How should scholars decide whether to apply for funding or to accept conference invitations from authoritarian regimes?

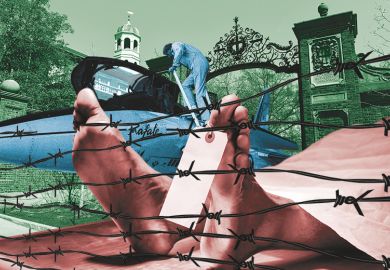

The recent allegation that forced labour has been used on an academic complex in Qatar that houses branches of several Western universities has highlighted the difficult issues faced by higher education institutions with investments in authoritarian states. It led to Alison McGovern, the shadow minister for international development, requesting a meeting with University College London, while UCL said it had “worked consistently” with its partner “to encourage better practice” (“When we travel, our values travel with us”, Letters, 4 September).

Out of public sight and below the radar of human rights organisations, however, individual scholars face similar ethical dilemmas.

Once, the issues of working in repressive contexts presented themselves chiefly in relation to fieldwork. Concerns revolved around the safety of researchers, the potential risk incurred by those who agreed to talk to them, the weight of the questions that went unasked or unanswered and the difficulties of judging the worth of interview data that we knew might have been shaped by fear.

Those dilemmas are, of course, still there. But the rapid shift of wealth and power to the global East and South brings with it a fresh set of ethical issues. Several countries with poor human rights records offer many opportunities for foreign academics. The Qatar Foundation, for example, provides research and conference funding on a very significant scale. Unquestionably close to government, it is chaired by the former Qatar ruler Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Thani and his second wife, and its activities are overseen by a board of directors that includes the Qatari ministers of finance and energy. Its research arm, the Qatar National Research Fund, was set up in 2006 to provide research support for partnerships between Qatari and international universities, with the aim of funding research that meets “the national needs” of Qatar. According to its website, it has funded 78 research projects with UK institutions.

International human rights organisations regularly point fingers at Qatar. As well as the now well-publicised exploitation of migrant labour (also an issue in the building of stadiums for the 2022 World Cup), there are questions about the status of women and respect for their basic rights. Additionally, human rights activists face systematic intimidation: only last month two Britons who were in Qatar to investigate rights abuses against migrant workers were held incommunicado for a week. In these circumstances, should UK scholars take Qatar’s money to fund their research?

There are a range of different strategies that are typically used to counter human rights abuses. One is to work with the governments responsible in the belief that international engagement socialises and leads to better behaviour. Another is to publicly condemn the abuses for what they are, in the hope that it will shame the abusers into doing better. Alternatively, the crimes may be deemed so dreadful that boycott is the only tenable position, lest engagement give the government responsible a veneer of acceptance and legitimacy. Most human rights experts and activists would agree that there is no one right answer and that what works best varies according to context and can rarely be determined in advance.

So how should scholars decide whether to apply for funding or to accept conference invitations from authoritarian regimes? Universities’ vague sets of ethical guidelines are generally unhelpful, and it is not obvious where else to turn for help. It is time for a more energetic debate about the responsibilities of researchers and institutions in countries where human rights are systematically violated. We need to remain open internationally, take our place confidently in the new global economy of higher education and exercise our Enlightenment faith in the value of research and learning as part of the solution to the problems of development, intolerance and conflict. But we must also maintain high moral standards in our dealings with people guilty of grave human rights abuses. How to plot a course through all of that should not be left entirely to individual moral compasses.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login