This is a generous, well-crafted review of the life of Bradford-born public sector architect Mary Medd (née Crowley, 1907-2005). As a means of gaining insight into how to design schools, Catherine Burke’s book beautifully illuminates her subject’s profound impact on the thinking and processes involved.

Medd’s humility as a collaborator and educator alongside her husband David (with whom she shared both credo and craft) allowed her to “stoop to conquer” and influence peers and educational professionals alike. She believed that good architecture emerged only from serious attention to “process” - that is, from detailed attention to defining the enquiry (learning transformation) and not just the solution (beautifully designed schools).

Her conviction was that only a deep understanding of education could result in transformative and pedagogically informed architecture. Instead of defining herself as an educational planner first and a designer second, her approach made her a champion of their convergence. For Medd, the two practices had to be considered together and their separation represented a false dichotomy.

Serious educationalists committed to serious learning can and do design in ways those less committed to pedagogy simply cannot

Burke, a historian of education, shows mastery of her subject here and delivers it through a light, accessible style. Over the years, she has demonstrated an expansive enthusiasm for innovation in teaching and for the design of formal and informal learning spaces. Medd becomes Burke’s touchstone - her avatar, even - in enabling the articulation and extension of her thinking and brilliance in this field of enquiry.

The Brazilian novelist Paulo Coelho once observed: “I’m modern because I make the difficult seem easy, and so I can communicate with the whole world.” This statement nicely captures Medd’s philosophy and practice of architectural accessibility - and Burke’s project here.

Moreover, as Burke implies, it is possible that Medd would see growing obscurantism in architecture as mere cant and a form of pseudo- intellectual indulgence. What she wanted to enable was interdisciplinary collaboration that could be understood by the wider community, not only the architectural elite. The ability to collaborate and communicate with clients is an enduring preoccupation in architecture, particularly in a time of economic crisis where architects and educators alike struggle to effectively articulate the value of some of our beyond-the-building expertise.

The “process” part of our expertise is arguably what today’s architects utilise least. As Burke illustrates, Medd’s work served to demonstrate how “design thinking” is far more expansive than mere materials, since it embraces - or rather, should embrace - how we design collaborative processes that empower clients and communities to shape their environments.

Appropriately - and perhaps also ironically - Medd’s educationalist sensibilities empowered her real-world design prowess and practice. The cliché that “those who can’t, teach” is thus inverted: serious educationalists committed to serious learning can and do design in ways those less committed to honest pedagogy simply cannot. To have the career and contribution of Medd’s architecture recognised by Burke in this way, particularly by someone outside the discipline, is an important acknowledgement of the significance of the former’s work.

This study was written prior to the closure of the UK government’s Building Schools for the Future programme. Had it continued, the book could have served as a powerful point of application for architects keen to resource their school design proposals through understanding the origins and legacies of the Medds’ transformative learning environments.

Burke’s book offers everything from an education and practice manifesto to a compelling romance. The narrative overlays within the text capture valuable insights into the infrastructure of key design projects, including clients, creative collaborators and educators working towards a common enterprise. As Burke observes, “architectural history need not be just about buildings or architects but can also be about compelling relationships, values and how these inform the process of architectural practice”.

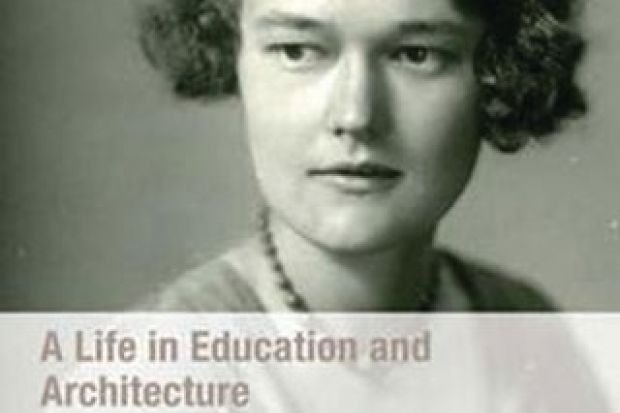

A Life in Education and Architecture: Mary Beaumont Medd

By Catherine Burke

Ashgate, 292pp, £55.00

ISBN 9780754679592 and 9781409471905 (e-book)

Published 14 January 2013

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login