Tatsumi

Directed by Eric Khoo

Starring Yoshihiro Tatsumi and Tetsuya Bessho

Released in the UK on 13 January

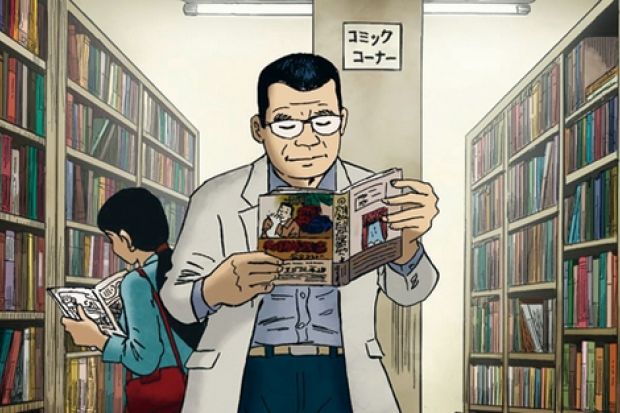

This week sees the release of a film based on the life and work of Japanese illustrator and storyteller Yoshihiro Tatsumi. Tatsumi is a cinematic adaptation of the manga artist's memoir, A Drifting Life, and five earlier short stories, Hell, Beloved Monkey, Just a Man, Good-Bye and Occupied; it premiered in the Un Certain Regard section at last year's Cannes Film Festival and has already been selected as the Singaporean entry for Best Foreign Language Film at the 84th Academy Awards. A Drifting Life won the 2009 Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize, named after the godfather of Japanese anime, and Tatsumi's haunting reflection on the modern condition, alienation and post-war life in everyday Japan will no doubt inspire a new generation of anime fans across the world. Unlike the mythical worlds of Hayao Miyazaki (Howl's Moving Castle, Spirited Away, Porco Rosso), Tatsumi is well known for his elliptical, minimalist vision, which tends to have more in common with the adult novels of Raymond Carver or Haruki Murakami rather than the fantasy realms of Lewis Carroll or Roald Dahl. Tatsumi serves not only as a timely celebration of one of Japan's most gifted artists but also, more generally, invites reflection on the impact of anime on the cinematic medium and the evolution of the anime genre.

In one of Tatsumi's most striking sequences, a young, unnamed military photographer is seen holding his camera up to the ruins of Hiroshima, clicking away as if possessed. Navigating the rubble and debris, charred bodies and crumbling homes, the young photographer glimpses an opaque image, a shadow, and he explains to us that "the bomb's powerful flash had imprinted someone's shadow into the stairs of Sumitomo bank". We also see the "shadows of the spiral staircase" and, most troubling of all, two figures mistaken as the image of a son giving his mother a shoulder massage (later revealed to be a crime scene). This sequence draws on Tatsumi's Hell, and its figuration in the first few minutes of the film sharply establishes the tonal and structural style of the entire feature. As with Hell, viewers drift between the fictional creations and the illustrator's real-life events, beginning with his childhood and, of course, the first publication of his manga comic Children's Island in 1954 in which the "scent of the new ink" made him high. Thus, the linear chronology of Tatsumi's life is intercut with interludes from his comic books, signposted through the use of differing colour schemes. This particular combination of fiction and non-fiction tends to emphasise the autobiographical elements of the film as an extension of Tatsumi's melancholic, comic universe.

In another interlude, a factory worker laments the post-war modernisation of Japan and its unrelenting labour-driven economy. While he waits to be crammed "like a sardine" into a train, he appears to be lost in thought, his mouth agape, and a voice-over muses: "the more people flock together, the more alienated we are". Indeed, Tatsumi created a new form of anime, separate from the original manga style, more adult in tone and in its use of realism, coining the term "gekiga" - dramatic pictures. Noirish, Edward Hopper-esque and deeply involved in examining the social, political and sexual implications of post-war Japan, gekiga was a landmark genre of manga that challenged the conventions of its predecessors. The manga comic industry was already hugely successful when Tatsumi first began working as an illustrator, but while he admired Tezuka's work, he wanted to capture the feel and mood of Japan's rapidly changing social and political landscape. Tezuka's Astro Boy television series was extremely popular, but owed much to Disney and its whimsical narratives; Tatsumi created witty "slice of life" short stories inspired by Hitchcock and pulp fiction, early 20th-century American fiction and Hollywood cinema. Tatsumi's characters invariably represent a generation of workers and students, loners populating the everyday - fleeting glimpses into an otherwise silent majority.

While Tatsumi's commentary on Japanese culture is peppered with gritty, American visual cultural references, Hollywood has also borrowed, more broadly, from manga's unique aesthetic. Paying explicit homage to manga in the Kill Bill series of films, Quentin Tarantino's fascination with Japanese anime is felt acutely not only through the use of a manga-style sequence in which live-action characters are transformed into animated icons, but in the overall dynamic visuality of the films, especially their action sequences and the narrative's focus on a female heroine. Frank Miller's work with DC Comics also conjures the erotic and dangerous pleasures of manga fiction, borrowing the multi-layered, structural styles and motifs familiar to all manga readers. While films such as Akira (1988), Fist of the North Star (1986) and Ghost in the Shell (1995) are now critically acclaimed as classics of the genre, the global success of the more recent live-action version of manga's Oldboy (2003) has prompted Hollywood to revisit the material, a move currently being orchestrated by Spike Lee.

Manga represents an evolutionary step beyond the "floating world" of Japanese art depicted by the traditional woodblock prints or engravings known as ukiyo-e, transposing the beauty of such images on to paper and celluloid and re-imagining them as vital experiences, kinetic and electrifying. Indeed, as Philip Brophy writes in his impressive 100 Anime (2005), "If anime is a body, no existing medical practice is suited to examining it"; we are, as Brophy's book implies, entering a new age of visual culture whose shape embodies unknown, and hidden, desires that modern living has repressed. Tatsumi's illustrations are testament to the dreams and nightmares of the modern subject and their vivid worlds drift among shadows as well as light and laughter.

Like the imprint of the shadow in Tatsumi, hovering indefinitely on the wall of ruins in Hiroshima, the legacy of Japanese animation has called attention to the hidden layers of reality, and truth, that images can bring forth. In the age of the digital image, YouTube and instant photo messaging, we are compelled to construct our own narratives from the raw and disposable fabric of our own, everyday lives. Tatsumi's comics bear witness to history, but they also pay tribute to minor events, moments lost for ever in the humdrum existence of the labour worker, the student, the train passenger, the projectionist, the sperm donor, the TV personality.

At the end of Tatsumi, the illustrator is seen at his desk drawing. Soon, the animated image transforms into live footage. Tatsumi reflects: "There are so many worlds I haven't drawn yet..." Perhaps, as we are faced with the non-animated image of the illustrator, we are forced to question his perception of human life - to what extent his drawings help him to make sense of what might seem to be an indifferent and uncompromising reality. Certainly, Tatsumi reminds us of the connections that exist between all of us, and our universal need to communicate ideas and knowledge, despite cultural differences. For those who venture into manga territory, such worlds become deeply embedded in the psyche of the reader/viewer and this experience transcends any language or cultural barrier.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login