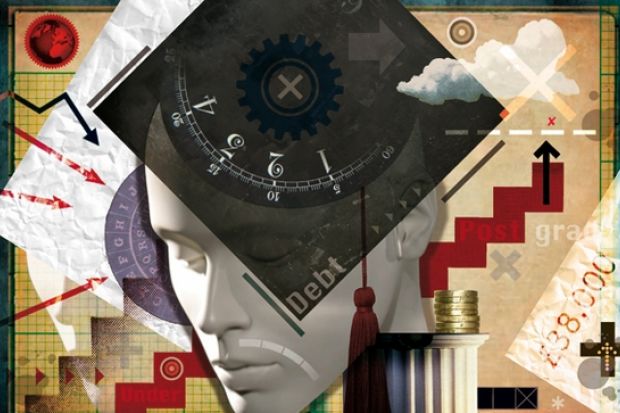

The much delayed White Paper on the future of higher education looks set to finally surface next month. It is a White Paper already defined by the government's decision to cut university teaching funds by 80 per cent and the consequent trebling of tuition fees, effective from 2012-13. As a result, some of the issues that merit debate in the sector are not getting the airing they deserve. One such issue is the future of postgraduate education.

Decisions about how much to charge for postgraduate courses are looming and most independent experts expect fees to rise significantly as the loss of state funding for teaching starts to bite. Some predict that universities will charge the full cost, at least £9,000, to run postgraduate courses such as master's degrees. There are also expectations that funding for supervising postgraduate research will become much harder to secure.

Concerns about both the number of postgraduate places that will be available and whether successful, talented graduates will want to take them up are increasing.

Undergraduates studying traditional three-year degrees at universities charging maximum fees will leave with total debts of almost £40,000. Middle-income graduates - such as health- and social-care workers, police officers and engineers - are set to be hardest hit by the trebling of tuition fees, as they will end up paying back more and for longer. And if they want to enhance their skills through postgraduate study, it looks like they will have to pay substantially higher fees while already struggling with significant levels of debt.

In short, many fear that such levels of graduate debt will deter postgraduate applications. They argue that courses that do not lead directly to highly paid employment but nonetheless are economically and socially valuable, such as the social sciences and the arts, might disappear altogether.

Access to postgraduate study has always been an issue, but notwithstanding Sir Adrian Smith's review of the subject, to date it has received a minimal level of political attention. With numbers of graduates growing both domestically and (crucially) internationally, some in the sector fear that a new educational divide will open up between those with postgraduate qualifications and those without. Social mobility is very much at risk.

Up and down the UK, postgraduate students are involved in groundbreaking research projects that potentially are of huge significance to our country's economic, social and cultural future. The excellence of British research and the benefits it delivers for jobs, tax revenues and UK competitiveness depend in part on a pool of postgraduate students, but higher fees and increasing levels of undergraduate debt are inevitably causing considerable concern as to how deep that pool will be.

With universities also worried about the severity of the impact of the coalition's poorly thought-out overseas student visa changes, and with international interest in British postgraduates increasing, university researchers in the UK can ill-afford a drop in domestic postgraduate applications.

These growing concerns about postgraduate study come as fears increase that the White Paper will not set out a secure financial future for British research. Many universities are worried about the impact of cuts to their research capital budgets, slashed by half last year, with spending on science infrastructure set to drop significantly over the next three years.

Trebling tuition fees was neither fair nor necessary, and there is a chorus of disapproval keen to point out that the government's higher education sums don't even add up. Vince Cable, the coalition business secretary, is sufficiently rattled to have threatened further cuts to university teaching funds and student numbers.

This appears to explain the recent rush of badly presented ideas for last-minute fee reductions and the "plan" for wealthy students to secure university places if they pay their fees up front.

It also accounts for the coalition's interest in expanding the number of US-style for-profit providers of higher education. While we already have successful and effective private providers operating in the UK, figures from the House of Commons Library reveal a far lower level of students completing their degrees with US for-profits, with much higher dropout rates compared with public or not-for-profit institutions.

It is the unfairness of the government's approach as well as its ineptitude that has marked the coalition's handling of universities thus far. The White Paper could have been the moment to put this right. Already it's clear that it will be yet another missed opportunity.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login