Source: Elly Walton

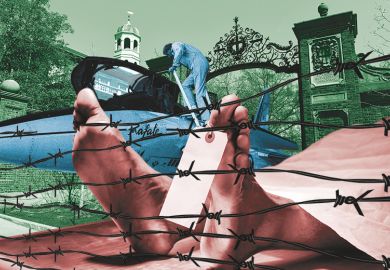

The multimillion-pound process used to assess the quality of university research has been described as “a Frankenstein’s monster” that must be kept under control at all times. But with 12 months to go until the cut-off point for the inclusion of staff in the research excellence framework, it seems that the monster is unbound: academics report that the sector is engaged in a “feeding frenzy” as universities hunt down and attempt to poach leading researchers in time for the submission deadline.

Their incentives for doing so are clear. The publications brought in by star researchers can boost departmental REF scores, which will be used to distribute hundreds of millions of pounds (a total of £1.6 billion in 2012-13) in public funding. The best performers will attract the most cash and prestige.

Stefano Fella, national industrial relations official in the higher education department at the University and College Union, says that UCU members can offer many examples of top researchers being parachuted into their universities (often with high pay and low teaching responsibilities) specifically for the REF.

“It’s a common complaint, particularly in…middle-ranking universities, which are trying to propel themselves into the higher echelons of the research league tables,” he says.

Information collected by Times Higher Education through a Freedom of Information request confirms this pattern. Although many institutions have gone on hiring sprees in the past year, it seems that the elite inside the so- called “golden triangle” of Oxford, Cambridge and the research-intensive universities in London may be less involved in the frantic scramble because their staff are already expected to have excellent research track records.

THE asked universities for details of the number of staff who carry out research and were hired on salaries above £40,000 - a good indication of likely inclusion in the REF - in 2011 and 2012.

At University College London, the number of academic staff recruited in this income bracket was lower in 2012 than in 2011. David Price, UCL’s vice-provost for research, says that the institution’s hiring policy is not directly related to its REF strategy.

“It’s business as usual for us,” he explains. “We use the same criteria now as at any time and our aim is to attract leaders at whatever stage they are in their careers.”

But other institutions tell a different story. The University of York has increased its intake of new research staff by 57 per cent this year - from 77 to 121 - while Sheffield Hallam University has almost doubled its intake from 22 to 40. At the University of Surrey, numbers have soared from 84 to 140.

There have also been huge increases at smaller institutions: Bath Spa University has more than quadrupled the number of senior researchers it has taken on, from six to 26, while Glasgow Caledonian University has hired 17 staff in this category compared with just two in 2011.

On average, across the 96 institutions that responded, recruitment of staff in this income bracket rose by 23 per cent. Among the 1994 Group it rose by 51 per cent and among Million+ universities it rose by 44 per cent.

Drawing in the best researchers ahead of an assessment exercise is certainly nothing new. Reports suggest, however, that hiring decisions are increasingly being dictated by central management.

Some also believe that the decision made in 2010 to cut quality-related (QR) funding for 2* research, defined as “internationally recognised” in the coming REF, has intensified the pressure.

To become one of the 25 fellows the University of Birmingham plans to hire by the end of the year, for example, candidates must have a publications record “such that they will be able to submit 3-4 publications of a 3* (international quality) or 4* (world-leading) level” to the REF, according to details posted on the university’s website.

“New hires” are often expected to have already met such standards. Staff who spoke to THE anonymously reported that in some cases, all bar the earliest-career researchers are expected to have written publications of this quality.

Meanwhile, factors that are otherwise deemed important, such as teaching ability or success in attracting seed funding for bigger grants, take a back seat.

“During hiring, in my department at least, the REF was the filtering mechanism - so people not only had to have four ‘REFable’ pieces, they also had to have them in hand a year ago. Only then were secondary criteria employed,” one postdoctoral researcher explains.

When embarking on “fishing expeditions” to poach researchers, universities attempt to offer attractive recruitment packages to lure staff away (see box below). Increasingly, according to the academics who spoke to THE, these packages include lightened or non-existent teaching loads, with pedagogic responsibilities shifted on to the shoulders of existing staff or doctoral students.

One academic, who asks not to be named, reports that his institution recently hired 15 professors who are not required to do any teaching. “Since most of our income is from teaching, and the [university’s] mantra is about research-led teaching…that is odd to say the least,” he says.

Another way in which institutions are seeking to bolster quickly the ranks of their top researchers is by using a single rolling notice for multiple posts. But critics say this practice allows management to “cherry-pick” staff and avoid a standard selection process for each position.

“Where recruitment isn’t transparent, that is a problem,” says Fella. “When posts and the role to be performed aren’t specified, it can be difficult for potential applicants to know whether they are eligible. [The practice] may favour people in the know, who have been informally tapped up.”

Parachuting in staff on a short-term or part-time basis is another way of bending the rules, academics report.

Under Higher Education Funding Council for England regulations, an institution need employ an academic for only one-fifth of the hours of a full-time equivalent post for their research publications to be included in the REF.

Although the QR funding distributed as a result would be proportionately smaller, many institutions are driven to explore such options by the desire to boost their reputation through higher scores.

“There are a number of one-day-a-week positions being offered,” reports one academic. “One person I know is being hired by a London university on a contract that involves going in for just a handful of days a year, just because they want to include his REF publications.”

Earlier this year, the School of Management at Royal Holloway, University of London advertised for five professors to work at the school, each with a contract effectively meaning that they would work there one day a week.

Jeffrey Unerman, head of the school, points out that the posts - four of which are now filled - are permanent and that the new staff will be encouraged to play an active role in the life of the institution. He emphasises that they were hired as part of a long-term strategy.

