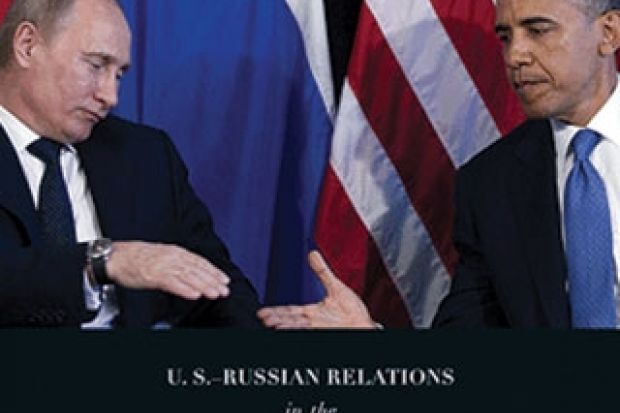

In Angela Stent’s new book, America and Russia are rather like bad ballroom dance partners: constantly stepping on one another’s toes, and both attempting to lead. It’s painful to watch, yet nonetheless encouraging that they keep trying, especially since the grand prize is a safer world.

Between 1945 and 1991, staving off nuclear Armageddon topped almost all other considerations in international affairs. But when the Soviet Union collapsed and Russia redefined itself as a unitary nation state, the spotlight dimmed. A has-been empire with a declining population, Russia found the creation of a “new normal” difficult. From Boris Yeltsin to Vladimir Putin to Dmitry Medvedev, Russian leaders were disappointed in America for not making it easier.

As Stent shows, the US struggled, too. Saddled with major responsibility for world security amid fresh crises in the Middle East – followed by a drastic economic downturn – American presidents found it hard to perform their own duties while satisfying Russian leaders’ craving for greater respect and a bigger role.

Stent, a Sovietologist who served in government under presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, expertly condenses the past two decades of this tumultuous relationship with an insider’s command of detail. She explains complex events between 1991 and 2013 from the perspective of both nations, arguing that policies mostly transcended personalities. Indeed, historians might observe that the crux of Russian complaints even transcended the post-Cold War period. From Stalin forward, Russian leaders consistently expressed the opinion that Western leaders, particularly Americans, failed to appreciate their legitimate security concerns. What made this complaint hard to address was that Russians often defined these interests at the expense of neighbouring countries and internal dissidents.

Nonetheless, Stent shows that both countries strived mightily for a better partnership after the Cold War. She points out that Putin was the first foreign leader to call Bush after the events of 11 September 2001. Putin offered not only heartfelt condolences, but also practical help of immense importance. Despite resistance from other Russians, and even against his initial predilections, he facilitated the establishment of American military bases in former territories of the Soviet Union, namely Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, to support the US in Afghanistan. Given Russia’s historical xenophobia, this magnanimity was astounding.

The US, for its part, blessed Russia’s inheritance of the USSR seat on the UN Security Council, gave billions towards the peaceful denuclearisation of Ukraine and Kazakhstan, supported Russia’s application to the World Trade Organisation, and moderated its critiques of Kremlin policy towards Chechnya in light of terrorist attacks on the Russian public, including schoolchildren.

Yet despite efforts to achieve a better rhythm, coordination has been elusive. Washington ignored Russia’s seasoned advice on the perils of rising terrorism, to its sorrow. The US Congress’ confrontational streak also frequently impeded diplomacy. In 2012, it finally lifted its Jackson-Vanik trade limits against Russia – more than 20 years after the Soviet Union stopped restricting immigration – only to substitute it with a new criticism of Russian human rights inadequacies, the Magnitsky Act. Like his predecessors, Putin is especially allergic to foreign pressure on domestic matters.

Russian retaliation for these and other perceived slights has been swift: from calling the US on its hypocrisies, to expelling American “spies”, to limiting the access of foreign non-governmental organisations, to denouncing the expansion of Nato.

At base, however, Stent faults an ongoing lack of structural ties for perpetuating volatility. Trade with Russia is only 1 per cent of total US trade, limiting the private sector’s ability to act as ballast and calm political reactions. And the West as a whole has failed to think creatively enough about how to include Russians in the “institutions that regulate European security”, keeping them on the outside, noses pressed to the glass. Of course, she admits, Russians aren’t enthusiastic joiners either.

Stent’s book sometimes reads like a State Department briefing. Empathetic and informational, it advances few controversial interpretations. Newspaper readers who dozed off occasionally over the past 20 years will find it an illuminating recapitulation of key events and personalities. This book’s best news is that both sides in the limited partnership recognise the relationship’s import. The long-term trend is far more positive than negative, and Russian-American goals are not fundamentally misaligned. Now if they can just stay off one another’s toes…

The Limits of Partnership: U.S.-Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century

By Angela E. Stent

Princeton University Press, 384pp, £24.95

ISBN 9780691152974

Published 29 January 2014

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login