliances with different wives. We see that the people of his time were driven by the same desires and passions as today - sex, money, power.”

Ibn Battuta has often been compared to the most famous medieval Christian traveller, Marco Polo. Both, says Bowman, were “eagle-eyed observers of the world around them” but also “make opinionated remarks about their co- religionists who don’t practise Christianity or Islam in the way they think it should be practised”.

Ibn Battuta encountered Islam from North Africa to Southeast Asia, and critically noted variations in beliefs, practice and the administration of sharia. His observations raise the classic question about applying today’s moral standards to the past. Class discussions on the punishments of sharia and women’s lives are often heated. “How do we understand a society that accepts polygamy without judging it against our own?” asks Clouse.

She uses Crusader travel narratives to show common ground between religions.

“In one encounter, a Muslim traveller and two Christian monks are discussing their faiths. Students are amazed to learn that the faiths are part of the same tradition and their tenets are similar. That’s not an impression of Islam they get from today’s media.”

Conquistador narratives such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo’s The Conquest of New Spain, documenting Hernando Cortés’ campaign in Central America and the collapse of Montezuma II’s Aztec Empire, raise similar questions of cultural encounter and conflict.

“The Spanish know they’re in a different place and these people aren’t Europeans, but they spend a lot of time talking about difference, trying to piece together a belief system,” says Bowman. “They start asking questions.”

Some pragmatic queries, says Bowman, came from a European perspective: “If these people don’t have a concept of property, then is it OK to take all their stuff?” Other questions are more complex or ethnographic. The conquistadors never clearly articulated their mission: were they on a military expedition, a crusade or some combination of the two? That led to questions about how to treat the population, according to Bowman: “They are heathens, and that’s bad. But does this mean we should kill them? Should we enslave them? Or should we convert them?”

The whole idea of Ibn Battuta riding around on a camel for 30 years is amazing to the students because the only camel most have seen is on the internet. They haven’t even seen camels in a zoo

Travel narratives can challenge other cultural stereotypes. The accounts of Christian monks who travelled to the court of the Great Khan at Karakorum in the 13th century counter popular views of the Mongols as a murderous horde, pillaging their way across Asia and Europe. Bowman’s students read a positive account, by William of Rubruck, of the Mongol capital’s markets, temples and cosmopolitan population.

It is easier for students to accept the Flemish Franciscan’s admiration of Mongol culture than some of his other observations. His narrative includes descriptions of fantastic races of people “with faces in the middle of their bellies”, says Bowman. “We know this can’t be true, both historically and biologically, so it raises interesting questions about the reliability of the witness.”

Fantastic and mythical peoples and creatures have figured in travel narratives since before the times of the Greeks. And of the 400 or so pages of the Roman Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, says Clouse, “398 are in the compass of what we would call the fantastic - boys riding on the backs of dolphins, and the land of monstrous races”.

Accepting the fantastic as part of history seems an intellectual stretch for Clouse, a historian of science and medicine, but she rises to the challenge. “We have to suspend our judgement because the Greeks and Romans in their explanation and understanding of the world truly believed these places existed,” she says. “I tell students: ‘I’m not asking you to believe something, but you have to accept that they did.’ That’s a hard mental leap, but those who make it are well on their way to getting something really important out of history.”

For medieval, social and cultural history, personal stories - travellers’ tales, diaries, journals and letters - are “the best way to get students interested in contacts between cultures”, says Clouse. Other primary sources such as legal codes, royal decrees and religious texts may be more significant, but they lack narrative and characters.

In an upper-level class on the Renaissance, Clouse’s favourite villain is Benvenuto Cellini. “He’s the greatest goldsmith of his day, he works for the Pope and the King of France, and he travels across the Mediterranean and Western Europe. He was also considered a thief, spent time in prison, beat women and may have raped young boys. Students love to hate him but they can’t stop reading him. He epitomises everything that was amazing about the Renaissance and everything that was dark.”

