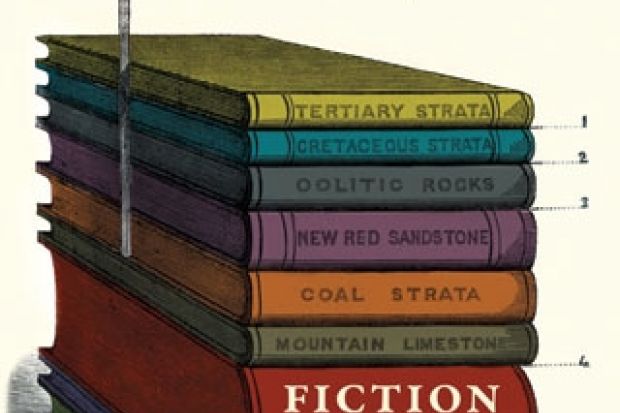

In 19th century Britain, the study of the ancient earth gripped the public imagination.” Thus begins this remarkable book, and its claim is very true. For geology began as a British science, at least in part because not only was all the vast British coastline ripe for geological exploration, but also because canals were being excavated, quarries dug and deep mines exploited for coal, exposing so accessibly the geological treasures of this land, including its ancient life forms. The founding fathers of geology built on this great resource in developing geological concepts and these, which had become so popular in Britain, spread rapidly to the Continent and further afield. The concept of an ancient Earth became part of the public understanding, aided by new geological maps, sections and often large-scale exhibitions. But above all, as argued in the first part of this volume, it was literature that dramatically influenced the pervasiveness of geological thinking. For “if science was literature in the 19th century…then that literature was science too”. This is the really important concept developed here. The fathers of geology were all literary men. They wrote eloquent, if by modern standards flowery, prose. And even though the writings of James Hutton were almost impossibly convoluted, his friend John Playfair, with his superbly developed literary skills, made his arguments easily comprehensible.

The fathers of geology were all literary men who wrote eloquent, if by modern standards flowery, prose

The chapters in the first section, Stories in Science, explore the intellectual atmosphere of the first part of the 19th century, and the lives and contributions of the major geological players. They give a fascinating account of the interplay of literature and geology as the science developed. The great geologists of the time – Hutton, William Smith, Charles Lyell, William Buckland, Roderick Murchison, subsequently Charles Lapworth and so many others – worked empirically; and whereas they described what they saw and what they could properly interpret inductively, rather than mega-theorising (“arm-waving” in modern parlance), they provided a secure foundation for large-scale theories later on. The early British geologists knew their Dante and their classics, but they had also read and admired the works of Sir Walter Scott. Indeed, as argued here, the imaginative literature of Scott gave them a language with which to express themselves and they wouldn’t have done so well without it. This first section surely repays a second reading.

Not only did literature influence geology, but geology books entered literature, too, and in the second section (Science in Stories), three literary figures are singled out for special mention. Charles Kingsley is considered at greatest length; he had had an intense interest in geology since boyhood and was a positive Darwinist, but fascinated by violent geological cataclysms. His Madam How and Lady Why, a geological primer for children, influenced me exceedingly when I was a boy. Here it is Kingsley’s novels that are analysed, above all; the terrifying volcanoes that his protagonist Alton Locke sees in a feverish dream have a spiritual meaning, too. The other writers are George Eliot (less convincingly portrayed) and Charles Dickens, with his monomaniac geologist Professor Dingo in Bleak House.

This is a scholarly work, with 95 pages of footnotes and index following 282 pages of text. There are eight fine coloured plates of historical geological maps and sections. Although I found it more sharply focused in some parts than others, with the links between some of the sections requiring a second or third reading before I could properly understand them, this fascinating book introduced me to perspectives that neither I nor most geologists have ever really thought about. But as a result of reading this mind-expanding book, I am thinking about them now.

Novel Science: Fiction and the Invention of Nineteenth-Century Geology

By Adelene Buckland

University of Chicago Press, 400pp, £31.50

ISBN 9780226079684 and 6923635

Published May 2013

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login