Sir Edgar Speyer (1862-1932) was born in New York of German Jewish descent, worked in Germany in the family banking business and came to England at the age of 24, where he settled into a successful life of business and philanthropy. He took British nationality in 1892 and was rewarded for his generosity to his fellow citizens with a baronetcy in 1906 and membership of the Privy Council in 1909. By 1922 he had been stripped of his citizenship, as were his three daughters, who were all born in England. Antony Lentin has written a well-researched, compelling and balanced account of a remarkable life and explains clearly how a widely admired public figure was turned into an object of hatred and derision. He has, in the process, done justice both to Speyer and to his more responsible critics, while leaving the reader in no doubt about his opinions of the vile behaviour of the xenophobes and anti-Semites who were the real authors of his subject’s downfall.

Speyer did much that was applauded, not least by the press. He rescued the Underground Electric Railways Company of London from bankruptcy, using his bank’s funds to stave off creditors. He saved Henry Wood’s Promenade Concerts by underwriting their losses and gave generously to the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. In London’s impoverished East End, he founded the Whitechapel Art Gallery and financed Toynbee Hall and Poplar Hospital. In 1904 a penny savings bank in Suffolk failed and he rescued it with his own money, an act commended by the Pall Mall Gazette as worthy of celebration by Charles Dickens.

But he was of German ancestry. When war broke out in 1914 and dachshunds were kicked in the street, his good works counted for nothing. The loathsome Horatio Bottomley (who was soon to be jailed for fraud) proposed that naturalised Germans, like Speyer, should wear a badge, an idea later taken up by Hitler for Jews. The leaseholder of the Queen’s Hall, where the Promenade Concerts were held, condemned Speyer as “notoriously German” and proposed to ban German music. Wood replied: “There is no nationality in music.” The popular press, led by the Northcliffe newspapers and as spiteful then as it is now, began an agitation that drove Speyer and his daughters into exile in the US and led to a public inquiry. It concluded that Speyer had been friendly with a distinguished German conductor in Boston (where Speyer had gone to live because it reminded him of England); that he had illegally made contact with members of his family in Germany and with a handful of friends there who were in financial distress; and that he might have wanted to settle in Germany after the war. Who would have blamed him? His former admirers on the Pall Mall Gazette headlined the committee’s findings as “the Unmasked Hun”.

A man may be judged by the friends and enemies he makes. Besides Wood (who said he could not recall Speyer’s kindness “without a lump in my throat”), his friends and admirers included an impressive roll call of his contemporaries: Edward Elgar, Winston Churchill, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, George Bernard Shaw, Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy, Richard Strauss, Percy Grainger and Robert Falcon Scott, whose polar expedition would never have sailed without Speyer’s support. Most remarkable was the reaction of George V, who would not accept Speyer’s resignation from the Privy Council and whose outraged reaction to the proposal to arrest him was unequivocal. Referring to his own German ancestry, the king cried: “Let them take me first. Let me be interned before Speyer.” Speyer’s enemies, besides Bottomley, Northcliffe and the press hounds, included the despicable Noel Pemberton Billing, MP for Hertford, who denounced him in the House of Commons under parliamentary privilege.

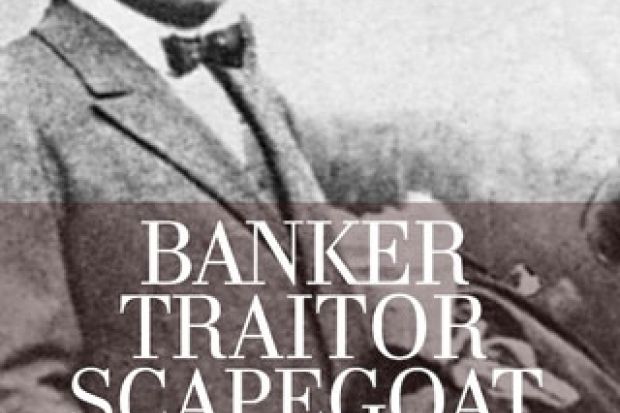

Although Scott named an Antarctic mountain after Speyer, Lentin, who is understandably sympathetic towards his subject, laments that there is no blue plaque at 46 Grosvenor Street in Mayfair to mark the home of the Speyer family. There should be. The inscription should reflect the title of this engaging and original book, which records one of the forgotten tragedies of the First World War: “Sir Edgar Speyer, 1862-1932, banker, philanthropist and scapegoat”.

Banker, Traitor, Scapegoat, Spy? The Troublesome Case of Sir Edgar Speyer

By Antony Lentin

Haus Publishing, 256pp, £12.99

ISBN 9781908323118

Published 8 March 2013

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login