“Some would argue that if an institution were looking to tactically recruit for REF purposes, [it is] likely to do so on a temporary basis with contracts terminating shortly after the REF census date,” he says.

On the flip side, researchers who do have the requisite number of outputs are using the REF’s “flurry of jobs” to their advantage, one early-career researcher indicates.

“If you’re on top of your game and have got some good pieces, it’s a really good way of navigating some troubled waters - it gives you a bit of agency.”

Some younger scholars, particularly those whose careers have been formed in this culture, are beginning to plan their work accordingly, she adds.

Researchers who started their careers on or after 1 August 2009 are allowed to submit fewer than four outputs without penalty. But recent PhD students, who might lack the output to make the most of this round of hiring, may want to think about holding back publication until after the submission date, she explains.

“If you do have years ‘in the wilderness’, at least when you go into the market the next time around you will have a strong hand to play.

“These kinds of [recruiting] practices are massively problematic and we would [prefer] not to live under them, but we do and it’s stupid if you don’t act strategically.”

The REF could have a longer-term impact: the hiring frenzy it has triggered constitutes a spending spree that may take its toll on recruitment for years to come, suggests the head of one research council institute who has been watching proceedings closely from the outside.

“What happens for the two years after 31 October 2013? For the talent that’s coming up, places will be frozen, departments having used up their budgets. What about that next cohort of people who I think will be disadvantaged, who haven’t quite managed to mature their careers in time?” he asks.

So can and should anything be done? Or is the flurry of recruiting activity in the run-up to the REF acceptable or even desirable? If so-called REF “gaming” is skewing submissions, Hefce hopes that it will be able to pick up on it.

For example, the funding council plans to compare the profile of staff submitted with the eligible academic population to uncover inconsistencies, explains Graeme Rosenberg, REF manager at Hefce. How Hefce would deal with such inconsistencies remains unclear, however.

Concerns have been raised in almost every previous assessment exercise about excessive turnover but Rosenberg says there is no evidence to back them up.

“We do regard a certain degree of turnover as healthy,” he says. “Actually, in the year before the [final] research assessment exercise [the REF’s predecessor, held in 2008], there was only a small increase in turnover - nothing so much that it concerned us.

“I think you are hearing similar stories this time around. We’ll have to wait and see if it is any different.”

Ian McNay, emeritus professor of higher education and management at the University of Greenwich, conducted a study on the first RAE, Impact of the 1992 RAE on Institutional and Individual Behaviour in English Higher Education, in the mid-1990s that was published in 1997. The study showed that the recruitment of “research stars” was not particularly successful.

“One former poly recruited the whole of a research group but then had to recruit other staff because postgraduate students complained about the terrible teaching quality of the researchers,” McNay recalls.

Writing in Can the Prizes Still Glitter?: The Future of British Universities in a Changing World (2007), Eric Thomas, now president of Universities UK, claimed that institutions had invested more in securing research stars for the 2008 RAE than they could recover through increased QR funding.

But the benefits to an institution of being able to claim a prestigious department with a top RAE/REF score - increased student recruitment, better pulling power for top staff and external grants - are more difficult to quantify.

What of the changes to the methods used to assess the quality of research? The most hotly debated element of the REF has been its requirement that departments demonstrate the “impact” of their research - its benefits to the economy, society and culture beyond the academy. According to some, this may reduce the value of last-minute hires.

If a member of staff moves institution, any of their publications dating back to 1 January 2008 can be entered into the REF. However, evidence of impact can be submitted for assessment only if the research took place when the academic in question worked at the new institution, Rosenberg points out.

Despite having “serious concerns” about the impact requirements, the UCU agrees that this is one area where institutions can hire only for long-term rather than short-term gain.

“One possible advantage [of the new system] is that it does oblige institutions to look at their existing staff and [impact] is not something that can be brought in at the last minute,” says Fella. “That does lead to greater value being placed on staff within an institution.”

Ultimately, while adopting a short-term REF strategy may pay off in terms of funding and prestige, “playing the game” can damage teaching and longer-term research, and end up doing more harm than good, he argues.

The finest departments have a strong research identity and teaching ethos that come from staff working together over a long period of time, agrees one London-based lecturer.

She adds: “Magpie-ishly collecting an array of shiny academics for REF purposes doesn’t make a brilliant department.”

Movers and shakers

Lisa Jardine: Queen Mary, University of London to University College London

In September, the former centenary professor of Renaissance studies at Queen Mary left to become the first director of UCL’s flagship Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in the Humanities - and took her entire team with her.

Fay Weldon: Brunel University to Bath Spa University

The author’s recruitment as professor of creative writing is among 16 high-profile appointments made by Bath Spa as part of a “wider programme of development and growth”. Also among the new professors who will be in place by the end of 2013 are visual artist Gavin Turk, composer Joe Duddell and novelist Tessa Hadley. Christina Slade, the university’s vice-chancellor, accepted that the appointments were “not entirely divorced” from the REF.

Graham Reed: University of Surrey to University of Southampton

The scientist moved the research group in silicon photonics he set up at Surrey in 1989 to Southampton earlier this year. Reed attributed his decision to the university’s eagerness to develop the field and the facilities it has to offer, including a £120 million high-tech laboratory complex.

David Leigh: University of Edinburgh to University of Manchester

Earlier this year, Manchester poached organic chemist David Leigh and his team of nearly 30 scientists from Edinburgh to work on the development of advanced artificial molecular machine systems. To support the appointment, the university undertook a £4.1 million refurbishment of its chemistry building.

Mark Leake: University of Oxford to University of York

The group leader in biophysics at the University of Oxford is an expert on single molecule cellular biophysics. He is expected to move to York as one of 16 anniversary professors, announced in July. The academics will be recruited across a range of fields as part of the celebrations to mark York’s 50th birthday.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login