The discovery of unsung heroes is one of the rare silver linings in the history of the Second World War. And Gertrude van Tijn was certainly a hero. German-born, married to a Dutchman, and a fluent English speaker, van Tijn was trained as a social worker in Berlin by the German Jewish feminist Alice Salomon, and made stump speeches in London for the suffragette cause. Forced to leave England during the First World War, she settled in Amsterdam and became involved in the Zionist movement. From 1932 she ran the department of social work at the Dutch Council of Jewish Women. This work enabled van Tijn to save the lives of thousands of European Jews, by organising their emigration from Nazi-controlled Europe.

She refused multiple opportunities to escape the Netherlands after Germany’s occupation, preferring to try to facilitate emigrations and offer practical support to Jews being deported “to the east”. Amazingly, the legacy of this rescue work is not uncontroversial. Bernard Wasserstein deftly describes the tensions between the council and its constituents. As Nazi oppression intensified, many Jews viewed the council as either acquiescing to or, worse, collaborating with the German occupiers.

Van Tijn distanced herself from the council’s two leaders, who were either extremely naive or too keen to ingratiate themselves to authority, however morally dubious that authority was. In one chilling scene, Wasserstein describes the leaders actively performing the Nazis’ dirty work, selecting their own employees for deportation, while more junior colleagues obfuscated.

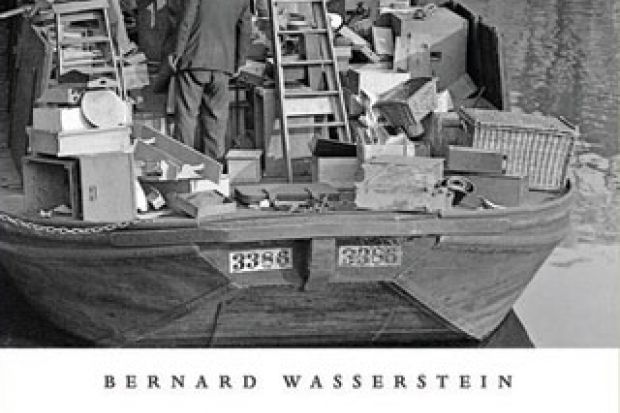

Why van Tijn continued her work with the council rather than intensifying the more radical and even illegal approaches she took to rescue Jews (including helping to organise the sailing of the Dora, a coal ship, to Palestine) remains unclear. Perhaps she felt she could do more this way. Perhaps she was more comfortable working within her own upper-middle-class milieu. Wasserstein does not make this clear.

No clearer is why one council leader spent the post-war years trying to ruin van Tijn’s reputation. Ostensibly this was because of her refusal to be held responsible for the council’s collaborationist policies. Van Tijn provoked strong reactions among men – many loved her, either platonically or romantically. But her male council colleagues were always cold. Why? Frustratingly, Wasserstein seems reluctant to speculate. Was her status as an unconventional, independent career woman as threatening to her male colleagues as her readiness to stand up to the German occupiers? We don’t know.

Nor do we know much about her community, beyond the inner political wranglings of the council. Statistics can take us only so far into the horror of the Third Reich; Wasserstein’s numbers of Jews deported are shocking but ultimately less viscerally moving than tales of individual suffering. Wasserstein mentions that during the council’s selection process, a young boy, who saw his own name on a list, “ran away in terror”. I wanted to know his name.

What we do understand better for having read this book is that a stubborn blindness to immediate danger and an eerie prescience of disaster existed concomitantly in European Jewish communities. Despite Jewish council leaders sometimes blithely cooperating with their Nazi oppressors, few within this community were blind to their future. Van Tijn used the word “extermination” in 1938 when referring to the Nazis’ plans for German Jews. While Wasserstein says that van Tijn “could not envisage…the mass murder of German Jewry”, it’s an extreme choice of words. In early 1941, a colleague of van Tijn’s stated bluntly that “the Germans intend to kill us all”. What is most tragic in this story is the inability of the Jewish community to alert its gentile compatriots, many of whom were hugely sympathetic, to their desperate plight.

The Ambiguity of Virtue: Gertrude van Tijn and the Fate of the Dutch Jews

By Bernard Wasserstein

Harvard University Press 352pp, £20.00

ISBN 9780674281387

Published 24 March 2014

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login