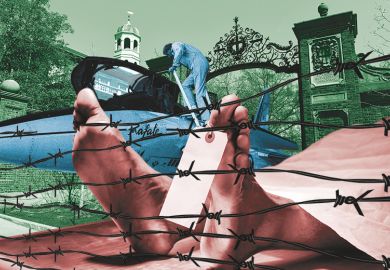

Joanne was pleased to be co-author of a paper with her supervisor – until she found out that an academic she hardly knew had been added as a third author. She thought she was being cheated out of some of the credit. Then she met James, who told her how a year’s worth of his research had been published by his supervisor. James was not even credited as a co-author, and found out that the paper existed only after it was published.

These are just two of the ways that supervisors exploit their research students. Others include using student work as a basis for grant applications, giving talks or media interviews without mentioning student contributions and delaying or preventing students from finishing their degrees to take advantage of their work.

But these are not new problems. Thirty years ago, I interviewed some junior researchers, exploring the dimensions of exploitation. In some cases, it was accompanied by sexual harassment, with productive young women alienated from research as a result.

But the scale of the problem remains unclear, since no one seems to be investigating it now, and specific instances are rarely made public. As far as incoming students are concerned, academic exploitation is a well-kept secret.

Many supervisors are no doubt meticulous in doing the right thing by their students. Indeed, some give their students more credit than warranted to help them get started in their careers. But when supervisors take undue credit for their students’ work, it is effectively a type of plagiarism.

Psychological research confirms Lord Acton’s saying that “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely”. Supervisors have considerable power over students, creating opportunities and temptations to take credit for their work, which may be why some leaders of large labs seem to co-author virtually every paper produced, while spending more time on fundraising than research.

Supervisors are also under a lot of pressure. Funding bodies require proof of productivity and, to obtain grants, the prestige conferred by a superlative publication record is a great advantage. Those who scrupulously refuse to be honorary co-authors may be jeopardising funding for their labs and research teams.

But there are signs of hope. Some journals now expect co-authors to specify their contributions to papers. There is seldom a verification process, but having to spell out contributions can provide a lever for negotiation.

Entry-level researchers are also increasingly mobile. Whatever the negative consequences of this, it does reduce the scope for patronage and exploitation as the competition makes students more likely to assert themselves.

Nevertheless, the problem remains serious, with many new students and junior researchers becoming disillusioned as a result. In a recent article in the Journal of Scholarly Publishing, “Countering supervisor exploitation”, I suggest five responses students could make to exploitation, drawing on my research on strategies against injustice.

Probably the most common reaction is to accept exploitation as part of the career process (from which students can, in turn, benefit when they become supervisors) or change supervisors or drop out of research. Unfortunately, these options do not lead to any change.

Perhaps the most important step is to recognise problems and tell others about them. Exploitation has persisted for so long because it is hidden. Students do not speak out because they fear for their careers if they do, and honest colleagues keep quiet to maintain harmonious collegial relationships. If even a few supervisors or students were willing to raise the issues, others would be empowered.

For students, prevention is better than cure. This means finding out about potential supervisors and avoiding those with a bad reputation, alerting other students to risks, and having discussions with supervisors about authorship before research work is initiated. These steps seem obvious, but are skipped all too often.

Although academics who do not want to put their heads above the parapet could alert students to exploitative colleagues by sending anonymous emails or by writing graffiti on the walls in the departmental toilets, lasting change will come only when honest supervisors take a more open stand against exploitation, informing students of their rights and offering all the advice and support they can.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login