Why do trolls exist? How can such hostile online behaviour be understood intellectually, culturally and socially? Put another way: is the notorious Pedobear character “lulz” (hilarious) or an ambivalent tour guide through child pornography?

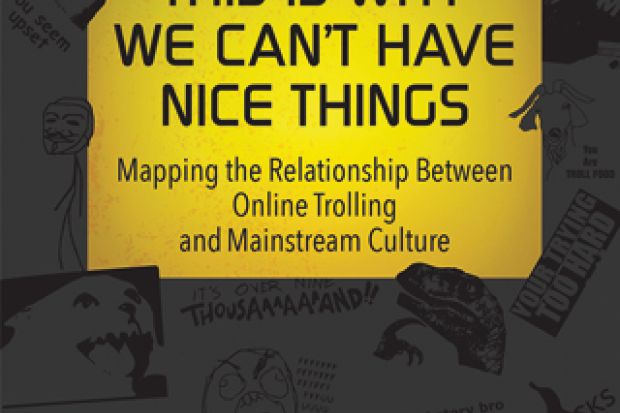

For her recent doctorate, communications scholar Whitney Phillips conducted an ethnography of these groups by entering the trolling subculture. Drawing on that research, This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things considers whether trolling is a deviant subculture or a more universalised online practice. As is common in digital media studies, while Phillips argues for the generalisability of trolling attitudes and practices, her dataset is restricted to the US.

Her book, which will be useful for theorists of digital ethnography, considers the subcultural origins of trolling (2003-07), its golden years (2008-11) as well as a transitional period (2012-15). Phillips is concerned with “the self-identifying, subcultural troll”, drawing a distinction between these practices and simple online cyberbullying. Her challenge was to study this community but not to “replicate trolls’ racist, sexist, homophobic, and ableist output”, which prompts a wider intellectual question about how to create a space for researching social patterns that cause harm to others

“I quite literally had to ‘friend’ trolls in order to observe their behaviors,” she writes. The practices she observed included trolls flooding Facebook memorial pages with callous, provocative messages. On one occasion, she was interviewed on radio alongside a victim of such abuse. She recalls: “The father was distraught and wanted to know why his [late] son had been targeted. He also wanted to know just how evil a person had to be in order to engage in that sort of behavior.” She found herself faced with either defending the indefensible or (somehow) justifying her research: “I worried that I would lose this access if I was too publicly critical, and that I would lose academic credibility if I was too publicly permissive.” Throughout her research, the line between defending and explaining continued to blur.

At its best, This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things shows the value and power of disruption and transgression and the plurality of trolling behaviours. Phillips argues that there are “moments of slippage…between those who troll and those who do not”. Yet the hypocrisy of trolls is clear. They refuse to treat others as they demand to be treated. Anonymity is crucial to trolling discourse. Trolls feed off the over-sharing of other people online. They dip, hook and slice into profound emotional issues. The more public the trolls’ target, the faster and wider abuse travels through social media.

This monograph’s analytical problems lie in the configuration of “subcultures” and “mainstream” culture, the resistive and the dominant, and a lack of theoretical clarity. Phillips argues that “trolls’ behaviors, which are condemned as being bad, obscene, and wildly transgressive, therefore allow one to reconstruct what the dominant culture regards as good, appropriate, and normal”. Such a hypothesis is the equivalent of arguing that Prince Andrew’s air travel demonstrates why the rest of us prefer public transport and private motor vehicles. It misses key steps in the discussion of power, resistance and agency.

Consider the alternative argument. What if trolls are not “engaged in a grotesque pantomime of dominant cultural tropes”, but rather in hurtful, dangerous and illegal activities? Sometimes cruelty is just cruel. Trolls emotionally rape their victims. They locate a weakness – the death of a family member, being bullied or impaired in some way – and then exploit it to hurt, harm and ridicule. Trolling objectifies damaged people to create humiliation and despair and – for a callous few – laughter.

Phillips takes her references from digital media studies, folklore studies, cultural studies, subcultural studies and critical race and feminist theory. But the absence in this disciplinary list is stark and problematic: law. Phillips’ research ignores law, liability, slander and defamation. Yet the troll sites are not as reticent. When entering 4chan, a website that allows images and comments to be posted anonymously, a pop-up agreement must be signed before entry is permitted. This disclaimer states: “This website is presented to you AS IS, with no warranty, express or implied. By clicking ‘I Agree,’ you agree not to hold 4chan responsible for any damages from your use of the website, and you understand that the content posted is not owned or generated by 4chan, but rather by 4chan’s users.” Trolls and troll platforms protect themselves even as they attack others.

Phillips argues for a continuum in which the trolling subculture reflects the mainstream. But an alternative argument is available: sociologists Gresham Sykes and David Matza’s influential 1957 paper “Techniques of neutralization: a theory of delinquency” explains why particular individuals infringe societal rules. They seek out others who contravene norms, and their views become more extreme and disconnected from normative parameters. When applied to trolls, the argument works well. Trolls create an online hive such as 4chan and use this base to swarm the vulnerable. When Phillips invented a fake Facebook profile, she found that “almost immediately, troll profiles began friending other troll profiles…forming an antisocial network of sorts”. It is a swarm built on a technique of neutralisation.

Indeed, her argument that the troll discourse permeates our entire culture can be inverted. When she entered troll culture through ethnography and “went native”, she naturalised the language and abuse in her research and disconnected from mainstream academic culture. The unsayable became normalised. While “LOLing at tragedy” can be seen as a mainstreamed activity, Phillips fails to discuss the social function of cruelty. Erving Goffman’s 1963 study Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity is of much more use in understanding the reasons for this cruelty than Henry Jenkins’ concept of “spreadable media”.

A cliché of online life is “Don’t feed the troll”. Yet to study the troll through ethnography requires feeding, and stocking the refrigerator for future meals. Although this book offers an evocative presentation of the diversity of trolls and troll behaviour, the ethical implications of Phillips’ research should be a key point of discussion for digital ethnographers. She states that “this book is less about trolls and more about a culture in which trolls thrive”. But her definition of culture is narrow: there is no attention to education, media literacy, the changing workplace after the global financial crisis, the precariat, the rise of geo-social networking, the quantified self, changes to the state and – indeed – anti-statism and the evolving regulatory environment of the internet. This is a book that describes the cruelty and nastiness of social media, but the reasons and justifications for such brutality must be found beyond it.

This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture

By Whitney Phillips

MIT Press, 248pp, £17.95

ISBN 9780262028943

Published 8 May 2015

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login