How well a traveller represents a place or a time is a question Bowman poses to students. In the Crusades, “a single narrator has to stand in for hundreds of thousands of crusaders. You have to ask yourself whether or not the single witness is doing a fair job of conveying the motivations of the other crusaders. We can’t assume the most articulate witness speaks for everyone. Most were illiterate, so inevitably a literate person composing a narrative is not representative.”

The problem in dismissing travellers’ versions of events as unreliable or biased is that other accounts do not exist. “If you decide there’s nothing to learn from this witness, you’re out of luck because you can’t just call up another voice from the period,” says Bowman. “Travel narratives dramatise many of the interpretive challenges of historical evidence. They prompt students to think about questions of authorship, audience and reliability. In any text, you have to understand the personality and motivations of the narrator and ask if there are any other sources to use as a test. The answers to those questions are going to be different for every text.”

Clouse says students should not rely on travel narratives for accurate accounts of persons or events, but use them as windows on culture and the perceptions of the traveller: “Because Ibn Battuta travelled for so long, you get to see how his perspectives changed over time. What were the catalysts for change? What did he see that strengthened his own beliefs and practices?”

Travellers’ tales also challenge the stereotype of the Dark Ages, when people lived in ignorance of other peoples and cultures.

“Students think that globalisation only happened about 50 years ago,” says Clouse. “Ibn Battuta is one of the most travelled persons in history. He encountered so many people in so many places. You get a sense that people were moving around in ways that we really haven’t understood before. I want students to understand how much interconnectedness there was in the medieval world, how much contact between peoples.”

Pilgrims’ progress: Rough guides to harsh places

Excerpts from The Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago de Compostela, a 12th-century manuscript

“At a place called Lorca, in the eastern part [of Spain], runs a river called the Salty Brook. Be careful not to let it touch your lips or allow your horse to drink there, for this river is deadly! On its bank, we met two men of Navarre sitting sharpening their knives; they are in the habit of skinning the mounts of pilgrims who drink that water and die…All the rivers between Estella and Logroño have water that is dangerous for men and beasts to drink, and the fish from them are poisonous to eat…All the fish, beef and pork of the whole of Spain and Galicia cause illnesses to foreigners.”

“If, by chance, you cross the Landes region [of southwest France] in summer, take care to guard your face from the enormous insects, commonly called guespe [wasps] or tavones [horseflies], which are most abundant there; and if you do not watch where you put your feet, you will slip rapidly up to your knees in the quicksand.”

“In this [Basque] country there are evil toll-keepers, that is, near the Port de Cize, at the town which is called Ostabat, and at the town of St- Jean and St-Michel-Pied-de-Port - may they be utterly damned! For they go and stand in the way of the pilgrims with two or three big sticks, extorting an unjust toll by force. And if someone passing through does not want to give them money in accordance with their demand, they both beat him with the sticks and snatch away the assessed sum from him, upbraiding him and searching him down to his underwear. These are ferocious people, and the land in which they dwell is considered harsh…the ferocity of their faces and their barbaric speech arouse great fear in the hearts of those who see them.”

“The Gascons talk much trivia, are verbose, mocking, libidinous, drunkards, prodigious eaters, badly dressed in rags and bereft of wealth; however, they are given to combat and are remarkable for their hospitality to the poor.”

“[The Navarrese] are commonly said to be descended from the race of the Scots because they are similar to them in customs and appearance…This is a barbarous race, full of malice, swarthy in colour, evil of face…empty of faith and corrupt, libidinous, drunken, experienced in all violence, ferocious and wild, dishonest and reprobate, impious and harsh, cruel and contentious, unversed in anything good, well-trained in all vices and iniquities, in everything inimical to our French people. For a mere nummus [a low-value copper coin], a Navarrese will kill, if he can, a Frenchman…However, they are considered good on the battlefield, bad at assaulting fortresses…[and] accustomed to making offerings for altars.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login