Elysium

Directed by Neill Blomkamp

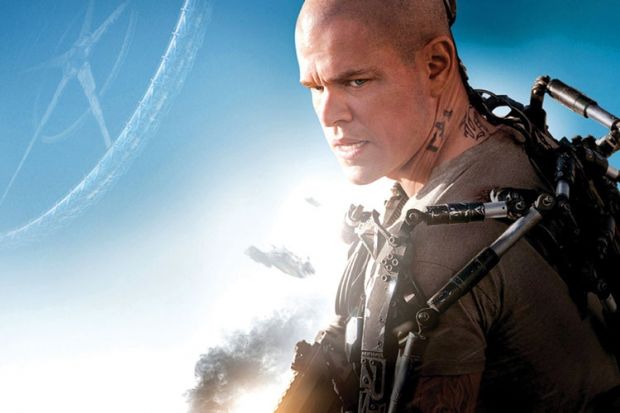

Starring Matt Damon, Jodie Foster and Sharlto Copley

Currently showing in UK cinemas

When I was studying film at the University of East Anglia in the late 1980s, I overheard a conversation between two of my contemporaries. One was explaining to the other that Aliens (James Cameron, 1986) was actually about “the family”. “Oh,” the other student replied in surprise, “I thought it was about Vietnam.”

What is a science fiction action film like Elysium actually “about”? On one level, it is about the simpler pleasures of genre: it is a film set 150 years from now, which revolves around an exclusive space station called Elysium, the poor communities abandoned below in Los Angeles, and one man, Max (Matt Damon), with a mission to make those worlds collide. So there are armouries packed with futuristic weapons: a fleet of surveillance discs, like flying Roombas, nicknamed “the girls”, knives that explode in the victim’s body, and exoskeletons that plug into the nervous system. Elysium shows us people dying in fascinating ways and, more cheeringly, people being healed in fascinating ways, with both processes depicted in lovingly detailed CGI sequences. There’s the spectacle of Damon’s bulked-up body, and extended scenes of brutal hand-to-hand combat in the hard-hitting style of his Bourne trilogy (2002-07). As in most science fiction cinema, there’s the pleasure of special effects that make the impossible look real: military shuttles floating in waves of heat over a shanty town, and a ring-shaped space station hovering in the sky like a wedding band.

On another level, in the background of all the running, jumping and shooting, we can appreciate the intricacy of the film’s mise en scène, and the care with which it builds a convincing future world. The distinctions between life down on Earth and up on Elysium are initially slammed home with cuts between aerial views of dereliction in Los Angeles and smooth cruises over the lawns, pools and mansions of the space station, but they’re confirmed more subtly throughout the film by the characters’ surroundings and belongings. Max’s battered home environment is overwritten with graffiti, and his skin is scored with jail tattoos; by contrast, the space station’s defence secretary, Delacourt (Jodie Foster), uses a Bulgari wrist communicator and power-dresses in structured, ice-blue suits. At work, Max builds the shiny scarlet robots that police Elysium and the ghettos back on Earth, and that gleaming red livery recurs throughout the film, signalling the technology of the privileged classes; the manager of his assembly line drives a Bugatti space shuttle in the corporate colours. Even the exoskeletons are different in the cultures above and below; Max’s, acquired from the LA criminal networks and embedded in his body through backroom surgery, is already scratched and chipped, while the higher-end Elysium models are immaculate, state-of-the-art hardware. Visually, this is one of the most striking “used universes” since Star Wars in 1977, and qualifies Neill Blomkamp as a dream candidate to direct one of the forthcoming Star Wars sequels: and he’d be an ideal choice to film the late Iain M. Banks’ science fiction novels.

The film is also “about” identity. Delacourt speaks French to the citizens of Elysium, but Max regularly uses Spanish, the dominant language of his Los Angeles. Max is branded with tattoos, but his boss, an Elysium exec, also has a facial decoration: neatly raised text on his cheekbone, spelling out “Riche”. As a child, Max is told “never forget where you come from”. Both communities – the ground-level favela and the slowly spinning silver ring that orbits above it – are fiercely proud of their culture, and fighting to protect it.

As with his previous District 9 (2009), the science fiction genre enables Blomkamp to explore structures of cultural inequality and political oppression. Elysium is clearly about class, but it is also about race – Delacourt’s pale, taut white skin is regularly intercut with the sweaty, darker faces of the Los Angelenos – and while, like District 9, it might have most obvious parallels with apartheid (Sharlto Copley, star of the previous movie, reappears as a South African military chief), its themes are also relevant to the contemporary US, where the Trayvon Martin case recently confirmed to many African Americans that the law works in different ways for black and white citizens. More covertly, the film is about health – every character who heads for Elysium is driven by the need to access the space station’s miraculous medical pods – which resonates with American private and public healthcare, and the people with access to each.

At its best, Elysium recognises, and demonstrates, the complex networks of power that operate around cultural identity. More specifically, it shows us a Los Angeles that, unlike Blade Runner’s 1982 vision of pyramids and skyscrapers, convinces as an evolution of the contemporary city. Today’s Los Angeles is not about height but sprawl; not about the vertical but the ground-level spread, and the distinctions between suburb and centre, poor districts and rich. As Edward Soja observed in his essay “Taking Los Angeles apart: Towards a postmodern geography” (1989), the city’s geography is demarcated by wealth and ethnicity, structured by “an essentially exploitative spatial division of labour” where gated communities and private beaches for wealthy white folks are just on the other side of the tracks from Latino barrios, “barricaded in poverty”.

At its heart, this is what Elysium is “about”. Unfortunately, the genre trappings increasingly obscure this core message. The final third of the film is laden with fist fights, scenes of people running down corridors bathed in red-alert lights and doused with sprinklers and, most regrettably, a soundtrack of vaguely spiritual vocals coupled with slow-motion visual sequences. The dialogue, too, becomes more leaden. At one point, Max utters three action-movie clichés in sequence: “I’m gonna get you out of here. I have a plan. We have to split up”, while Copley’s character starts spouting video-game lines such as “You think you can kill me? I’m just getting started”. The film’s conclusion, after the dusty realism and social comment of earlier scenes, is simplistically utopian, and – especially considering the diversity of the casting, which includes Brazilian stars Alice Braga and Wagner Moura, and Mexican actor Diego Luna – disappointingly reliant on a heroic white saviour.

In other ways, Elysium fails to transcend the clichés of its genre. Max, with his shaved head, military gear and bulging muscles, recalls Bane from The Dark Knight Rises, of 2012 (he even lifts an opponent above his head, in the Batman villain’s trademark move). The plot devices of data carried in the brain and downloading information against a countdown are well-worn in science fiction and action movies, and even the underlying concept of rich up on high and poor down below is a common genre trope, dating back at least to Metropolis (19). As such, the social comment of Blomkamp’s vision may be smothered by the time the credits roll. But at its core – with the potential to be foregrounded in a director’s cut – this is a science fiction film that extrapolates convincingly from contemporary cultural divides and projects them into a politically charged future: a film with something valuable to say about the intersections between class, race, gender, privilege and geography. In that respect, it’s about time.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login