The Silence

Directed by Baran bo Odar

Starring Ulrich Thomsen, Wotan Wilke Möhring, Sebastian Blomberg, Katrin Sass, Burghart Klaussner

Released in the UK on 28 October

I was brought up to assume that the great detectives belong in a heaving and illegible metropolis - whether Sherlock Holmes with his rapier-like rationality cutting through London's fog or The French Connection's Popeye Doyle losing himself as well as his enemy in the streets of New York. Yet the current - and compelling - breed of European detective stories upset my assumptions, without for a moment feeling like Agatha Christie or Margery Allingham. They are largely set far from the metropolis, luxuriating in the proximity of the natural world. Just think of the Italian detective Montalbano, who plies his trade in Sicily; or Wallander, working out of the Swedish port of Ystad. Even The Killing is set in small and townlike Copenhagen.

A new and absorbing film The Silence is based on the novel by the award-winning German writer Jan Costin Wagner, whose detective operates in and around the Finnish city of Turku. He is just as provincial and nature-close as his European counterparts. The film version of Costin Wagner's novel intensifies the porousness of natural and urban life, transferring its action to some unnamed German region where wheatfields and lakes and houses spilling out into the natural world are as much locations for the action as a housing estate.

The crimes of The Silence are brutal enough, as they are in much contemporary European police fiction - the rape and murder of two girls - yet the use of the natural world lends a certain 19th-century air to the film, as to many other European police dramas. The physical landscape becomes the major way of imagining the inner landscapes of grief and trauma that all the characters suffer - including the grief hammered into the minds of the parents whose children have been murdered.

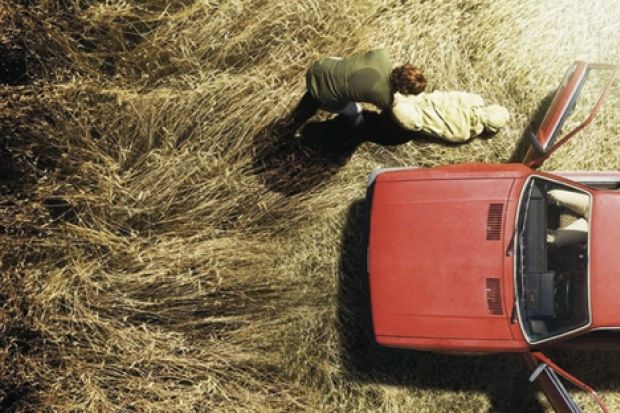

This debut feature, written and directed by German director Baran bo Odar, has at its heart the rape and murder in the mid-1980s of a young girl by a paedophile, on a track across a wheatfield. He dashes out of a car to attack her while another man sits in the passenger seat, apparently traumatised by what is happening. The camera keeps its distance from the attack - and throughout the film, the camera inspects what is going on at a respectful distance rather than entering itself into the action. Close-ups are rare, fast cuts almost non-existent. The film moves between the time of the murder in the 1980s and the near present, exploring a small community that includes the mother of the murdered girl and the murderer, who is the caretaker of a block of flats. The accessory to the rape and murder - the traumatised man in the passenger seat - lives elsewhere, and is married but clearly still sexually compelled by children's bodies, even those of his own family.

An almost identical rape and murder is the catalyst to the film's action. The retired detective on the original case re-enters the scene, believing that there is a connection between the two killings. The mother of the first victim relives the trauma, the distraught parents of the missing girl turn on one another - and the lead detective has to fight his own demons during the investigation - his own grief for his wife who died seven years ago. As the story unravels, it seems as if the murderer has killed the second girl in order to catch the attention of his "friend" who ran away from town after the first murder. The killing of the second girl does bring the men together - but the accomplice cannot come to terms with what has happened or his own desires and commits suicide in the lake where the first girl's body was tipped. As befits a "welfare state" European sensibility, the viewer is asked to understand the perpetrator as well as the victim.

This is very much an ensemble film, with a high-profile cast of European actors including Ulrich Thomsen (lead actor in Thomas Vinterberg's Festen) as the murdering paedophile and Katrin Sass (the sick mother in Good Bye Lenin!) as the long-grieving mother. Yet there is a problem at the heart of the film that has little to do with the quality of individual performances. The Irish poet W.B. Yeats once said that when emotions become intense in naturalist drama, all the characters can do is stare into the fire.

In The Silence, as in some other European police dramas, there is only so much that landscape can do to reflect what is happening in the minds and bodies of human beings. The camera can stare for only so long at a wheatfield across the seasons and the cold, cold lake. In the end, there is kind of emotional blankness at the heart of The Silence, disturbing in a film that is about the consequences of precisely that condition.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login