Source: PA

From early on, Hütter had declared that rather than just play songs, Kraftwerk’s ambition was to perform Musikgemälde (musical paintings)

In November 1974, one of the most ground-breaking albums in contemporary music was released: Kraftwerk’s Autobahn.

The Düsseldorf quartet changed the course of popular music by discarding drums and guitars, along with all the other attributes of Anglo-American rock’n’roll. Clad in sober suits, they stood motionless onstage while they operated their electronic machinery. Their lyrics were mostly in German and delivered with the robotic voice of a vocoder. Some dismissed Kraftwerk as a Teutonic novelty act. Others realised that their machine music, in a literal sense, represented the sound of the future. Many of the band’s central concerns can now be seen as startlingly prophetic.

Kraftwerk’s electronic sound was so ahead of its time that the band did not even have a name for it; “techno pop” was one suggestion, “robot pop” another. Ralf Hütter, the artistic force behind the band alongside Florian Schneider, liked to describe their style as elektronische Volksmusik (electronic people’s music), ie, an electrified type of German folk music fit for the late 20th and 21st centuries. Given the country’s Nazi past, young Germans such as Hütter and Schneider sought a cultural identity that was not tainted by Fascism or American pop culture and looked towards a brighter future – one that would inevitably be dominated by technology.

Skip forward 40 years from Autobahn to today and Kraftwerk’s future music has proved to be revolutionary: “Synthetic electronic sounds/Industrial rhythms all around”, as they put it in Musique Non-Stop (1986), and that is indeed the case. Chart music from hip hop and R&B to manufactured pop is being produced on computers. Techno and house music have spawned a vibrant club culture, ranging from commercial super-clubs to experimental sub-genres. Just as Kraftwerk first claimed and demonstrated, the development of popular music is inseparably linked to technology. And even more so today, as both the production and the distribution of music have gone digital.

With a remarkable run of four pioneering concept albums from 1975 to 1981, Kraftwerk provided the blueprint for electronic music. But Hütter and Schneider, who liked to present themselves as robots, were only human after all. From the early 1980s, the rest of the musical world on both sides of the Atlantic caught up with the pioneers from North Rhine-Westphalia and their musical creativity stalled. Their secluded Kling Klang studio in the Düsseldorf red-light district needed a digital upgrade. And so did their back catalogue: Kraftwerk’s sound engineer Fritz Hilpert spent years faithfully transferring analogue tapes to digital equipment while Hütter and Schneider were cycling along the Rhine valleys. Meanwhile, Karl Bartos and Wolfgang Flür left the band, frustrated about the creative dead end. The musical man-machine had broken down. Kraftwerk, to all intents and purposes, seemed finished by the late 1980s.

Yet, although it lasted some 15 years, this technical glitch proved to be temporary. Kraftwerk’s artistic hibernation ended in 2003 when Tour de France Soundtracks was released, their first album of original material since 1986. In Germany, it shot straight to number one. A promotional world tour resulted in the live double-album Minimum-Maximum (2005), while the centrepiece of Kraftwerk’s astonishing comeback came in 2009: a lavish box set containing all eight albums from Autobahn to Tour de France Soundtracks titled Der Katalog (The Catalogue).

This groundbreaking body of music was presented in improved sound quality thanks to careful digital remastering, while the cover artwork received a minimalist design makeover. Der Katalog served as a reminder of Kraftwerk’s immense musical achievements, and it was widely acknowledged as such. However, it also coincided with another crucial event in the history of the band as Schneider quit his partnership with Hütter – acrimoniously, by all accounts – soon after its release. Once again, Kraftwerk seemed finished.

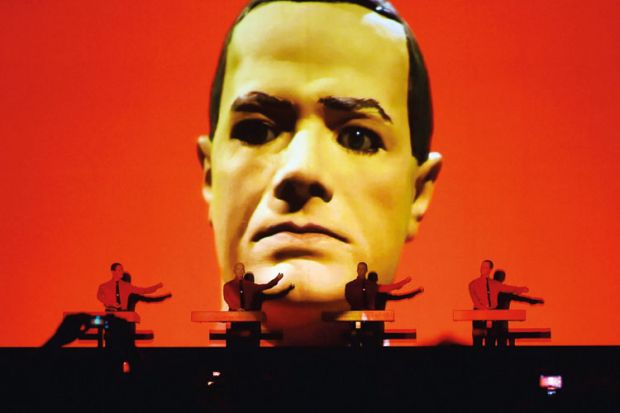

Despite looking like an epilogue, however, Der Katalog heralded a decisive phase in the artistic evolution of the band. Under the sole leadership of Hütter, it now focused on the visual side with the aim of transforming the band into what Richard Wagner called a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), fusing music, performance and visuals. From early on, Hütter had declared that rather than just play songs, their ambition was to perform Musikgemälde (musical paintings) through the marriage of music and projections onstage.

Working with his long-time collaborator, the artist Emil Schult, he revised and enhanced these video projections. This update stressed the retro-futurist concept that had characterised the band’s identity from the beginning: a hybrid of nostalgic and ultra-modern imagery that created a disjointed sense of time. In recognition of the manifold influences of modern and contemporary art, the new visuals were exhibited for the first time in 2011 as stand-alone works of art in galleries.

Appropriately, the band moved from performing in music venues to retrospectives that showcased their albums, “exhibiting” their Musikgemälde in global art institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and Tate Modern in London. The equipment used to create a live mix onstage represents the latest in surround sound technology. Furthermore, since 2011 Kraftwerk have employed 3D technology to create amazing visual effects. Their current performances are striking vindications of their efforts to deliver a 21st-century update of Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk.

The thematic core of Kraftwerk’s artistic project – which draws on sources such as German Expressionist cinema, (Post) Modern architecture, Russian Constructivism, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s experimental music and the Bauhaus – is the notion of the man-machine. The conceptual climax of Kraftwerk concerts is the stage appearance of their mechanical doppelgängers performing the signature song The Robots from the album The Man-Machine (1978). Although they incorporate a large element of irony into their work, Kraftwerk’s oeuvre explores the various interactions between humans and machines as a key feature of modernity. For Hütter and Schneider, there was never any doubt that technology would revolutionise our lives.

With hindsight, it is astonishing how prophetic their 1970s concept albums were in anticipating a future that has become our present. This prophetic quality is even more impressive given that it was delivered through songs that did not so much predict as actually change the musical future. Take the album Computer World. Its cold electronic beats provided the blueprint for the techno music that originated in Detroit. But when the album was released in May 1981, IBM hadn’t yet released the “personal computer” that would revolutionise our everyday lives. What the track Home Computer predicted became reality when the BBC Micro was released later that year: “I programme my home computer/Beam myself into the future.” While Computer Love envisaged the use of digital machines for all sorts of erotic purposes, the title track anticipated the use of technology for surveillance purposes by government agencies.

Kraftwerk’s visionary qualities are not restricted to the realm of cyberspace and computers. Their only UK number one single, The Model (1978), pointed to the rise of celebrity culture, while the Radio-Activity album (1975) raised ecological concerns that were mirrored in German society five years later when the Green Party was founded on an anti-nuclear energy agenda.

In the light of events such as the NSA scandal and the Fukushima disaster, Kraftwerk’s art retains its relevance. The band played Radio-Activity at a recent concert in Tokyo with new lyrics sung in Japanese that referenced Fukushima. Contrary to common perceptions, Kraftwerk never idealised technology. On the contrary, their work was always pervaded by an awareness of technology’s ambivalent nature and potential for creating disaster. It continues to provide a fitting soundtrack to a future that poses more challenges to mankind than technology may be able to overcome.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login