Many people walk straight past the homeless: Penny Woolcock stopped and stared (On the Streets, BBC Four, Monday 8 November, 10pm). But what did she actually see? A good deal more than us, evidently. She filmed them for eight months, of which we saw an hour and a half's footage. And that was quite enough. It was like watching people die. I felt guilty getting to the end. Was this cinéma-vérité or voyeurism? Trying to decide was an intellectual indulgence. My emotional perturbation lasted a mere 90 minutes, but the ordeal of the homeless has no end. They must endure until drink, cold or violence does for them. If they are spat on, well, that's a good day. If they're pissed on as they sleep, well, it's better than being set on fire.

Jean was one the doorway-dwellers whose lives washed up before us. Swaying slightly across the embankment, she stopped at the exact spot where a 15-year-old girl had jumped off the bridge into the cold-flowing Thames. "You died, didn't you, baby," she murmured while the well-heeled clicked by with barely a glance. Jean has voices in her head. She was raped at the age of 12 and then again at 16. And a few more times after that. "I'm used to it," she said. "It doesn't bother me now." In fact, she's addicted to it - her word. "I can't wait to get raped again. It keeps the voices happy and at least I'll feel something."

Many of those on the street were abused as children. But Paul was not one of them. He had a couple of maths degrees and talked about the wave-particle duality to a gaunt figure as they waited for soup. One of the ways the homeless fill their days is by joining queues. We did not hear why Paul slept rough. But we did learn why he couldn't stay in a hostel: because his roommate had a habit of crapping on the floor. Paul spent his days in bookshops and his nights on the bus. Jean said she couldn't wait to die. Paul put it slightly differently. "I do want to give up and throw myself on the ground." Only his self-respect prevented him from doing so. Jean had hers taken away from her years ago.

Woolcock's film was as fragmented as the lives it portrayed. We learned a little about some people; nothing, not even a name, about others. If the aim was to humanise the homeless, it was a partial success. If it was to show that they come from all walks of life, it was a triumph. If it was to show why we have so many rough sleepers on London's streets, and how the problem can be solved, it was a failure.

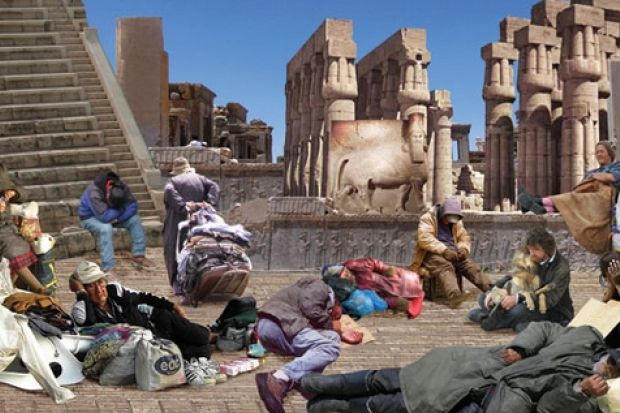

Richard Miles' Ancient Worlds (BBC Two, Wednesday 10 November, 9pm) is a riposte to Kenneth Clark's famous series Civilisation (1969). Widely praised at the time, it was also criticised for its focus on Western Europe. That was apparently due to time constraints rather than any neglect on Clark's part. Whatever the truth, Richard, whose changes of outfit alone make the programme worth watching, begins in the East. The first cities were in Mesopotamia. People came together, he argued, to deal with the common threat of hunger. Grain surplus led to other activities, from music to fortune-telling.

Standing in the ruins of Tell Brak in Syria, Richard held up a bevelled-rim bowl. It was used for a daily ration of food and, in a swipe at Clark, he declared that it was just as significant as the Venus de Milo. Perhaps, but it doesn't have the same power to haunt the imagination. We are drawn to the sculpture partly because of its otherness. But that notion has no place in Richard's concept of civilisation. We are today what we were 6,000 years ago. So he's not only got rid of art, he's got rid of progress (which makes you wonder just what he means by civilisation). I suppose we will just have to keep watching to find out.

Accused (BBC One, Monday 15 November, 9pm) starred Christopher Eccleston as Willy Houlihan, a fundamentally decent man whose life unravels when he finds £20,000 in a cab. A series of mishaps lands him in court. Innocent of any crime, he is guilty of having an affair and it's for that he is punished. A ghostly priest confirms that morality rather than law is at the heart of this drama. The writing, as you might expect from Jimmy McGovern, is taut. Eccleston's performance as a man unable to admit he has lost control of events was distressingly nervy and intense. His character had to be made to realise what was valuable so he could feel the loss of it more keenly. Something with which the homeless are all too familiar.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login